- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- This report begins where conventional analysis ends: at the point of systemic institutional failure. It addresses the exigent circumstances that arise when the established tools...

This report begins where conventional analysis ends: at the point of systemic institutional failure. It addresses the exigent circumstances that arise when the established tools...

...of democratic governance and civic action have been tried, tested, and ultimately proven insufficient to halt the slide into authoritarianism.

The Final Recourse: A Strategic Framework for Societal Resistance to Authoritarian Rule

by Gemini 2.5 Pro, Deep Research. Warning! LLMs may hallucinate!

Introduction: When All Else Fails

This report begins where conventional analysis ends: at the point of systemic institutional failure. It addresses the exigent circumstances that arise when the established tools of democratic governance and civic action have been tried, tested, and ultimately proven insufficient to halt the slide into authoritarianism. The scenario under examination is one where judicial review has been systematically subverted, rendered impotent by a dominant executive 1 ; where legislative oversight has been neutered, its inquiries ignored and its powers of compulsion defied 4 ; where the ultimate constitutional failsafe of impeachment has been rendered politically impossible or has failed to secure its objective 7 ; and where initial forms of public protest have been suppressed, co-opted, or dismissed without effect.10 This is the grim culmination of what political scientists term "democratic backsliding" or "executive aggrandizement"—the incremental dismantling of democracy by elected leaders through a steady centralization of power and the undercutting of all checks and balances.11

When a state's formal mechanisms of accountability collapse, the locus of power and the responsibility for democratic preservation shift decisively from institutions to society itself. The strategic imperative must therefore pivot from a framework of democratic defense, which operates within the established constitutional order, to one of democratic recovery and liberation, which must operate outside of and in opposition to a captured state apparatus. This report argues that the most effective path forward in such a dire context is not through spontaneous acts of rage or a recourse to violent insurrection—strategies that historically have a low probability of success and a high probability of leading to further devastation and enduring instability. Instead, the evidence-based and strategically superior alternative is a disciplined, systematic, and sustained campaign of nonviolent civil resistance.

The failure of institutional checks is not merely a political or constitutional crisis; it represents a fundamental rupture of the social contract. An authoritarian regime, by systematically dismantling the mechanisms of consent, accountability, and the rule of law, voids its own legitimacy. This process transforms the nature of subsequent societal action. What might have once been considered "protest" against a legitimate government becomes, in this new context, a legitimate "reclamation" of sovereignty by the people. The theoretical underpinnings for this shift are found in the foundational works of social contract theory. Political philosophers such as John Locke argued that governments are instituted by the consent of the governed for the explicit purpose of protecting their natural rights to life, liberty, and property.12 When a government becomes destructive of these ends, engaging in a "long train of abuses" that evinces a design to reduce the people under absolute despotism, it breaks the foundational contract. At that point, Locke contends, power "devolve[s] into the hands of those that gave it, who may place it anew where they shall think best for their safety and security".15 The scenario of total institutional failure, therefore, is the literal embodiment of the conditions that justify the dissolution of government and the reassertion of popular sovereignty. This philosophical framework is critical, as it provides the moral and theoretical justification for the extraordinary measures outlined in this report. It reframes the ensuing struggle not as an illegal rebellion against lawful authority, but as a righteous and necessary act of societal self-preservation aimed at reconstituting a legitimate political order.

This report will proceed by first establishing the philosophical foundations for resistance. It will then present the compelling empirical evidence for the strategic superiority of nonviolent methods. Following this, it will detail a comprehensive framework for action, centered on the deconstruction of the regime's "pillars of support." This includes a tactical guide to the methods of nonviolent noncooperation, specific strategies for winning over key societal sectors—most critically the security forces and economic elites—and an analysis of the role the international community can play. Finally, the report will address the crucial post-uprising phase, outlining a roadmap for transitioning from resistance to resilient, durable democratic governance.

Before a society can embark on the perilous path of resistance against an entrenched authoritarian regime, it must establish a firm intellectual and moral foundation for its actions. This foundation serves not only to justify the struggle to its participants and the international community but also to define the ultimate goals of the movement: the restoration of a government based on consent, the rule of law, and the protection of fundamental rights. The intellectual tradition of the social contract, particularly as articulated by John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and later refined into a call for individual action by Henry David Thoreau, provides this essential framework.

