- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- This report aims to provide a detailed analysis of Argentina's complex relationship with Nazi fugitives in the post-World War II era.

This report aims to provide a detailed analysis of Argentina's complex relationship with Nazi fugitives in the post-World War II era.

In 2025, Argentina’s decision to make public nearly 1,850 documents—including passport applications, police reports, and intelligence bulletins—has reignited historical debates.

Argentina's Post-War Role: Nazi Fugitives, State Complicity, and Historical Reckoning

by Gemini Advanced, Deep Research with 2.5 Pro and revised by ChatGPT-4o. Warning, LLMs may hallucinate!

I. Introduction: Argentina, Nazism, and the Shadows of Post-War History

A. The Persistent Legacy of Sanctuary

Following the Second World War, Argentina emerged not just as a refuge for displaced Europeans but as a calculated sanctuary for some of the most notorious Nazi fugitives. Declassified Argentine intelligence and police files confirm that individuals such as Adolf Eichmann, Josef Mengele, and Walter Kutschmann entered and lived in Argentina with minimal interference from the authorities. These revelations, once fragmented or speculative, are now corroborated through the Argentine government's own surveillance, immigration, and identity records.

In 2025, Argentina’s decision to make public nearly 1,850 documents—including passport applications, police reports, and intelligence bulletins—has reignited historical debates. These documents, many under presidential decree 232/1992, offer unfiltered insight into the systematic operations that allowed Nazi war criminals to settle, thrive, and even conduct business in Argentina.

B. Report Objectives and Scope

Understanding the intricacies of Argentina's post-war policies and actions necessitates rigorous examination of historical records. The Archivo General de la Nación (AGN), Argentina's national archive, holds crucial documentation concerning Nazism and the arrival of fugitives.2 This report re-evaluates Argentina’s role in sheltering Nazi fugitives by integrating newly available primary source material from the Archivo General de la Nación. In doing so, it examines the intentional strategies behind Argentina’s ratline networks, the state's complicity under the Perón administration, and the evolving national stance that culminated in limited cooperation with extradition requests decades later.

This report aims to provide a detailed analysis of Argentina's complex relationship with Nazi fugitives in the post-World War II era, drawing exclusively upon the provided research materials. It will explore the historical context of Argentina's wartime neutrality and the political climate that enabled the influx of Nazis. The analysis will delve into the active role of the Perón administration in facilitating escape through organized "ratlines," the mechanisms and networks involved, and the motivations behind these policies. Furthermore, it will examine the lives and fates of prominent fugitives within Argentina, the evolution of the state's approach—from complicity and impunity to investigation and eventual extradition—and the crucial role of archival evidence and declassification efforts in confronting this history. Finally, the report will consider the impact of international relations and pressure on Argentina's shifting policies over time.

II. Wartime Ambiguity and the Post-War Political Landscape

A. Argentina's WWII Neutrality

Argentina's stance during World War II was characterized by a prolonged period of neutrality, maintained until the conflict's final stages despite significant pressure from the United States to align with the Allied powers.18 This neutrality, formally ending only with a severing of relations with the Axis in January 1944 and a declaration of war in March 1945, was perceived by Washington not as impartiality but as a policy indicative of pro-Axis sympathies.18 The late timing of Argentina's entry into the war, just a month before Germany's final collapse, was viewed by some observers, including within the Perón government itself, as a strategic maneuver undertaken primarily due to overwhelming Allied pressure and the inevitability of an Axis defeat.21

The roots of this neutrality were multifaceted. Strong historical, cultural, and economic ties bound Argentina to continental Europe, particularly Germany, Italy, and Spain, nations from which a significant portion of its population originated.21 This contrasted with a traditional Argentine opposition to perceived US hegemonic ambitions in the Americas, often expressed in pan-American forums.19 Economic factors were also paramount; Argentina's economy was more complementary to Britain's than to the US's, with the UK heavily reliant on Argentine beef exports (up to 40% of its supply) during the war.19 This dependence led Britain to pressure Argentina to maintain neutrality to ensure the continued flow of vital supplies, resisting US calls for stronger sanctions against Buenos Aires.20 Internal dynamics, including divisions within the military and the influence of nationalist groups resentful of foreign economic dominance, further reinforced the neutral stance.18 This complex web of factors—economic dependencies, historical affinities, geopolitical positioning, and internal ideologies—meant that Argentina's neutrality was not passive isolation but an active policy choice, navigating competing international pressures and domestic interests. This environment, resistant to Allied alignment and influenced by European ties, created conditions conducive to post-war policies favorable towards Axis fugitives.

B. The Rise of Perón and the Political Climate

The political landscape that facilitated the post-war arrival of Nazis was significantly shaped by the ascent of Juan Domingo Perón. Perón became a dominant figure following the military coup of 1943 and was elected President in 1946.25 His political orientation included known sympathies towards European fascism; he had served as a military attaché in Benito Mussolini's Italy in the late 1930s and expressed admiration for the style and methods of fascist regimes, including their use of uniforms, rallies, and strong state apparatus.21

Perón's views resonated within influential segments of Argentine society. Pro-Axis sentiments were prevalent among wealthy businessmen, government officials, and particularly within military circles.19 Anti-Semitism was also a significant undercurrent in Argentine society during this period.21 Even before the war, Argentina had begun restricting Jewish immigration, culminating in the notorious secret "Directive 11" of 1938, signed by Foreign Minister José María Cantilo. This directive explicitly instructed Argentine consuls to deny visas to "undesirables or the expelled," a clear euphemism for Jews fleeing Nazi persecution.28 Figures like Perón's Minister of Immigration, Sebastian Peralta, were known anti-Semites who authored works warning against a perceived Jewish menace.22 While Perón himself later took pragmatic steps, such as appointing Jewish ministers and recognizing Israel, the underlying pro-fascist and anti-Semitic currents within his government and support base provided a welcoming atmosphere for fleeing Nazis and collaborators.22

