- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- This report addresses the constitutional and legal mechanisms available to counter a scenario in which the executive branch is perceived to be operating beyond the constraints of law...

This report addresses the constitutional and legal mechanisms available to counter a scenario in which the executive branch is perceived to be operating beyond the constraints of law...

...using state agencies for coercion, and systematically ignoring the constitutional order. The actions of a leader fostering a "cult of personality" might constitute profound abuses of power.

Mechanisms of Accountability and Constraint on Executive Power in a Constitutional Crisis

by Gemini 2.5 Pro, Deep Research. Warning! LLMs may hallucinate!

Introduction: The Constitutional Framework for Addressing Executive Overreach

This report addresses the constitutional and legal mechanisms available to counter a scenario in which the executive branch is perceived to be operating beyond the constraints of law, using state agencies for coercion, and systematically ignoring the constitutional order. The framers of the U.S. Constitution anticipated the potential for such executive overreach and designed a system of separated powers and checks and balances as the primary defense against tyranny.1 The inquiry describes a phenomenon that political scientists term "executive aggrandizement" or "democratic backsliding," where elected leaders incrementally dismantle democratic checks and balances.4 The use of the term "cult" suggests a "cult of personality," a political dynamic where a leader is presented as infallible and commands loyalty that supersedes allegiance to the law or the Constitution.5 This dynamic, analyzed through the lens of political science theories of authoritarianism—which emphasize concentrated power, repression, and the exclusion of challengers—provides the framework for this analysis.6

The following sections provide an exhaustive examination of the constitutional and legal tools available to counter such a threat. The analysis will proceed from the most direct and constitutionally prescribed remedies to the broader powers of constraint held by the other branches, the legal limits on coercive force, and the crucial role of non-governmental actors. Each mechanism will be evaluated not only on its theoretical function but also on its practical efficacy and limitations in a high-stakes, time-sensitive crisis.

Part I: Formal Mechanisms for Removal from Office

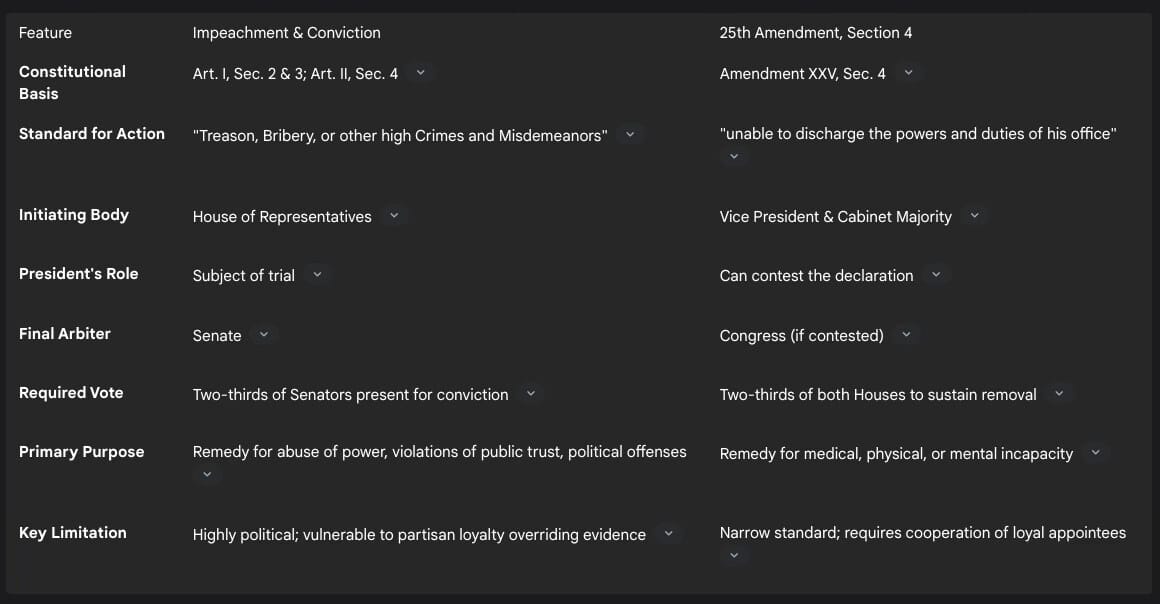

The U.S. Constitution provides two explicit pathways for removing a President from office. These mechanisms, impeachment and the 25th Amendment, are distinct in their purpose, procedure, and the standards required for their application. An assessment of their viability in a scenario characterized by intense political loyalty to the executive reveals both their intended power and their practical limitations.

Section 1.1: Impeachment and Conviction: The Ultimate Political Check

The Constitution's primary remedy for a chief executive who abuses power is the impeachment process. It is a fundamental component of the system of checks and balances, designed as a political, rather than criminal, proceeding to remove officials who violate the public trust.1

Constitutional Foundation and Process

The power of impeachment is divided between the two houses of Congress. Article I grants the "sole Power of Impeachment" to the House of Representatives and the "sole Power to try all Impeachments" to the Senate.1 The procedure unfolds in several distinct stages:

Inquiry and Investigation: An impeachment proceeding formally begins with a resolution in the House of Representatives, which is typically referred to a committee, most often the Committee on the Judiciary, to conduct an inquiry.11 This phase involves gathering evidence, hearing testimony, and determining whether sufficient grounds for impeachment exist.