The Lockean Right of Revolution

The cornerstone of the right to resist tyranny in the Western political tradition is John Locke's Second Treatise of Government.14 Locke's theory begins with a hypothetical "state of nature," a condition of perfect freedom and equality in which individuals are governed only by the law of nature, which dictates that no one ought to harm another in their life, health, liberty, or possessions.17 To escape the insecurities and inconveniences of this state, where every individual is the judge in their own case, people voluntarily enter into a social contract. They agree to form a political community and surrender some of their natural freedoms—specifically the power to execute the law of nature themselves—to a common government.12

Crucially, this grant of authority is conditional. The government's legitimacy is derived entirely from the "consent of the governed" and is limited by its purpose: the preservation of the people's lives, liberties, and property.14 When a government violates this trust and acts against the interests of the people it was created to protect, it ceases to be legitimate. Locke argues that if a ruler or legislature engages in a "long train of abuses, prevarications and artifices, all tending the same way," it becomes manifest that their design is to establish absolute tyranny.15 In such a scenario, the government has effectively declared a state of war against its own people. By breaking the social contract, the government forfeits its authority, and the power it once held reverts to the community.15 At this point, the people have not only the right but a profound duty to resist that government and to "provide for their own safety and security, which is the end for which they are in society".15 This Lockean framework provides the ultimate justification for resistance when all institutional channels for redress have been closed. It establishes that the act of overthrowing a tyrannical regime is not an act of illegal insurrection but a fundamental act of societal self-defense and the re-establishment of legitimate political order.21

Rousseau and the General Will

The work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, particularly in The Social Contract, adds another layer to this philosophical justification.22 Rousseau introduced the concept of the "general will," which represents the collective interest of the community as a whole, aimed at the common good.13 For Rousseau, a legitimate state is one where the laws and actions of the government are an expression of this general will. Sovereignty, in his view, resides not with the government but with the people, and the government is merely an agent tasked with executing their collective will.22

An authoritarian regime, by its very nature, subverts the general will. It replaces the common good with the private interests of a single ruler or a small elite.23 Decisions are made not through public deliberation and consent but by arbitrary decree. The regime systematically dismantles the institutions that allow the general will to be formed and expressed, such as free elections, independent media, and civil society organizations.11 In this context, resistance can be powerfully framed as an effort to restore popular sovereignty. It is not merely a reaction against oppression but a proactive struggle to create a state that is a true reflection of the people's collective aspirations for a just and equitable society. When a government attempts to subvert the general will, Rousseau argues, the citizens have the right to replace it.22

Thoreau and the Mandate of Conscience

While Locke and Rousseau provide the justification for collective, societal-level revolution, Henry David Thoreau's essay "Civil Disobedience" provides the moral imperative for individual action.24 Writing in protest against slavery and the Mexican-American War, Thoreau argues that an individual's highest obligation is not to the law, but to their own conscience.25 He famously asks, "Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislator?" His answer is a resounding no. He contends that an unthinking respect for law leads people to become agents of injustice, like soldiers marching off to an unjust war.24

When the state becomes a perpetrator of profound injustice, Thoreau argues, the truly just person must withdraw their allegiance and refuse to cooperate with it. "Under a government which imprisons any unjustly," he declares, "the true place for a just man is also a prison".26 This is not a call for violent overthrow but for a radical act of non-cooperation. By refusing to pay taxes, for example, the individual refuses to provide their material support to the machinery of injustice.26 This act of "washing his hands" of the government is a moral necessity for the individual, regardless of whether it immediately succeeds in reforming the state.24

The philosophical progression from Locke to Thoreau is crucial for formulating a modern resistance strategy. It demonstrates a conceptual shift from a collective, last-resort right to revolution to an individual, immediate duty of non-cooperation. A successful contemporary movement must synthesize both of these powerful ideas. The grand, Lockean framework provides the overarching legitimacy for the movement's ultimate goal: the dissolution of the tyrannical regime and the establishment of a new government. It answers the question, "Why are we fighting?" with a clear, historically resonant appeal to the principles of popular sovereignty and natural rights.