C. US-Argentine Relations

Relations between Argentina and the United States were marked by considerable friction during and immediately following World War II.19 Washington viewed Argentina's neutrality with deep suspicion, interpreting it as alignment with the Axis.20Economic competition between the two nations, whose agricultural exports often competed in world markets, exacerbated political tensions.19 The US implemented economic sanctions, including withholding credit and halting shipments of vital goods like machinery and oil tankers, and refused to recognize the government of General Edelmiro Farrell, which came to power in 1944 and was seen by the US as consolidating pro-Axis influence.19

This tension culminated in the publication of the US State Department's "Argentine Blue Book" in February 1946. The document aimed to expose the pro-Axis policies pursued by Argentine governments during the war and warn of the potential for Argentina to become a base for resurgent Nazism.20 While the Blue Book generated significant anti-American sentiment in Argentina and may have inadvertently aided Perón's election campaign, it also appeared to foster some level of cooperation from the Argentine government regarding the control and liquidation of German assets.20This clash highlighted fundamentally different perceptions: the US saw pro-Nazi collaboration, while many Argentines likely viewed US actions as unwarranted interventionism, reinforcing their commitment to an independent path.19 Despite these deep-seated tensions, the post-war landscape began to shift with the onset of the Cold War. The United States' desire for hemispheric unity against the perceived communist threat led to an improvement in relations with Argentina by late 1946, prioritizing geopolitical alignment over past grievances concerning wartime neutrality and Axis sympathies.20 This strategic realignment, however, did not erase the underlying issues or the reality of Argentina's role as a developing haven for Nazi fugitives.

III. Operation Ratlines: Argentina's Facilitation of Nazi Escape

A. Perón's Active Role

The files unequivocally establish a state-organized infrastructure for the arrival of Nazi figures. For instance, Adolf Eichmann's Argentine identity documents under the alias “Ricardo Klement” appear in multiple state records. These include fingerprint forms, immigration approvals, and residency certificates showing full knowledge of his presence by Argentine authorities as early as the 1950s.

Josef Mengele’s detailed case file reveals his initial entry under the alias “Helmut Gregor,” including registration with national police, residence information in the suburbs of Buenos Aires, and his 1956 application for a national identity document under his real name, which was granted without issue.

Walter Kutschmann, alias Pedro Ricardo Olmo, was also heavily documented. Surveillance photographs, bank account records, and employment details appear in his multi-volume file, which traces his movements across various provinces and includes evidence of delayed or obstructed extradition attempts.

Contrary to any notion of passive acceptance or mere negligence, the government of Juan Domingo Perón played an active, deliberate, and secret role in facilitating the escape and settlement of Nazi war criminals and collaborators in Argentina during the late 1940s.1 Evidence indicates that Perón personally instructed Argentine diplomats and intelligence officers to establish and manage clandestine escape routes, commonly referred to as "ratlines".1 Argentine agents, including figures like Carlos Fuldner, a former SS agent of Argentine-German background, were dispatched to key locations in Europe—primarily Spain, Italy, Switzerland, and Scandinavia—with explicit orders to assist fleeing Nazis.23

This assistance involved organizing passage, providing necessary (often falsified) travel documents, and, in many cases, covering expenses associated with the journey to South America.21 This state-sponsored operation demonstrates a clear policy choice by the Perón administration, highlighting Argentina's direct agency in enabling the escape of individuals wanted for horrific crimes.

B. Motivations Behind the Policy

The Perón government's decision to actively aid Nazi fugitives stemmed from a complex interplay of motivations, rather than a single overriding factor:

Ideological Sympathy: Perón harbored an affinity for European fascism, influenced by his time in Mussolini's Italy.21 He reportedly viewed the escaping Nazis and collaborators not as war criminals but as "brothers-in-arms" being unjustly persecuted by the victors.23 His reported anger over the Nuremberg Trials further reflects this perspective.23

Strategic/Technical Gain: A key motivation was the desire to recruit individuals possessing valuable military, scientific, and technical expertise.1 Perón believed these specialists could contribute to Argentina's industrialization and military development, mirroring efforts by both the United States and the Soviet Union to secure German scientific talent during the emerging Cold War.1 The subsequent investigation by the Commission for the Clarification of Nazi Activities in Argentina (CEANA) specifically examined the employment of Nazi and other foreign technicians by the Argentine Army, lending credence to this motive.31

Anti-Communism: Perón perceived an inevitable global conflict between capitalism and communism and believed that experienced, battle-hardened, and vehemently anti-communist Nazi veterans could prove useful assets for Argentina in such a scenario.21 This aligned with his broader geopolitical vision of positioning Argentina as a "Third Way" between the two superpowers.21

Financial Incentive: There was a potential economic dimension to the policy. Escaping Nazis sometimes brought significant wealth with them, including assets plundered during the war.21 The operation was also reportedly bankrolled, at least in part, by sympathetic and wealthy members of the German-Argentine community, channeled through Perón's government.21 The case of Croatian Ustasha leader Ante Pavelić arriving with chests of gold and valuables stolen from victims illustrates this potential financial element.21 Ongoing investigations into the role of banks like Credit Suisse in potentially holding Nazi-linked accounts in Argentina further point to financial facilitation networks.2

Pragmatism vs. Ideology: The policy existed alongside seemingly contradictory actions by Perón, such as appointing Jewish individuals to ministerial positions and being among the first nations to recognize the state of Israel.22 This suggests a complex political calculus, balancing ideological leanings with pragmatic considerations of national interest, economic contributions from the established Jewish community, and domestic political maneuvering.22 The presence of virulent anti-Semites like Immigration Minister Peralta within the administration highlights the regime's internal contradictions.22 This intricate mix of ideology, realpolitik, perceived strategic advantage, and potential financial gain shaped a policy that actively welcomed perpetrators of war crimes.

