- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

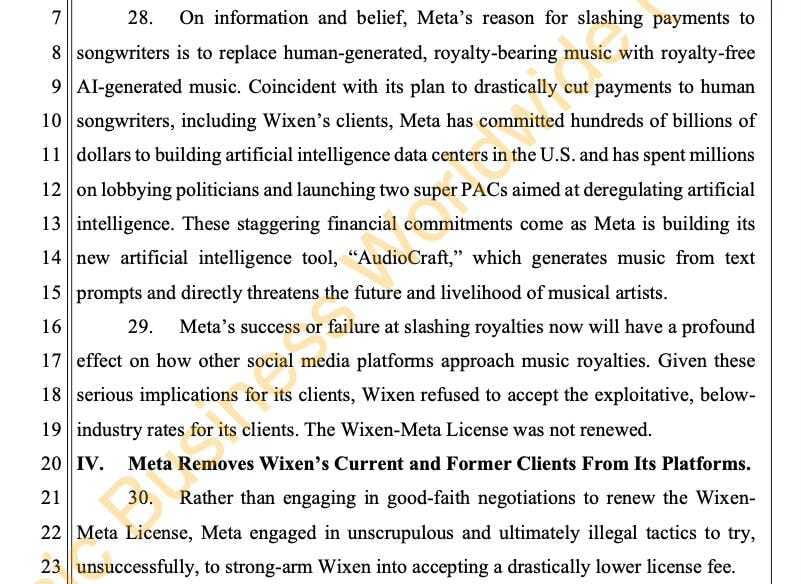

- Wixen v. Meta: Wixen alleges Meta sought to slash license rates to a “small fraction” of historic payments, and—“on information and belief”—the reason is...

Wixen v. Meta: Wixen alleges Meta sought to slash license rates to a “small fraction” of historic payments, and—“on information and belief”—the reason is...

...to replace royalty-bearing human music with royalty-free AI-generated music, pointing to Meta’s AI infrastructure investments and its music-generation tool “AudioCraft.”

Wixen v. Meta: a “music licensing” case wearing an AI costume

by ChatGPT-5.2

Wixen’s complaint against Meta is not primarily a “training-data” lawsuit of the kind that has defined most generative-AI litigation. It is closer to an old-school platform licensing and rights-management dispute: a publisher alleges that (1) its licensed rights expired, (2) Meta kept the songs live and usable inside product features that drive attention and ad revenue, and (3) Meta simultaneously ran a pressure campaign during negotiations by removing music while still licensed and blaming Wixen for the removal. Layered on top are business-tort claims (defamation, trade libel, interference) aimed at the alleged reputational and client-relationship damage caused by Meta’s communications to artists and managers.

The grievances, in plain terms

1) Post-license copyright infringement (direct + contributory).

Wixen alleges its license relationship with Meta dates back to 2018 and that the final license expired “no later than December 10, 2025.”

After expiration, the core accusation is that Meta “reproduced and made the Works available” in the Music Library across Instagram Reels and WhatsApp—enabling thousands of new audiovisual uses and continued availability without authorization or payment.

Legally, Wixen frames this as:

Direct infringement by Meta for reproductions, distribution, public performance, and derivative works via synchronization into user videos.

Contributory infringement because users allegedly created infringing reels, and Meta allegedly “knew or had reason to know” and materially contributed by providing the library, tools, and distribution rails.

2) A “pressure campaign” during negotiations.

Wixen claims that while the license was still active, Meta removed certain Wixen clients’ music anyway, prompting confusion and disruption, then allegedly told clients the removal was Wixen’s fault (e.g., that Wixen was “muting and blocking” the music). Wixen also alleges Meta invented an onerous “relinquishment process” as a pretext to keep former-client catalogs unavailable and to keep attributing the unavailability to Wixen.

3) Defamation, trade libel, and interference with contractual relations.

These claims hinge on Meta allegedly telling “other music publishers, music labels, managers, attorneys, and artists” that music was removed “because of Wixen,” and that reinstatement depended on Wixen “resolv[ing] its issues” or “releas[ing] its claims.” Wixen alleges clients relied on these statements and terminated relationships, and seeks at least $20M on these business-tort theories.

4) The AI “motive” narrative.

This is the rhetorical and strategic framing: Wixen alleges Meta sought to slash license rates to a “small fraction” of historic payments, and—“on information and belief”—the reason is to replace royalty-bearing human music with royalty-free AI-generated music, pointing to Meta’s AI infrastructure investments and its music-generation tool “AudioCraft.”