Simultaneously, the Thoreauvian ethos provides the moral engine for the daily, individual acts of resistance that are the tactical lifeblood of the campaign. It answers the question, "What must I do today?" by empowering each citizen to act on their conscience and refuse complicity in the regime's specific injustices. This could mean a civil servant "misplacing" an order for political arrests, a journalist refusing to print state propaganda, or a citizen refusing to pay a tax that funds the security apparatus. This dual approach dramatically broadens the movement's appeal. It allows individuals to participate at varying levels of risk and commitment, from small acts of disguised disobedience to open defiance, all contributing to the same strategic objective of undermining the regime's authority. The Lockean goal gives the movement its direction, while the Thoreauvian duty gives it its power.

Section II: The Strategic Imperative: Why Civil Resistance Works

While philosophical principles provide the moral justification for resistance, the choice of strategy and tactics must be grounded in a pragmatic assessment of what is most likely to succeed. A common assumption is that a regime that has consolidated power and controls the instruments of violence can only be dislodged by a countervailing violent force. However, a vast body of empirical evidence compiled over the last century overwhelmingly refutes this notion. The data demonstrates that nonviolent civil resistance is not only a morally preferable alternative but also a strategically superior one.

The Empirical Evidence

The most comprehensive and influential research in this field was conducted by political scientists Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan. In their seminal book, Why Civil Resistance Works, they systematically analyzed 323 major violent and nonviolent campaigns aimed at overthrowing a government or achieving territorial liberation between 1900 and 2006.28 Their central finding is a paradigm-shifting revelation for the study of political conflict: campaigns of nonviolent resistance were more than twice as effective as their violent counterparts in achieving their stated goals.31 Specifically, 53% of nonviolent campaigns succeeded, compared to only 26% of violent insurgencies.32 This statistical advantage holds true across different historical periods and geographical contexts, and, critically, it persists even when movements face highly repressive and authoritarian opponents.29 More recent data extending through 2019 confirms this trend, solidifying the conclusion that, on strategic grounds, nonviolent struggle is the more effective choice.32

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of Violent vs. Nonviolent Campaigns (1900-2006)

Source: Adapted from data presented in Chenoweth, E., & Stephan, M. J. (2011). Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. 29

The "Participation Advantage": The Causal Mechanism of Success

The superior success rate of nonviolent resistance is not a matter of chance; it is rooted in a core strategic dynamic that Chenoweth and Stephan term the "participation advantage".33 The fundamental reason nonviolence works better is its ability to attract significantly larger and more diverse participation from the general population.

Violent insurgency has high barriers to entry. It requires physical fitness, a willingness to kill, and access to weapons, which inherently limits participation to a relatively small, demographically narrow segment of society, typically young men.30 In contrast, nonviolent resistance has dramatically lower moral and physical barriers. The vast repertoire of nonviolent tactics—from boycotts and strikes to symbolic protests and stay-at-homes—allows for the active participation of women, the elderly, children, people with disabilities, professionals, religious figures, and others who would be unable or unwilling to join an armed rebellion.36

This capacity for mass mobilization is the key to success. Research has identified what is often called the "3.5% Rule," which posits that no government has been able to withstand a challenge from 3.5% of its population engaged in sustained nonviolent resistance.39 While this is a correlational finding, not an iron law, it illustrates the power of numbers. Large-scale participation enhances a movement's resilience, increases its capacity for tactical innovation, and creates widespread social, economic, and political disruption that makes the status quo untenable for the regime.29

The success of nonviolent resistance is ultimately a function of its ability to impose diverse and simultaneous costs on a regime across multiple societal domains, whereas violent resistance tends to consolidate the conflict into a single domain—the military—where the state almost always possesses an overwhelming advantage. An armed insurgency directly challenges the state's monopoly on violence, which is its area of greatest strength. This framing justifies a purely military and security-based response, which serves to unify the regime's coercive apparatus and often rallies a fearful population around the flag.41

Nonviolent resistance, by contrast, creates a multi-front crisis that the regime cannot easily counter with a single tool. A general strike imposes severe economic costs. Widespread bureaucratic non-cooperation imposes paralyzing administrative costs. Mass protests and the creation of parallel institutions impose profound legitimacy costs. This diversification of the conflict arena forces the regime to fight on terrain where its primary weapons are less effective and often counterproductive. The use of brutal violence against unarmed civilians, for instance, can backfire spectacularly—a phenomenon Gene Sharp termed "political jiu-jitsu"—by shocking the public, eroding the regime's domestic and international legitimacy, and, most importantly, triggering loyalty shifts and defections within the regime's own pillars of support.41