IV. Mechanisms of Sanctuary: Networks and Methods

A. International Networks

The escape of thousands of Nazis and collaborators from post-war Europe was facilitated by sophisticated international networks operating across multiple countries. These "ratlines" primarily channeled fugitives towards havens in the Americas, with Argentina emerging as the most significant destination, receiving estimates of up to 5,000 individuals.1 Other South American nations like Brazil, Chile, and Paraguay also received smaller numbers.1

Key European transit points were crucial nodes in these networks. Ports and cities in Spain and Italy (particularly Genoa) served as major embarkation points.1 Switzerland, Scandinavia, and Belgium also functioned as conduits in the escape routes established or utilized by Argentine agents.23 The role of Spain as a transit hub was considered significant enough to warrant specific investigation by the later CEANA commission.31

Controversially, elements within the Catholic Church were implicated in facilitating these escapes.1 Figures such as the Austrian Bishop Alois Hudal in Rome and the Croatian priest Krunoslav Draganović were known to have aided fleeing Nazis and fascists.1 While some church officials may have unwittingly assisted criminals amidst genuine efforts to help refugees displaced by the war and the rise of communism, others like Hudal, an admirer of Hitler, acted with full knowledge, providing crucial assistance like false identity documents.1 High-ranking church officials, including Argentine Cardinal Antonio Caggiano and French Cardinal Eugène Tisserant, reportedly interceded to help specific collaborators emigrate to Argentina.1 Vatican diplomatic channels had also explored Argentina's willingness to accept European Catholic immigrants as early as 1942.30 Adding another layer of complexity, U.S. intelligence agencies reportedly utilized some of these existing ratline structures after 1947 to relocate certain Nazi strategists and scientists deemed useful for Cold War purposes.30 The success of these escape routes thus depended on a confluence of state sponsorship (Argentina), transnational clerical and diplomatic connections, institutional loopholes, and sympathetic communities.

B. Methods of Escape and Settlement

The practical execution of the ratlines relied on specific methods, primarily involving fraudulent documentation and financial support:

Documentation: The acquisition of false or manipulated identity and travel documents was paramount. A common method involved obtaining passports from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).1 These were often secured using false identity papers provided by facilitators like Bishop Hudal.1 Adolf Eichmann famously entered Argentina using such a passport under the alias Ricardo Klement, and estimates suggest hundreds of other SS members may have used similar means.1 These ICRC passports were then frequently stamped with Argentine visas, often simple tourist visas, enabling legal entry into the country.1 In some cases, Vatican-issued identity documents were used as a preliminary step to obtain the ICRC passports.1 This exploitation of humanitarian documentation stands in stark contrast to legitimate rescue efforts during the same period, such as the issuance of thousands of life-saving Salvadoran passports to Jews by diplomats George Mantello and José Castellanos.27

Financial Support: The logistical and travel expenses associated with the ratlines were often covered by funds from various sources. Wealthy individuals within the established German-Argentine community reportedly contributed significantly, often channeling funds through Perón's government.21 There is also evidence suggesting that some escaping Nazis brought substantial personal wealth, potentially including assets looted from Holocaust victims.21 The extensive investigations launched in the 21st century into the historical dealings of banks like Credit Suisse with Nazi-linked accounts in Argentina point towards institutional financial facilitation of these escape networks.2

Integration: Upon arrival in Argentina, fugitives often benefited from the presence of large, pre-existing German-speaking communities, which provided a degree of cover and facilitated integration.25 The Perón government sometimes provided direct assistance, including money and employment opportunities, to help the newcomers establish themselves.23 This combination of falsified identities, financial backing, and community support allowed many Nazis to disappear into Argentine society.

The co-option of humanitarian mechanisms like the ICRC passport system represents a disturbing historical irony. Systems designed to aid the displaced and vulnerable were systematically exploited by networks dedicated to helping perpetrators evade justice, highlighting the ethical complexities and institutional vulnerabilities of the immediate post-war era.

V. Argentina as a Haven: The Lives and Fates of Fugitive Nazis

A. Prominent Fugitives

Documents confirm that fugitives were not simply hiding—they were integrating. Mengele is recorded as having run a business importing medical supplies. Eichmann worked at a Mercedes-Benz plant, and Kutschmann was employed in the textile sector. These employment records, immigration affidavits, and tax filings suggest systemic normalization of their presence. Argentina became a sanctuary for numerous high-profile Nazi war criminals. Recent declassifications in 2025 have shed further light on their activities within the country.2