That AI framing matters politically and reputationally, but it is not the legal center of gravity of the pleaded copyright counts, which are about unlicensed exploitation inside product features after license termination.

The quality of the evidence: unusually “concrete” for an AI-adjacent dispute

Stronger than typical gen-AI cases: the infringement is visible in the product

Many AI training cases start with inference and probabilistic evidence (dataset traces, “regurgitation,” or model-behavior arguments). Here, the complaint’s evidentiary posture is more concrete: Wixen points to product UI and search results showing songs present and usable in Meta’s Music Library after the license ended—e.g., screenshots of “Light My Fire” and “Mr. Roboto,” including an example indicating “300 reels” created using that track/audio.

Additionally, Wixen invokes Meta’s own public Help Center statements acknowledging it must have music rights and uphold agreements with rights holders.

This helps Wixen argue that Meta knows exactly what licensing is required and cannot plausibly present this as an innocent misunderstanding.

Finally, Wixen attaches Exhibit A listing 331 registered works (and signals it believes the total is “well over one thousand”). Registration status is not everything, but it is table stakes for U.S. infringement claims and a major lever for statutory damages.

Where the evidence is thinner: intent, willfulness, and the business-tort layer

Willfulness. Wixen alleges Meta’s conduct is “willful” and seeks maximum statutory damages ($150k/work).

The screenshots and termination date help establishongoing use after notice-worthy events, but “willfulness” often turns on what Meta knew internally, what processes existed, and what happened after specific notifications. That typically requires discovery.

Scale (“thousands of reels”) is pleaded “on information and belief.”

It’s plausible given the platform mechanics, but courts will eventually want hard numbers: logs, catalog availability windows, upload counts, geo-availability, and which rights (composition vs recording) were implicated per use.

Defamation/trade libel/interference are the most vulnerable at the pleadings stage. The complaint asserts categories of recipients and gist of statements, but does not (at least in what’s surfaced in the excerpts) attach the actual emails/messages, name speakers, or provide granular publication details. That may still survive if pleaded with sufficient specificity under applicable standards, but these claims are where Meta has the most room to argue: (a) non-actionable opinion/ambiguity, (b) privilege/justification, (c) lack of “actual malice” (depending on status/standard), and (d) causation problems (artists leaving for independent reasons).

The AI “replace songwriters” theory is also comparatively thin as evidence—it’s pleaded as “on information and belief,” supported by circumstantial context (AI spend, lobbying, AudioCraft).

It’s compelling as narrative, but unless Wixen can tie it to specific conduct (e.g., internal documents about rate cuts to accelerate substitution), it may function more as backdrop than as something the court needs to decide.

How this compares to other AI litigation

1) It’s about distribution and synchronization, not training

Most headline AI cases revolve around whether ingesting copyrighted works to train models is infringement, whether fair use applies, and how to treat outputs. This case is different: it alleges classic exploitation—making music available in a platform library, enabling synchronization into videos, and continuing those uses after a license ended.

If you’re looking for the “AI” in the legal claims, it’s mostly motive and market dynamics, not an element of liability.

2) The evidence is product-native, not model-behavioral

In training cases, plaintiffs often fight on foggy terrain: what was in the training corpus, whether there’s substantial similarity in outputs, whether intermediate copying is actionable, etc. Here, the key evidence is observable availability and use inside Meta’s own product surfaces. That usually makes for a cleaner motion-to-dismiss battlefield.

3) It blends copyright with “platform power” business torts

Most gen-AI copyright suits don’t include defamation/trade libel/interference counts. Wixen does, and that’s telling: the complaint is not only about unpaid rights, but also about how Meta allegedly used its gatekeeping position (music availability on dominant social platforms) to pressure a rights intermediary and destabilize its client relationships.

This isn’t a court being asked to define the frontier of “fair use for AI.” It’s a court being asked whether a platform can (a) keep exploiting works after rights expire and (b) weaponize attribution/blame in negotiations.

Predictions: what’s likely to happen

1) The copyright claims likely survive early motions; the tort claims are more at risk.

Based on how the complaint is structured—license termination date, continued availability allegations, screenshots, and registered works—Wixen’s copyright counts look like they’ll clear the plausibility threshold.

The defamation/trade libel/interference counts are likelier to face narrowing or dismissal unless Wixen can plead and later prove specific communications, speakers, falsity/knowledge, and concrete causation.

2) Expect a hard fight over statutory damages and willfulness.

Wixen’s “$49.65M” number assumes max statutory damages across 331 works and willfulness framing. Courts often award less than the max unless the evidence of intentional misconduct is strong and well-documented.