Long-Term Democratic Outcomes

The strategic benefits of nonviolence extend far beyond the immediate goal of regime change. The methods used during the struggle have a profound impact on the nature of the political order that follows. Research has shown that countries where authoritarian regimes are removed through nonviolent campaigns are significantly more likely to become durable democracies and are far less likely to descend into civil war in the aftermath. One study found that countries with nonviolent transitions were approximately ten times more likely to transition to democracy within a five-year period compared to countries where transitions occurred through violence.28

This is because the very process of a mass nonviolent campaign builds the foundations for a democratic society. It fosters broad-based coalitions, develops leadership skills throughout civil society, creates networks of trust and cooperation, and habituates a large segment of the population to political participation and civic engagement.44 In contrast, violent transitions tend to concentrate power in the hands of a small, armed elite, creating a new militarized authority that is often just as repressive as the one it replaced and perpetuating cycles of violence.32 Therefore, the choice of nonviolent resistance is not merely a tactical decision for the present, but a strategic investment in a more peaceful and democratic future.

Section III: Deconstructing Tyranny: Targeting the Pillars of Support

A successful campaign of civil resistance requires more than just mass mobilization; it demands a sophisticated strategic framework that guides its actions. The most influential and widely adopted framework for this purpose was developed by the scholar Gene Sharp, whose work is grounded in a fundamental re-conceptualization of political power.16

Gene Sharp's Theory of Power

The conventional view of power is monolithic: it sees power as something inherent in a ruler, a quality they possess like a scepter or a crown, which emanates downwards to control the populace. Sharp's crucial insight, drawing on a long line of political thought, is that this view is incorrect. Power is not monolithic; it is relational and pluralistic. A ruler's power is not intrinsic but is granted to them by the consent, obedience, and cooperation of the people they rule.41 As Sharp argues, "Obedience is at the heart of political power".41 Even the most ruthless dictator requires the active cooperation of a vast network of individuals and institutions to carry out their will. Without soldiers to enforce decrees, bureaucrats to administer the state, workers to run the economy, and a populace to provide at least passive acquiescence, a ruler is powerless.47

This understanding of power fundamentally alters the strategic logic of resistance. If a ruler's power depends on the cooperation of the governed, then that power can be severed by the systematic and widespread withdrawal of that cooperation.41 The objective of a nonviolent movement is not to defeat the regime in a head-on confrontation but to cause it to disintegrate from within by persuading its sources of power to stop cooperating.

