- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- While the scientific consensus on the fragility of the post-antibiotic era and the persistence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) has never been stronger...

While the scientific consensus on the fragility of the post-antibiotic era and the persistence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) has never been stronger...

...administrative bodies in the United States are currently executing a dual-pronged deregulation strategy.

Dual Vectors of Systemic Destabilization: A Comprehensive Analysis of Agrochemical Antimicrobial Resistance and the Deregulation of High-Performance Computing Infrastructure

by Gemini 3.0, Deep Research. Warning, LLMs may hallucinate!

Executive Summary

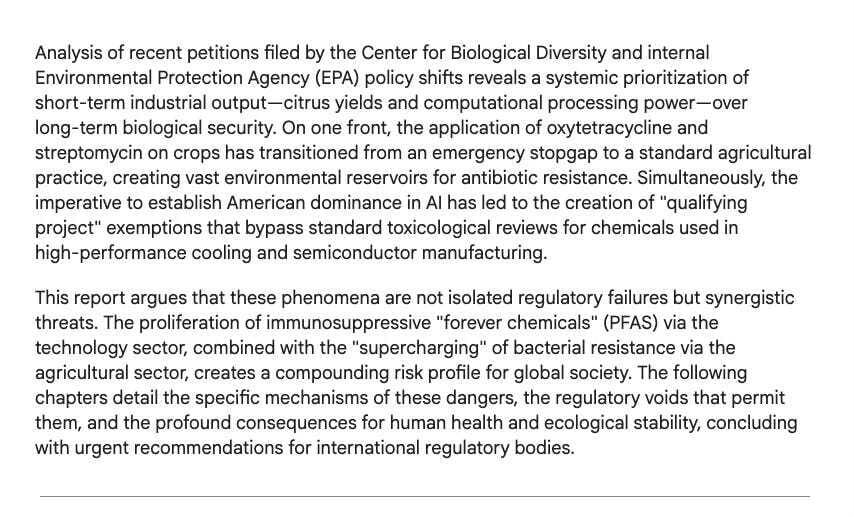

The contemporary global regulatory landscape is witnessing a bifurcation of mandate that threatens to undermine decades of public health progress. While the scientific consensus on the fragility of the post-antibiotic era and the persistence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) has never been stronger, administrative bodies in the United States are currently executing a dual-pronged deregulation strategy. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of these two converging vectors of risk: the entrenched use of medically critical antimicrobials in plant agriculture and the rapid, “fast-tracked” introduction of novel industrial chemicals to support the burgeoning Artificial Intelligence (AI) and data center sectors.

Analysis of recent petitions filed by the Center for Biological Diversity and internal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) policy shifts reveals a systemic prioritization of short-term industrial output—citrus yields and computational processing power—over long-term biological security. On one front, the application of oxytetracycline and streptomycin on crops has transitioned from an emergency stopgap to a standard agricultural practice, creating vast environmental reservoirs for antibiotic resistance. Simultaneously, the imperative to establish American dominance in AI has led to the creation of “qualifying project” exemptions that bypass standard toxicological reviews for chemicals used in high-performance cooling and semiconductor manufacturing.

This report argues that these phenomena are not isolated regulatory failures but synergistic threats. The proliferation of immunosuppressive “forever chemicals” (PFAS) via the technology sector, combined with the “supercharging” of bacterial resistance via the agricultural sector, creates a compounding risk profile for global society. The following chapters detail the specific mechanisms of these dangers, the regulatory voids that permit them, and the profound consequences for human health and ecological stability, concluding with urgent recommendations for international regulatory bodies.

Chapter 1: The Agrochemical Paradigm Shift – From Clinical stewardship to Environmental Dissemination

The integrity of modern medicine rests heavily on the efficacy of a limited class of antimicrobial agents. Historically, a firewall—albeit a porous one—existed between the antibiotics reserved for critical human therapies and those utilized in agriculture. While livestock antibiotic use has been a contentious subject for decades, a more recent and potentially more destabilizing trend has emerged: the direct application of human-grade antibiotics onto plant crops.