Josef Mengele ("Angel of Death"): The infamous Auschwitz physician arrived in Buenos Aires in June 1949.17 He initially used the alias Helmut Gregor 17 or Gregor Helmut 2, claiming to be a mechanic or technician from Italy.2 Strikingly, intelligence records indicate he initially lived openly under his real name before adopting the alias.2 He resided at known addresses in the Buenos Aires suburbs of Florida and Monserrat.2 Mengele integrated into the German community, engaging in business activities.27 In 1956, he applied for and received new Argentine identity documents under his actual name, Jose Mengele.6 He even traveled to Uruguay in 1958 to marry his deceased brother's widow, Marta Maria Will, under his own name, and formally adopted his nephew.2 Despite a West German extradition request, Argentine authorities declined to act, citing technicalities or the need for review due to the alleged "political" nature of his crimes.2 Intelligence files confirm no measures were taken against him by Argentine authorities at the time.2 Facing increased scrutiny, potential extradition, and a changing political climate (particularly before Eichmann's capture), Mengele fled Argentina around 1959.3 He found refuge first in Paraguay and later in Brazil, where he drowned in 1979 under an assumed identity, his fate only confirmed by forensic analysis in 1985.1

Adolf Eichmann (Holocaust Architect): Eichmann arrived in Argentina in 1950 using the alias Ricardo Klement.3 His passage was facilitated by a falsified Red Cross passport obtained with the help of a Franciscan monk in Genoa.1 He settled with his family in the Buenos Aires suburbs of Lanús 2 and San Fernando 17, working at a Mercedes-Benz factory.1 Declassified files suggest he lived undisturbed with the knowledge of Argentine authorities.2 During his time in Argentina, Eichmann reportedly boasted openly about his central role in the Holocaust in tape-recorded conversations with Nazi sympathizer Willem Sassen.34 His life in hiding ended dramatically in May 1960 when he was abducted from a street near his home by agents of Israel's Mossad.2 Recently declassified documents suggest the possibility of assistance from elements within Argentina's security forces during the operation 17, although the capture surprised the CIA.36 Eichmann's abduction triggered a severe diplomatic crisis between Argentina and Israel, involving the recall of ambassadors and an appeal by Argentina to the UN Security Council over the violation of its sovereignty.19 Israel eventually issued a formal apology.35 Eichmann was covertly transported to Israel, where he stood trial, was convicted of crimes against humanity, and executed by hanging in 1962.2

Erich Priebke (SS Officer, Ardeatine Massacre): A former SS Hauptsturmführer responsible for the 1944 Ardeatine Caves massacre in Rome, Priebke arrived in Argentina in 1948.2 He lived openly for decades in the Patagonian city of Bariloche, a popular destination for German immigrants.2 His past was exposed by media reports in the early 1990s, leading to his extradition to Italy in 1994 or 1995 to face trial.2 The recently declassified Argentine files include the 1995 presidential decree signed by Carlos Menem authorizing his extradition.2

Other Figures: The archives and reports also mention other significant Nazi figures linked to Argentina. Martin Bormann, Hitler's powerful private secretary, allegedly arrived in 1948 17, and a 1960 file reportedly contains his fingerprints 6(though historical consensus holds Bormann died in Berlin in 1945). Walter Rauff, creator of mobile gas vans, found refuge in Chile after likely passing through other countries, dying there in 1984.1 Eduard Roschmann, the "Butcher of Riga," fled Argentina and died in Paraguay in 1977.1 Gustav Wagner, the "Beast" of Sobibor, died in Brazil in 1980 after extradition attempts failed.1 Gestapo officer Walter Kutschmann and concentration camp commandant Edward Roschmann (likely the same as Eduard) are also named in connection with the files.37 Croatian leader Ante Pavelić also found refuge for a time.21 Additionally, figures like Franz Alfred Six and Otto Von Bolschwing, associates of Eichmann, later became assets for the CIA.36

B. Life in Argentina

The granting of legitimate national documents to these fugitives—despite known identities—points to deliberate bureaucratic endorsement rather than oversight. The presence of military and intelligence correspondence in several folders confirms a network of state officials who either protected or ignored their presence. For many Nazi fugitives, life in Argentina offered a chance to escape prosecution and rebuild their lives, often under the protective cover of the country's large German diaspora.25While some, like Mengele initially 2, lived openly, most adopted aliases and attempted to maintain a low profile, fearing discovery and potential repercussions.21 The Perón government provided initial support, including money and jobs, to facilitate their settlement.23 However, the overthrow of Perón in 1955 created a period of anxiety among the hidden Nazis, who feared that the new, anti-Peronist administration might be less inclined to protect them and could potentially extradite them to Europe.21Despite this uncertainty, many continued to live undisturbed for years, even decades.

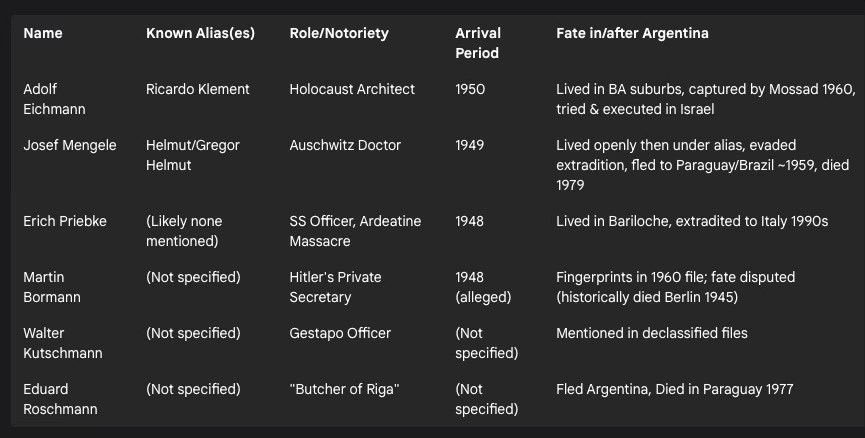

C. Table: Key Nazi Fugitives Associated with Argentina (Based on Provided Sources)

The following table summarizes information on some of the most prominent Nazi fugitives linked to Argentina, based on the available documentation:

This table provides a concise overview, facilitating comparison of the experiences of these individuals within the Argentine context. Their varied fates—successful evasion, capture and trial, or late extradition—illustrate that Argentina's role as a haven was not monolithic or static. It evolved over time, influenced by individual circumstances, international actions, and domestic political shifts. Mengele's ability to live openly for a period and ultimately evade Argentine justice highlights institutional failures or a lack of political will, while Eichmann's dramatic capture, despite violating Argentine sovereignty, forced an international confrontation. Priebke's much later extradition, occurring after the restoration of democracy, signals a significant shift in state policy towards accountability. The Eichmann affair, in particular, created a major diplomatic rupture but also served as a powerful catalyst, bringing global attention to Argentina's role and likely contributing to increased long-term pressure for transparency and justice.

VI. Confronting the Past: Archives, Investigations, and Transparency

A. The Archivo General de la Nación (AGN) Nazi Files

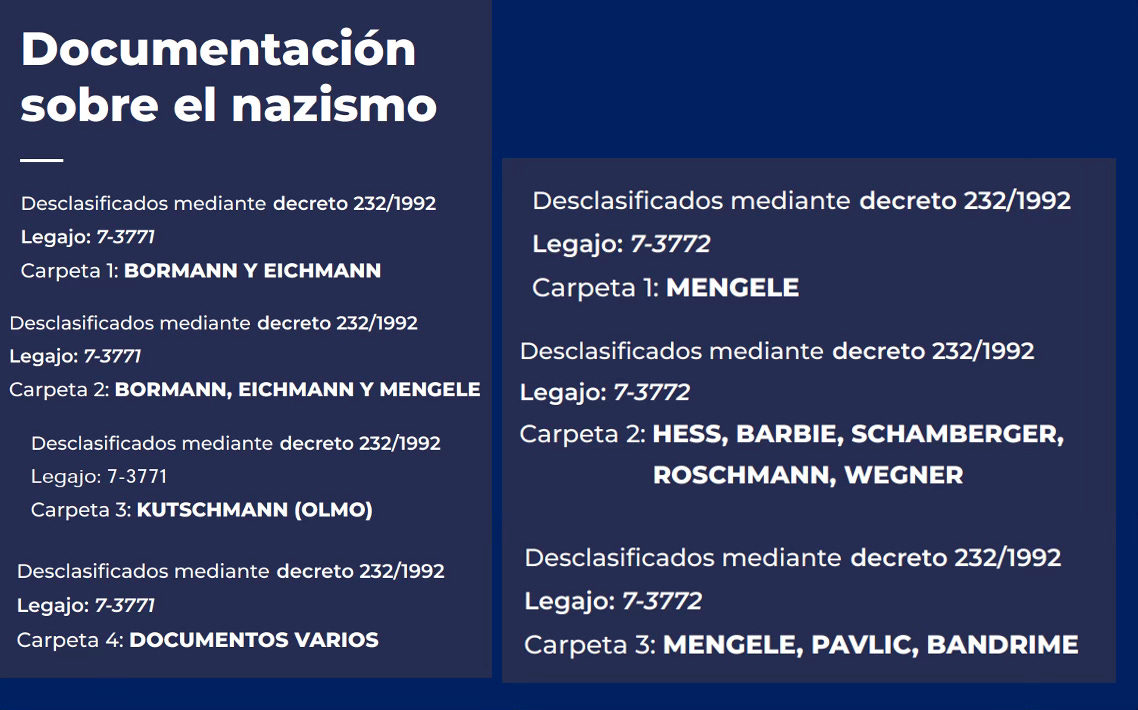

Central to understanding Argentina's post-war relationship with Nazism is the collection of documents held by the Archivo General de la Nación (AGN). This collection specifically focuses on the arrival and subsequent activities of Nazi leaders, war criminals, and collaborators who sought refuge in Argentina after World War II.9

The core of this documentation originates from investigations conducted over several decades, primarily between the 1950s and 1980s, by various Argentine state agencies.6 These include the Directorate of Foreign Affairs of the Federal Police, the State Intelligence Secretariat (SIDE, Argentina's main intelligence agency), and the National Gendarmerie.9

The size and structure of the collection have been described somewhat inconsistently. An AGN webpage mentions over 1850 documents organized into 7 files.9 Reports surrounding the 2025 declassification frequently refer to the release of 1,850 files 2 or 1,850 documents.4 Regardless of the precise terminology, it represents a substantial body of material.