3) Settlement is structurally likely.

Both sides have incentives:

Wixen wants reinstatement/clarity, money, and reputational repair.

Meta wants to avoid injunctive orders that force process redesign, third-party audits, or operational constraints around music rights management.

A plausible settlement shape: payment for past use + revised licensing terms (or a structured offboarding) + mutual non-disparagement + operational commitments that don’t look like a court-ordered compliance regime.

Advice

For AI developers (and “AI-adjacent” platforms)

Separate AI strategy from rights compliance. If you’re building generative music tools or planning substitution strategies, don’t let that contaminate your licensing posture. The worst look (and sometimes the worst evidence) is when cost-cutting + AI ambition aligns with sloppy rights controls.

Treat “rights offboarding” as a safety-critical system. When licenses end, your catalog removal, caching, UGC linking, and downstream availability must be deterministic and auditable—especially when your UI actively promotes and reuses audio. Wixen is explicitly asking the court to force Meta to implement procedures and even pay a third-party auditor.

Never weaponize attribution messaging. If your support flows or comms tell creators “your publisher did this” when you chose the action (or even when it’s ambiguous), you’re manufacturing tort exposure and turning a commercial dispute into a reputational one.

Assume screenshots will become exhibits. Product UIs are now discovery-ready evidence. Build internal “litigation mode” logging around catalog availability, license windows, takedown triggers, and who approved exceptions.

For future litigants (rights owners / publishers)

Lead with the cleanest claim. Wixen’s best lane is straightforward: post-termination availability + enablement + scale. That is easier to prove than “AI replacement motive.”

Over-collect product evidence early. Time-stamped screen recordings, multiple geos/devices, and repeated checks matter because platforms will argue experiments, caching artifacts, or limited-scope bugs. (Wixen’s reliance on screenshots is the right instinct.)

If you add business torts, bring receipts. Defamation/trade libel/interference can add leverage, but only if you can identify the statements with specificity and tie them to measurable churn and damages.

Ask for operational remedies that change incentives. The most strategically meaningful asks in the prayer for relief aren’t just money—they’re process mandates and auditing. Those remedies move the dispute from “pay us” to “prove you’re clean going forward.”

·

10 JANUARY 2025

·

17 JANUARY 2025

Question for Claude: Please read the article "Exhibits show Meta employees apparently discussing removal of copyright management information from materials from some works in dataset(s)" and tell me what happened and exactly how 'unwise' this is...

·

14 JANUARY 2025

Question 1 of 3 for ChatGPT-4o: Please read the article "Judge Chhabria grants Kadrey, represented by David Boies, leave to amend to file Third Amended Consolidated Complaint. Adds DMCA CMI claim, CA Computer Fraud Act claim. Plus, Kadrey gets to depose Meta about seeding of works via torrents.

·

29 NOVEMBER 2023

Information provided to Claude: “AI Gets a Legal Gift for Thanksgiving” and Order Granting Motion to Dismiss