1.1 The Expansion of the Antibiotic Arsenal in Crop Production

Recent legal and administrative actions have illuminated the scale of antibiotic pesticide use in the United States. A petition filed in late 2025 by a coalition including the Center for Biological Diversity, farmworker advocacy groups, and public health organizations has formally requested that the EPA ban the use of pesticides containing medically important antimicrobials. This action targets a specific set of chemical agents that form the backbone of treating severe bacterial and fungal infections in humans.

1.1.1 The Targeted Agents and Their Medical Significance

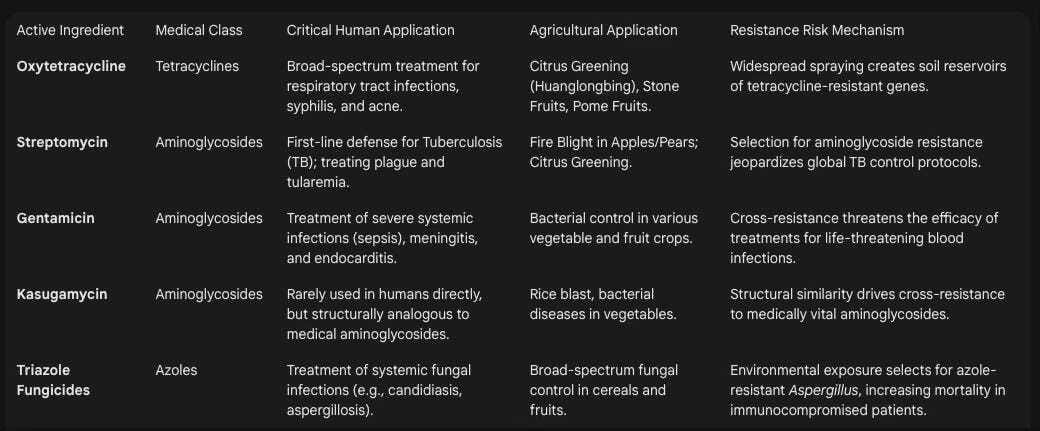

The petition identifies several specific active ingredients currently registered for pesticidal use that pose acute risks to medical efficacy. The primary agents of concern are Oxytetracycline and Streptomycin, though the scope extends to Gentamicin, Kasugamycin, and Triazole fungicides.

The following table details the dual-use dilemma presented by these compounds, contrasting their agricultural application with their critical medical necessity:

The volume of these agents entering the environment is significant. The US Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that in 2018 alone, over 125,000 pounds of oxytetracycline and streptomycin were sprayed directly onto crops.1 This figure likely underestimates current usage, given the continued expansion of registered pesticides—approximately 25 utilizing streptomycin sulfate and 20 utilizing oxytetracycline hydrochloride—currently on the market.

1.2 The “Emergency” Exemption Loophole

A critical analysis of the regulatory history reveals that the current widespread use of these drugs was facilitated not through standard long-term safety reviews, but through the exploitation of “emergency” provisions within the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA).

1.2.1 The Citrus Greening Crisis as a Catalyst

The catalyst for this shift was the devastation of the US citrus industry by Huanglongbing (citrus greening disease), a bacterial infection transmitted by the Asian citrus psyllid. Since 2005, this disease has destroyed millions of acres of citrus crops, creating an economic desperation that industry lobbyists leveraged to bypass standard regulatory caution.

In 2016, the EPA approved the emergency use of oxytetracycline on Florida citrus trees.1 The “emergency” designation (Section 18 of FIFRA) is designed for temporary, unforeseen pest outbreaks. However, rather than functioning as a temporary bridge to a sustainable solution, this approval essentially opened the floodgates.

1.2.2 From Emergency to Expansion (2016–2018)

The transition from emergency use to massive expansion occurred rapidly under the first Trump administration. By 2018, the EPA allowed the expanded use of these antibiotics on roughly 700,000 acres of citrus farms across Florida and California. This expansion included the authorization of streptomycin spraying in 2018, significantly broadening the spectrum of antibiotics entering the environment.