Based on reports concerning the 2025 online release, the files contain a variety of valuable records:

Financial Records: Details of banking operations and financial transactions potentially linked to Nazi fugitives and their settlement.2

Intelligence and Police Files: Secret intelligence bulletins, reports from SIDE and the Federal Police, police records (such as Mengele's identity document applications), and fingerprint records (like those attributed to Martin Bormann).2

Government and Military Records: Confidential Defence Ministry reports and official decrees, including extradition orders (like Priebke's 1995 decree) and potentially information related to arms deals, budgetary matters, and the organization of intelligence services.2

Press Reports: Contemporary press clippings related to the activities and tracking of Nazi figures.6

B. Declassification Efforts

Argentina's path towards making these sensitive archives accessible has been gradual and occurred in distinct phases:

1992 Declassification: The initial significant step towards transparency came under President Carlos Menem with Presidential Decree 232/1992.7 This decree formally lifted the "reasons of State" secrecy classification that had previously shielded documentation related to Nazi criminals.9 It mandated that relevant state organizations transfer all such reserved documents to the AGN.9 Around the same time, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs reportedly declassified a large volume of documents (cited as 139,544).4 However, a major limitation of this 1992 initiative was accessibility; the declassified AGN materials could only be consulted physically within a designated room at the archive headquarters in Buenos Aires.4

2025 Declassification/Online Release: A major advancement occurred in 2025 under President Javier Milei, who ordered the full declassification and online publication of the AGN's Nazi-related holdings.2 This move was explicitly prompted by requests from the Simon Wiesenthal Center and U.S. Senator Steve Daines 2 or Chuck Grassley 4 (reports vary on the specific senator involved), linked to an ongoing U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee investigation into Nazi assets potentially held by Credit Suisse and its predecessor banks.2 This initiative made the approximately 1,850 documents (or files) digitally accessible to researchers and the public worldwide via the AGN's online platform.2 The release also included nearly 1,300 previously secret or confidential presidential decrees spanning from 1957 to 2005, covering a range of sensitive topics beyond Nazism.5

This progression from concealment to limited physical access, and finally to broad digital transparency, illustrates a significant evolution in Argentina's official approach to its historical archives. It suggests that while initial steps were taken in the early 1990s, the impetus for full online accessibility in 2025 was strongly influenced by contemporary international investigations and external pressure from NGOs and foreign governmental bodies.

C. The CEANA Commission (Commission for the Clarification of Nazi Activities in Argentina)

Another key element in Argentina's official reckoning with this past was the establishment of the "Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de las Actividades del Nazismo en la Argentina" (CEANA) in 1997, also during the Menem presidency.31 Its mandate was later extended.40

Initially tasked with estimating the number of Nazi war criminals who settled in Argentina and investigating the potential entry of Nazi-looted assets, CEANA's scope expanded significantly.31 Its final report, a substantial volume of over 674 pages presented in late 1999, covered a wide array of topics across twenty chapters.31These included analyses of the connections between European fascism and Argentine political culture, the impact of Nazi presence on the integration of Jews into the diplomatic corps, the employment of Nazi technicians by the Argentine military, and the role of Spain as a transit country.31 One of CEANA's key findings was an estimate that approximately 180 Nazi war criminals had migrated to Argentina, primarily between 1946 and the mid-1950s.7

Despite its official mandate and extensive output, CEANA was not without controversy. Some researchers, notably Uki Goñi (author of "The Real Odessa"), criticized the commission, alleging it faced difficulties accessing crucial documents within Argentine archives and ultimately obscured rather than clarified certain aspects of the history, leading Goñi himself to resign from the commission.40 Conversely, figures associated with CEANA, like historian Ignacio Klich, defended its work, emphasizing the need to understand the historical context.29 CEANA's recommendations also played a role in the controversial placement of a commemorative plaque in the Foreign Ministry honoring diplomats, some of whom were later accused of inaction or obstruction regarding the rescue of Jews, further fueling debate about the commission's interpretations and legacy.28 The existence and contested reception of CEANA underscore the inherent challenges and political sensitivities involved when states attempt to officially investigate complex and compromising aspects of their own history. Such commissions can yield valuable research but often become arenas for conflicting interpretations and political debate.

VII. Shifting Tides: International Pressure and Evolving Policies

A. From Sanctuary to Scrutiny

Argentina's posture towards Nazi fugitives underwent a significant transformation over the decades following World War II. The initial period under Juan Perón (1946-1955) was characterized by active, state-sponsored facilitation of escape and the provision of sanctuary.1 Following Perón's overthrow in 1955, the situation became less certain for the hidden Nazis.21 While the overt state support diminished, many fugitives continued to live in relative safety for years, exemplified by Adolf Eichmann's undisturbed residence until 1960 and Josef Mengele's until roughly 1959, while Erich Priebke remained undetected for decades.2

A critical turning point was the capture of Adolf Eichmann by Israeli Mossad agents in Buenos Aires in 1960.19 This audacious operation, though condemned by Argentina as a violation of sovereignty 35, dramatically thrust Argentina's role as a Nazi haven into the international spotlight. It exposed the vulnerability of even high-profile fugitives and undoubtedly increased pressure on subsequent Argentine governments to address the issue, marking a shift from quiet sanctuary towards heightened scrutiny.

B. International Pressure and Actions

External actors played a crucial role in driving this shift:

Israel (Mossad): The Israeli intelligence agency took direct action with the Eichmann abduction, demonstrating a willingness to operate extraterritorially to bring Holocaust perpetrators to justice.2

Nazi Hunters / NGOs: Organizations dedicated to tracking Nazi war criminals and advocating for historical truth maintained persistent pressure. The Simon Wiesenthal Center, named after the famed Nazi hunter, has been particularly active, involved in tracking fugitives, demanding access to archives, pushing for declassification (including the 1992 and 2025 initiatives), and participating in recent investigations concerning Nazi-linked finances at institutions like Credit Suisse.2 The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation also actively called for transparency regarding Argentina's past, particularly concerning restrictive immigration policies towards Jews and the honoring of controversial diplomats.28