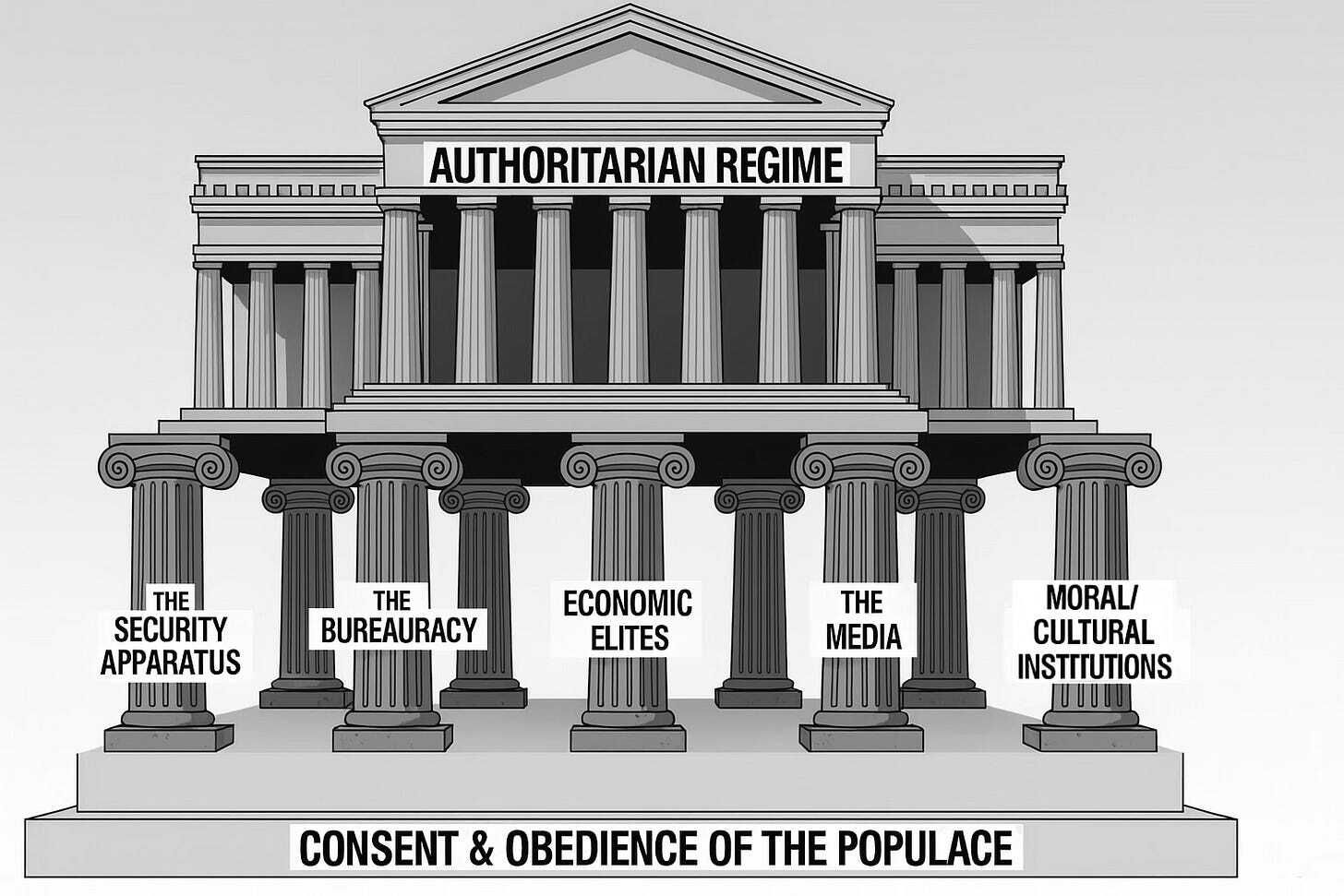

Identifying the Pillars

The power that flows from the populace to the ruler is not amorphous; it is channeled through specific organizations and institutions that function as "pillars of support" for the regime.47 These pillars are the institutional bedrock that upholds the ruler's authority. While the specific configuration of these pillars varies by country, they can be categorized into several universal types:

The Security Apparatus: This is the regime's coercive arm, including the military, national and local police forces, intelligence agencies, and paramilitary groups. Their loyalty is essential for repressing dissent.

The Bureaucracy: This pillar comprises the civil service, the judiciary, and all public administrators who manage the day-to-day functions of the state. Their cooperation is necessary for the state to implement policy and provide services.

Economic Elites: This includes private business leaders, financiers, managers of state-owned enterprises, and powerful trade unions. Their role in generating wealth and managing the economy is vital for the regime's financial stability and its ability to reward key supporters.

Moral/Cultural Institutions: This pillar consists of religious bodies, the educational system, and prominent cultural figures. These institutions provide the regime with legitimacy and shape the social norms and values that encourage obedience.

The Media: This includes both state-controlled media, which functions as a propaganda arm, and co-opted or intimidated private media outlets. Their role is to control the flow of information and shape the public narrative.

The General Public: While the source of all power, the broader population often functions as a pillar through its passive acquiescence and compliance with the regime's demands.

Figure 1: Pillars of Support for an Authoritarian Regime

The Strategic Goal: Systemic Disintegration

The overarching strategic goal of a nonviolent campaign, guided by this framework, is to achieve the systemic disintegration of the dictatorship.16 This is accomplished by systematically targeting each pillar of support with specific tactics designed to erode its loyalty and compel it to withdraw its cooperation from the regime.47 The aim is to make the country ungovernable for the existing rulers, thereby creating a power vacuum that the democratic movement is prepared to fill.

This analytical model reveals a crucial strategic insight: the primary audience for a resistance movement's actions is not the dictator, but the individuals and groups that constitute the pillars. A common error in many protest movements is to direct all messaging and confrontational action at the head of the regime, demanding that they resign or change their policies.10 This approach is often futile, as the ruler is typically the least persuadable actor and the most invested in maintaining the status quo.

Continue reading here (due to post length constraints): https://p4sc4l.substack.com/p/this-report-begins-where-conventional