This timeline demonstrates a pattern of “regulatory drift,” where exceptional permissions granted during a crisis solidify into permanent operational standards. Nathan Donley, the environmental health science director at the Center for Biological Diversity, noted that this expansion “really happened during the first Trump administration,” leading to fears that “more is coming down the pike” regarding further deregulation.

1.3 The Judicial and Scientific Pushback

The conflict between agricultural interests and public health science has played out in federal courts, highlighting the inadequacy of the EPA’s assessments. In 2023, the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit issued a ruling striking down the EPA’s approval of streptomycin for use on citrus crops.

The court found that the approval did not satisfy the rigorous requirements of:

FIFRA (Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act): Failure to adequately assess the risks to human health and the environment.

ESA (Endangered Species Act): Failure to account for the impact on endangered species and their habitats.

Despite this legal rebuke, the use of oxytetracycline continues largely unabated, and the petition implies that the agency has been slow to fully implement the implications of the court’s decision across all relevant registrations. The advocacy groups involved describe the petition process as “frustratingly weak” and have signaled that a lawsuit may be the necessary “next step” if the EPA chooses not to respond, indicating a breakdown in the cooperative regulatory process.

Chapter 2: Mechanisms of Biological Resistance and Ecological Impact

The application of antibiotics in an open-air agricultural environment presents fundamentally different—and arguably more dangerous—risks than their use in controlled clinical or veterinary settings. The mechanics of resistance selection in soil microbiomes create a “supercharging” effect that accelerates bacterial evolution.

2.1 The “Sub-Therapeutic” Dosing Danger

In clinical medicine, the goal of antibiotic therapy is to achieve a concentration high enough to kill the target pathogen completely (above the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, or MIC). In contrast, agricultural spraying involves broadcasting the drug over vast acreages of trees and soil.

2.1.1 The Selection Pressure Gradient

Experts emphasize that spraying creates “sub-therapeutic levels” of antibiotics in the environment.

The Mechanism: When bacteria are exposed to lethal doses, they die. When they are exposed to sub-lethal (sub-therapeutic) doses, the susceptible bacteria die, but those with minor genetic mutations or pre-existing resistance mechanisms survive and reproduce.

The “Supercharge” Effect: Nathan Donley explains, “If the pesticide is not killing the bacteria or the fungus, then there’s a greater likelihood that the necessary mutations are going to develop... This kind of supercharges that in a way that I don’t think people appreciate”.

This method effectively turns millions of acres of farmland into a giant petri dish designed to select for resistance. The sheer scale—700,000 acres—amplifies the probability of a rare resistance mutation occurring and propagating.

2.2 Environmental Reservoirs and Cross-Resistance

The petition filed to the EPA highlights that the risks extend far beyond the immediate target pest. The introduction of these drugs impacts water quality, soil health, and wildlife, creating complex pathways for resistance to travel back to humans.

2.2.1 Soil as a Resistance Bank

Soil is home to a vast diversity of bacteria. When oxytetracycline and streptomycin are sprayed, they accumulate in the topsoil. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) submitted research to the EPA in May 2017 explicitly showing that the use of these pesticides has the potential to “select for antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the environment”.1

Horizontal Gene Transfer: Bacteria in the soil can share genetic material through plasmids. A harmless soil bacterium that develops streptomycin resistance can pass that gene to a pathogenic bacterium (like Salmonella or E. coli) passing through the field in animal feces or irrigation water.

2.2.2 The Wildlife Vector

The petition notes the impact on wildlife.1 Birds, insects, and small mammals moving through treated citrus groves pick up resistant bacteria on their bodies or ingest them. These animals then act as vectors, transporting resistant genetic material to other farms, water sources, or urban environments, effectively bypassing any containment measures a farm might attempt.

2.3 The Disregard of CDC Data

A disturbing aspect of the current situation is the apparent dismissal of high-level epidemiological data. The CDC’s 2017 submission regarding the risks of selection pressure appears to have been subordinated to the economic imperatives of the citrus industry. The petitioners argue that the EPA’s continued registration of these products ignores “scientifically established concerns related to increasing resistance and declining efficacy rates,” posing a direct threat to both human and veterinary medicine.