Foreign Governments/Bodies: Various states and international bodies exerted influence at different times. The United States applied significant pressure during and immediately after the war regarding neutrality and Axis assets.18 The UN Security Council became involved following the Eichmann capture due to Argentina's complaint.35 West Germany submitted extradition requests for figures like Mengele, although these were initially rebuffed by Argentina.3 More recently, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee's investigation into Credit Suisse, led by Senator Grassley or Daines, directly prompted the 2025 declassification and online release of AGN files.2

C. Evolution of Argentine Policy

In response to both internal political changes and external pressures, Argentine policy gradually evolved:

Initial Resistance: In the decades immediately following the war, and even after Perón, there was often resistance or deliberate delay in cooperating with extradition requests, as seen in the handling of Mengele's case.3

Shift Post-Democracy: A significant change occurred following the restoration of democracy in Argentina in 1983.17 Subsequent democratic governments demonstrated a greater willingness to cooperate with international justice efforts. This shift is clearly illustrated by the extradition of Erich Priebke to Italy in the mid-1990s after his past was publicly exposed.2

Official Reckoning: The creation of the CEANA commission in 1997 and the declassification initiatives of 1992 and 2025 represent official, state-sanctioned steps—albeit sometimes contested or externally prompted—towards investigating and acknowledging this difficult period of national history.5

This long-term evolution demonstrates that Argentina's approach was heavily influenced by the interplay between domestic political transitions—particularly the shift from authoritarian regimes (including military dictatorships) to democracy—and sustained pressure from international actors. Democratic openings provided crucial opportunities for external pressure from NGOs, foreign governments, and international bodies to translate into concrete policy changes towards greater accountability and transparency. Furthermore, the issue of Nazi fugitives in Argentina did not exist in a vacuum; it became intertwined with broader geopolitical dynamics, including Cold War alignments that initially saw the US prioritize anti-communism over confronting Argentina's Nazi ties 20, later debates over national sovereignty versus international justice sparked by the Eichmann affair 35, and contemporary international financial investigations.2 Understanding this wider context is essential for comprehending the timing and nature of Argentina's policy shifts.

VIII. Conclusion: Legacy and Lingering Questions

A. Synthesis of Findings

The available evidence clearly indicates that Argentina, particularly under the administration of Juan Domingo Perón, played a definitive and active role in the post-World War II era as a sanctuary for Nazi war criminals and collaborators. This was not a passive acceptance but a state-facilitated operation driven by a complex mixture of ideological affinity with fascism, perceived strategic benefits in acquiring technical and military expertise, anti-communist geopolitical calculations, and potential financial incentives. Sophisticated "ratlines," supported by Argentine agents abroad and exploiting international networks and institutional vulnerabilities (such as the ICRC passport system), enabled the arrival of thousands of fugitives, including notorious figures like Eichmann and Mengele. While many attempted to live quiet lives integrated within Argentina's German communities, their presence constituted a significant moral and political failure, shielded for years by varying degrees of official complicity or inaction.

B. The Long Road to Transparency

Argentina's confrontation with this troubling past has been a protracted and often politically charged process spanning decades. It moved slowly from periods of active complicity and subsequent concealment towards investigation, exemplified by the CEANA commission, and gradual declassification of state archives. The initial declassification in 1992 under President Menem represented a crucial step, but access remained limited. The comprehensive online release of the Archivo General de la Nación's Nazi-related files in 2025, prompted significantly by external pressure related to international financial investigations, marks a watershed moment in transparency, making primary source material widely accessible for the first time.2This evolution highlights how historical reckoning is often incremental and influenced by contemporary political dynamics and international stimuli.

C. Historical Significance and Impact

The legacy of Argentina's role as a Nazi haven has had a lasting impact on its international image and its relationship with the global Jewish community and nations like Israel. While some argue that the fugitive Nazis themselves had limited long-term influence on Argentine society, many having lived quietly 21, the act of providing them sanctuary raised profound ethical questions and represented a failure to uphold international justice in the immediate post-Holocaust era. The capture of Eichmann and the later extradition of Priebke underscored the tension between national sovereignty and the demands of accountability for crimes against humanity. The willingness of recent Argentine governments to declassify archives signals a commitment to confronting this history, contributing to a more complete understanding of the post-war period and the global networks that facilitated the escape of perpetrators.

D. Unanswered Questions/Future Research

Despite recent advances in transparency, questions remain. The full extent and mechanics of the financial networks supporting the ratlines and the fugitives' lives in Argentina, particularly the role of international banks like Credit Suisse, are still under active investigation.2 The complete analysis and interpretation of the newly digitized AGN documents will require time and scholarly effort to fully reveal their implications regarding specific individuals, state operations, arms deals, intelligence activities, and Cold War dynamics mentioned in preliminary reports.2 The ongoing process of research and analysis, fueled by greater archival openness, promises to further illuminate this complex and significant chapter of 20th-century history.

Works cited

How South America Became a Nazi Haven | HISTORY - History.com, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.history.com/articles/how-south-america-became-a-nazi-haven

Argentina opens up secret Nazi fugitive files to public | Buenos Aires ..., accessed May 3, 2025, https://batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/argentina-opens-up-secret-nazi-fugitive-files-to-public.phtml

The 7 Most Notorious Nazis Who Escaped to South America - History.com, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.history.com/articles/the-7-most-notorious-nazis-who-escaped-to-south-america

Argentina declassifies over 1,800 files on Nazi 'ratline' escape ..., accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.timesofisrael.com/argentina-declassifies-over-1800-files-on-nazi-ratline-escape-routes-after-wwii/

Argentina releases huge trove of declassified Nazi and dictatorship ..., accessed May 3, 2025, https://buenosairesherald.com/politics/argentina-releases-huge-trove-of-declassified-nazi-and-dictatorship-documents