·

24 DECEMBER 2025

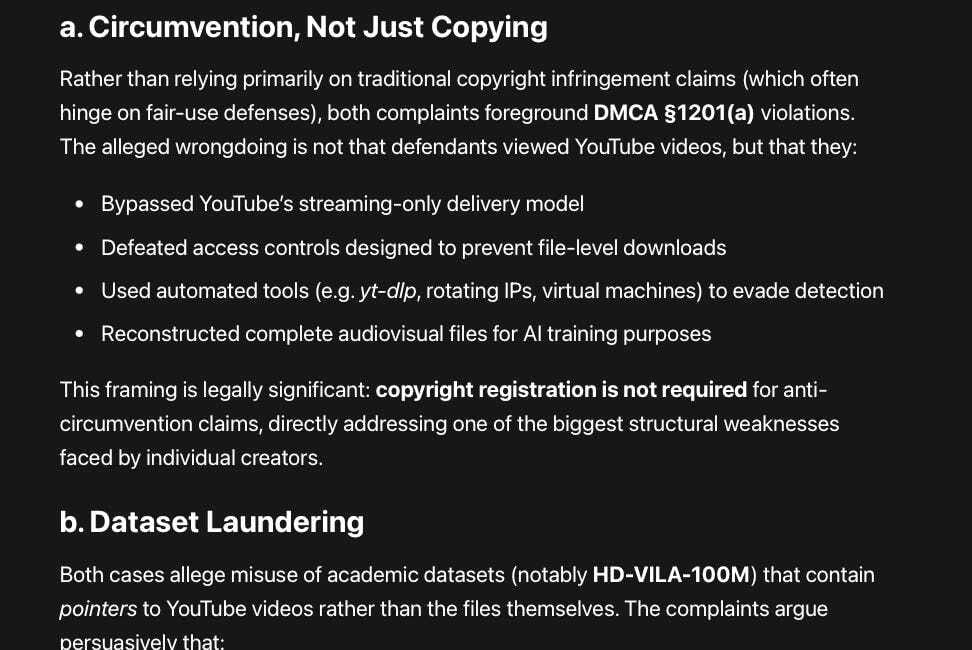

Scraping the Substrate: YouTube Creators v. Generative Video AI

·

12 NOVEMBER 2025

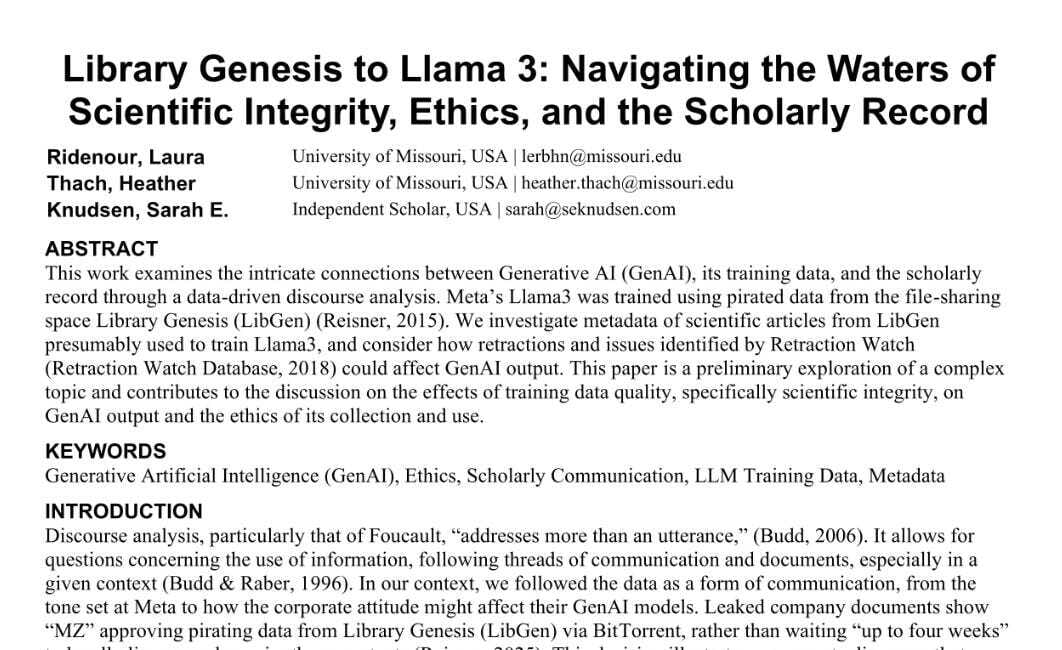

When AI Feeds on Poisoned Knowledge — Lessons from Library Genesis to Llama 3

·

6 AUGUST 2025

Meta’s AI Data Scraping and the Leaked Website List — Implications and Recommendations

·

14 APRIL 2025

Asking AI Services: Please analyze the press release and Amicus Brief of the Association of American Publishers in relation to the META AI Case and tell me whether or not you agree with their views.

·

14 APRIL 2025

Asking AI services: Please analyze the TorrentFreak article “Meta AI ‘Piracy’ Lawsuit: Publishers and Professors Challenge Fair Use Defense” and the associated Amicus Brief from the International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers

·

20 MARCH 2025

Question 1 of 3 for ChatGPT-4o: Please read the article “The Unbelievable Scale of AI’s Pirated-Books Problem - Meta pirated millions of books to train its AI. Search through them here” and tell me what it says. List the most surprising, controversial and valuable statements made.

·

5 MARCH 2025

Asking ChatGPT-4o: Please read the “Report on Pirated Content Used in the Training of Generative AI” and the associated LinkedIn post and tell me what the key messages are and how AI makers should be responding to these issues.

·

7 FEBRUARY 2025

Asking ChatGPT-4o: List every surprising, controversial and valuable detail (for copyright owners) you can find in the newly unsealed emails from META as published by Ars Technica

·

6 NOVEMBER 2023

Question 1 of 6 for ChatGPT-4: Please analyze the Plaintiffs vs META lawsuit and list everything META is being accused of