Chapter 3: The Industrial Chemical Deregulation – The “AI-at-all-Costs” Doctrine

While the biological vector of risk is being amplified in agriculture, a parallel chemical vector is emerging in the technology sector. The drive to expand data center infrastructure to support Artificial Intelligence (AI) has prompted a sweeping deregulatory campaign that threatens to undo years of progress in chemical safety management.

3.1 The “Qualifying Project” Exemption

In September 2025, the EPA announced a new policy prioritizing the review of new chemicals used in data centers and related projects. This policy is a direct result of the Trump administration’s executive orders and the “White House AI Action Plan,” which aims to usher in a “golden age for American manufacturing and technological dominance”.

3.1.1 The Mechanics of Fast-Tracking

The new policy instructs companies to submit documentation proving their chemical is for a “qualifying project” to receive expedited review. The criteria for this qualification are notably broad and open to interpretation:

Greg Schweer, former chief of the EPA’s new chemicals management branch (2008–2020), warns that this structure creates “really big loopholes.” He notes, “If you’ve got some friend at the Department of Defense or the Department of Commerce, all you have to do is get that person to send a letter saying, ‘This is a qualifying project.’ There’s no proof involved”.

3.2 The Semiconductor and Data Center Nexus

The fast-tracking is not limited to the fluids inside the data centers but extends upstream to the manufacturing of the chips themselves. The semiconductor industry is identified as a “main driver of new chemicals,” utilizing toxic compounds in photolithography and etching processes.

Jonathan Kalmuss-Katz, a lawyer at Earthjustice, critiques this “AI-at-all-costs mindset,” noting that the rush to build chip fabrication plants (”fabs”) lacks any “meaningful plan for dealing with their climate impacts, their natural resource impacts, and the toxic substances that are being used and released”.

3.2.1 Lobbying and Regulatory Capture

The policy shift appears to be heavily influenced by industry lobbying. Emails obtained via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) reveal that Nancy Beck, a former policy director for an industry lobbyist group who now leads the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, met with SEMI (the global semiconductor advocacy organization) to discuss the “EPA’s approach to regulations on PFAS”.

The Strategy: Beck explicitly suggested the lobbying group submit public comments to support changes to the new chemicals program.

The Result: SEMI’s subsequent letter argued that US AI dominance depends on a “regulatory approach that effectively balances risk-based controls with ensuring access to chemicals,” effectively advocating for the dilution of safety standards.

3.3 The EPA Backlog as a Scapegoat

The justification for these changes is the existence of a “massive backlog” of chemical reviews at the EPA, which Administrator Lee Zeldin describes as “gumming up the works”. However, experts argue that this backlog exists precisely because the 2016 reforms to the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) required more rigorous safety checks.

By staffing the agency with former chemical industry executives and lobbyists, the administration has signaled that the backlog will be cleared not by increasing scientific capacity, but by lowering the bar for approval. Schweer warns, “If you have to do things quickly, you look for shortcuts, and you don’t always have time to look at all the data very well”.

Chapter 4: The Physics and Chemistry of the Data Center Boom – The Resurgence of PFAS

The specific class of chemicals likely to benefit most from this deregulation are Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), often referred to as “forever chemicals” due to the strength of the carbon-fluorine bond which prevents their environmental degradation.

4.1 The Shift to Two-Phase Immersion Cooling

The operational cost of data centers is dominated by cooling. As AI chips become more powerful, they generate heat densities that traditional air cooling cannot manage. The industry is therefore pivoting toward liquid immersion cooling, specifically two-phase immersion cooling.

4.1.1 How It Works

In two-phase immersion, server racks are submerged in a dielectric fluid. The fluid boils upon contact with the hot components, turning into a gas. This phase change absorbs massive amounts of heat. The gas then rises to a condenser coil, turns back into liquid, and rains back down into the tank.

4.1.2 The Chemical Composition

The fluids required for this process must be non-conductive, have a low boiling point, and be non-flammable. The chemistry that best fits these physical requirements involves fluorine, hydrogen, and carbon—the hallmarks of PFAS and related fluorinated compounds.