Argentina Releases Declassified Post-WWII Nazi-Related Files ..., accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.newsweek.com/argentina-releases-trove-declassified-nazi-documents-2065654

Argentina announces declassification of documents on Nazis who fled to the country, accessed May 3, 2025, https://buenosairesherald.com/world/international-relations/argentina-announces-declassification-of-documents-on-nazis-who-fled-to-the-country

Report of the Independent Ombudsperson and Independent Advisor to Credit Suisse - Senator Chuck Grassley, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.grassley.senate.gov/download/revised-report-of-the-independent-ombudsperson-and-independent-advisor-to-cs

Documentación sobre el nazismo | Argentina.gob.ar, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/interior/archivo-general-de-la-nacion/documentacion-sobre-el-nazismo

www.argentina.gob.ar, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/agn-7-3772-3.pdf

accessed January 1, 1970, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/agn-7-3772-2_0.pdf

www.argentina.gob.ar, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/agn-7-3772-1.pdf

www.argentina.gob.ar, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/agn-7-3771-4.pdf

www.argentina.gob.ar, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/agn-7-3771-3.pdf

www.argentina.gob.ar, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/agn-7-3771-2.pdf

www.argentina.gob.ar, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/agn-7-3771-1.pdf

The trail of Nazis Mengele and Eichmann in Argentina | International ..., accessed May 3, 2025, https://english.elpais.com/international/2025-04-30/the-trail-of-nazis-mengele-and-eichmann-in-argentina.html

Argentina during World War II - Wikipedia, accessed May 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argentina_during_World_War_II

ARGENTINA, WORLD WAR II, AND THE ENTRY OF NAZI ... - Brill, accessed May 3, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789047441489/Bej.9789004179134.i-286_005.pdf

1997-2001.state.gov, accessed May 3, 2025, https://1997-2001.state.gov/regions/eur/rpt_9806_ng_summary.pdf

Why Argentina Accepted Nazi War Criminals After World War II - ThoughtCo, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.thoughtco.com/why-did-argentina-accept-nazi-criminals-2136579

Why did Argentina offer asylum to former Nazis? : r/history - Reddit, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/history/comments/9n1om2/why_did_argentina_offer_asylum_to_former_nazis/

Juan Domingo Peron and Argentina's Nazis - ThoughtCo, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.thoughtco.com/juan-domingo-peron-and-argentinas-nazis-2136208

The day Argentina declared war on the Axis | Buenos Aires Times, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/the-day-argentina-declared-war-on-the-axis.phtml

Why did so many Germans choose to move to Argentina after World War II? - Reddit, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/18gs1f/why_did_so_many_germans_choose_to_move_to/

en.wikipedia.org, accessed May 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argentina_during_World_War_II#:~:text=In%20the%20late%201940s%2C%20under,as%20part%20of%20the%20ratlines.

The Perfect Hideout: Jewish and Nazi havens in Latin America, accessed May 3, 2025, https://wienerholocaustlibrary.org/exhibition/the-perfect-hideout-jewish-and-nazi-havens-in-latin-america/

Continuing Efforts to Conceal Anti-Semitic Past, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.raoulwallenberg.net/education/diplomacy/argentina-75/continuing-efforts-conceal/

Argentines angry over WWII actions - Jewish Telegraphic Agency, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.jta.org/2005/05/12/lifestyle/argentines-angry-over-wwii-actions

Ratlines (World War II) - Wikipedia, accessed May 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ratlines_(World_War_II)

www.cia.gov, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/NAZIS%20ESCAPE%20ROUTES%20SO.%20AMERICA%20%20%28DI%20SEARCH%29_0010.pdf

Secret documents on Nazis who fled to Argentina after WWII being declassified, accessed May 3, 2025, https://news.yahoo.com/secret-documents-nazis-fled-argentina-180017993.html

Argentina To Declassify Archives On Nazis Who Took Refuge After World War II - i24NEWS, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.i24news.tv/en/news/international/latin-america/artc-argentina-to-declassify-archives-on-nazis-who-took-refuge-after-world-war-ii

The Long Road to Eichmann's Arrest: A Nazi War Criminal's Life in Argentina - Spiegel, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/the-long-road-to-eichmann-s-arrest-a-nazi-war-criminal-s-life-in-argentina-a-754486.html

Special publication: Behind the scenes at the Eichmann Trial |, accessed May 3, 2025, https://catalog.archives.gov.il/site/en/chapter/behind-scenes-eichmann-trial/

The CIA Names File on Adolf Eichmann - The National Security Archive, accessed May 3, 2025, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB150/index.htm

Argentina declassifies archives on Nazi war criminals who fled after World War II | Caliber.Az, accessed May 3, 2025, https://caliber.az/en/post/argentina-declassifies-archives-on-nazi-war-criminals-who-fled-after-world-war-ii

Argentina declassifies series of documents about Nazis in country - The Jerusalem Post, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.jpost.com/diaspora/antisemitism/article-852238

Argentina declassifying docs on Nazi fugitives, reignites Hitler conspiracy, accessed May 3, 2025, https://san.com/cc/argentina-declassifying-docs-on-nazi-fugitives-reignites-hitler-conspiracy/

Enlightenment on Argentina and the Third Reich - The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.raoulwallenberg.net/articles/argenazis/enlightenment-argentina-third/

Argentina and the Nazis: a necessary debate, accessed May 3, 2025, https://www.raoulwallenberg.net/news/argentina-nazis-necessary/