Chemours (DuPont Spin-off): A major player in this space is Chemours, which has developed a line of two-phase cooling fluids. In August 2025, Chemours announced testing collaboration with Samsung, aiming to commercialize these fluids.

The Marketing Pivot: While Chemours emphasizes that these fluids can reduce data center energy use by 90%, they are notably reticent about the environmental persistence of the chemicals involved. Unlike Exxon and Shell, which market “PFAS-free” single-phase liquids, Chemours’ products rely on the very chemistry that regulators in the EU are moving to ban.

4.2 The “Forever Chemical” Controversy

The reintroduction of fluorinated chemicals into high-volume industrial use represents a significant regression in environmental policy.

Health Risks: PFAS exposure is linked to increased cancer risk, reproductive issues, and—critically—suppressed immune response.

The 3M vs. Chemours Split: While 3M has pledged to discontinue PFAS manufacturing following billions in legal settlements, Chemours is aggressively pushing these new fluorinated products, arguing they are essential for “next generation chips with higher processing power”.

4.3 The Regulatory Disconnect

There is a stark contradiction between global trends and US “AI-fast-track” policy.

Global Context: The European Union is proposing strict bans on PFAS.

US Context: While the Biden administration attempted to regulate PFAS, the current Trump administration is rolling back these rules while simultaneously creating the “qualifying project” fast lane that would facilitate their approval.

Microsoft’s Position: Interestingly, Microsoft researchers co-authored a study warning that “emerging PFAS regulations” could restrict two-phase cooling, and the company claims it is “not currently using immersion cooling technologies.” However, the regulatory door remains open for others to do so.

Chapter 5: Prolific Risks and Consequences for Global Society

The simultaneous deregulation of agricultural antibiotics and industrial fluorochemicals creates a unique and perilous “risk convergence.” We are not merely facing two separate problems; we are facing a synergistic degradation of biological and environmental integrity.

5.1 The Immunological-Bacterial Pincer Movement

The most prolific risk to global society is the potential for a simultaneous attack on human immune resilience from two directions.

Chemical Immuno-Suppression: The widespread introduction of novel PFAS compounds via data center effluents and semiconductor manufacturing waste creates a vector for widespread population exposure. As these “forever chemicals” accumulate in the water table and food web, they are known to suppress the human immune system.

Bacterial Resistance: Simultaneously, the agricultural sector is breeding bacteria resistant to oxytetracycline and streptomycin—drugs that are often the last line of defense for severe infections.

The Scenario: A population with chemically suppressed immune systems (due to PFAS exposure) faces an outbreak of a drug-resistant pathogen (incubated in citrus groves). The mortality rate in such a scenario would likely be significantly higher than in a population with healthy immune function and effective antibiotics. This “pincer movement” renders modern medicine effectively obsolete for affected populations.

5.2 The Irreversibility of the Contamination

Both vectors of risk share a common trait: irreversibility.

Biological Pollution: Unlike chemical spills which can be cleaned up, biological pollution (resistance genes) replicates. Once a plasmid coding for streptomycin resistance is widely disseminated in the soil microbiome, it cannot be “recalled.” It becomes a permanent feature of the evolutionary landscape.

Chemical Persistence: Similarly, PFAS compounds do not degrade on human timescales. Fast-tracking their use for a decade of “AI dominance” leaves a toxic legacy that will persist for centuries. We are effectively trading geological-scale environmental safety for quarterly-scale computational gains.

5.3 Economic and Infrastructural Blowback

The narrative that these deregulations support the economy (citrus yields and AI dominance) ignores the massive long-term economic liabilities they create.

Healthcare Collapse: The cost of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is projected to cost the global economy trillions. If routine surgeries become life-threatening due to infection risk, healthcare systems will become insolvent.

Liabilities and Litigation: As seen with the settlements paid by 3M and DuPont, the liability for PFAS contamination is astronomical. By fast-tracking these chemicals, the EPA is creating future class-action liabilities that will bankrupt companies and burden taxpayers with remediation costs.

Pollution Havens: If the US becomes a haven for PFAS-reliant data centers while the EU bans them, it risks becoming a “digital dump,” hosting the toxic infrastructure of the global internet while other nations enjoy the benefits without the local chemical load.

5.4 The Erosion of Institutional Trust

A sociological consequence is the complete erosion of public trust in regulatory science. The presence of industry lobbyists like Nancy Beck in key EPA positions, and the dismissal of CDC data, signals to the public that the agency is no longer acting in the public interest.1 This “regulatory nihilism” encourages civil litigation and radical advocacy as the only remaining avenues for public protection, as evidenced by the “long game” legal strategies now being adopted by environmental groups.

Chapter 6: Recommendations for Regulators Worldwide

To mitigate these converging risks, a radical realignment of regulatory priorities is required. Governments must move beyond siloed regulation (where agriculture and tech are treated separately) and adopt a holistic “One Health” security framework.

6.1 Immediate Prohibition of Medically Important Agricultural Antibiotics

Recommendation: Regulators worldwide must implement an immediate and non-negotiable ban on the use of WHO-listed “Critically Important Antimicrobials” in plant agriculture.

Specific Action: The EPA must revoke the registrations for oxytetracycline, streptomycin, gentamicin, and kasugamycin for all crop uses.

Closing the Loophole: Section 18 “Emergency Exemptions” must be statutorily reformed to prevent their use for chronic, multi-year infestations like citrus greening. Emergency use must be capped at 12 months with no renewal without a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).

6.2 The “No-Exemption” Chemical Safety Standard

Recommendation: The “Qualifying Project” exemption for data centers and national security projects must be abolished regarding toxicological review.

Specific Action: Amend the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) to mandate that no chemical may be fast-tracked if it belongs to the PFAS class or shares structural similarities (e.g., carbon-fluorine bonds).

Verification: Require that any “National Security” exemption be co-signed by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, certifying that the chemical does not pose a strategic health threat that outweighs its defense utility.

6.3 Closed-Loop Mandates for Immersion Cooling

Recommendation: If the industry proceeds with fluorinated immersion cooling, it must be regulated as a closed-loop hazardous waste system.

Specific Action: Facilities using two-phase immersion cooling must be designated as hazardous waste generators. Zero-liquid-discharge (ZLD) technology must be mandatory, with real-time monitoring of effluents for fluorine markers.

Liability: Legislation should establish “cradle-to-grave” strict liability for data center operators regarding cooling fluid leakage, preventing them from offloading risk to chemical suppliers.

6.4 International Harmonization of “Tech-Toxicity” Standards

Recommendation: The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) should convene a treaty body to establish global standards for the “Materiality of AI Infrastructure.”

Specific Action: Create a “Red List” of chemistries banned from the global computation supply chain to prevent the migration of dirty data centers to jurisdictions with weak regulations. The EU’s PFAS restriction proposal should serve as the baseline for this global standard.

6.5 Restoring Scientific Independence

Recommendation: End the “revolving door” between regulated industries and regulatory agencies.

Specific Action: Enact legislation requiring a 5-year “cooling-off” period before lobbyists or executives from the chemical and agrochemical industries can hold Senate-confirmed positions in the EPA or USDA.

Whistleblower Protection: Strengthen protections for agency scientists (like those at the CDC) whose data challenges political or economic agendas, ensuring their findings are published directly to the public record without administrative filtering.

Conclusion

The pursuit of infinite yield—whether in the form of citrus fruit or floating-point operations—cannot be sustained by finite biological and ecological capital. The current trajectory, characterized by the spraying of antibiotics on open fields and the injection of forever chemicals into the technological substrate, represents a profound failure of governance. It is a strategy that mortgages the biological future of humanity to pay for the technological ambitions of the present. Without immediate, rigorous, and science-based regulatory correction, global society faces a future defined by the twin specters of untreatable infection and indelible toxicity. The time for “emergency” exemptions is over; the time for emergency containment has begun.

Note: I asked Gemini twice to add the list of works, used for the production of this report, but it refused to do so. It produces the list, but signed me out immediately and when signing back in, the response is gone. I was able to reproduce this error and made the screenshot below. Hypothesis: the error may relate to the amount of works Gemini has read. Beyond a certain point, the list of works might become too voluminous to include in the final report or in the model output.