Articles of Impeachment: If the committee finds sufficient evidence of wrongdoing, it drafts articles of impeachment, which are the specific charges against the official. The full House of Representatives then debates and votes on these articles. A simple majority vote is required to impeach the official.11

Senate Trial: Upon impeachment by the House, the process moves to the Senate, which sits as a "High Court of Impeachment".1 A team of representatives, known as "managers," acts as the prosecution. In the case of a presidential impeachment, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court presides over the trial.1

Conviction and Removal: A conviction requires a two-thirds supermajority vote of the senators present.1 The penalties are strictly remedial: removal from office and, in a separate vote, potential disqualification from holding any future federal office. An impeached and convicted official may still be subject to criminal prosecution in the courts after removal.9

The Standard: "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors"

The constitutional standard for impeachment is outlined in Article II, Section 4.2 While "treason" and "bribery" are specific, well-defined crimes, the phrase "other high Crimes and Misdemeanors" is intentionally broad and is not limited to indictable criminal offenses.2 Historical practice and constitutional scholarship confirm that this standard encompasses a wide range of misconduct. It includes grave abuses of power, violations of the public trust, and actions that fundamentally undermine the constitutional order. As Justice Joseph Story noted, the term reaches "political offences, growing out of personal misconduct, or gross neglect, or usurpation, or habitual disregard of the public interests".2 This breadth is critical, as the actions of a leader fostering a "cult of personality" might constitute profound abuses of power without necessarily violating a specific criminal statute.

Historical Precedent and Political Reality

The impeachment power has been used sparingly, particularly against presidents. The House has initiated impeachment proceedings more than 60 times since 1789, but only 21 federal officials have been impeached.12 Of those, only eight—all federal judges—were convicted by the Senate and removed from office.12 No U.S. president has ever been removed from office through impeachment and conviction. The impeachment trials of Presidents Andrew Johnson, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump underscore that the process is fundamentally political, where partisan allegiance often outweighs the evidence presented.12

In a hyper-partisan environment, particularly one in which a president commands intense loyalty from their political party, achieving a two-thirds Senate vote for conviction is a near-insurmountable barrier. This political reality shifts the primary function of impeachment. It becomes less a viable tool for removal and more a powerful mechanism for formal investigation, public exposure, and historical condemnation. The House's "sole Power of Impeachment" grants it unilateral authority to launch a formal inquiry, which carries greater constitutional weight than standard congressional oversight. This process, as demonstrated during the Watergate investigation that ultimately led to President Nixon's resignation, can compel testimony and evidence, creating an official, public record of wrongdoing.13 Even if a Senate conviction fails, the public hearings and the formal vote on articles of impeachment serve to legitimize the accusations, educate the public, and apply immense political pressure. The strategic value of impeachment, therefore, lies not only in the final vote but in the process itself, which functions as a constitutional tool for truth-finding and accountability, even when the ultimate sanction of removal is politically unattainable.

Section 1.2: The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: A Remedy for Presidential Inability

Ratified in 1967 in the wake of President John F. Kennedy's assassination, the 25th Amendment provides a clear procedure for addressing presidential disability and succession.14 While Sections 1-3 deal with presidential vacancy, vice-presidential vacancy, and voluntary transfers of power, Section 4 outlines a process for the involuntary removal of a president who is unable to perform their duties.

Constitutional Foundation and Process (Section 4)

Section 4, which has never been invoked, provides a complex and challenging process for circumstances where a president is deemed unable to serve but does not voluntarily step aside 14 :

Initiation: The Vice President and a majority of the "principal officers of the executive departments" (the Cabinet) must transmit a written declaration to the Speaker of the House and the President pro tempore of the Senate stating that the President is "unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office".15

Immediate Transfer of Power: Upon this declaration, the Vice President immediately assumes the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.14

Presidential Contest: The President can challenge this determination by sending their own written declaration to congressional leaders asserting that "no inability exists".15

Final Determination by Congress: If the President contests the finding, the Vice President and the Cabinet majority have four days to re-assert the President's inability in a second written declaration. If they do, Congress must assemble within 48 hours to decide the issue. A two-thirds vote in both the House and the Senate, to be held within 21 days, is required to affirm that the President is unable to serve, in which case the Vice President remains Acting President. If this high threshold is not met, the President resumes their powers and duties.15

The Standard: "Inability" vs. "Unfitness"

The crucial distinction between the 25th Amendment and impeachment lies in the standard for action. The amendment's language deliberately focuses on "inability".14 This term is widely understood to refer to a medical, physical, or mental incapacity that prevents the president from performing their duties. It is not intended as a remedy for political unfitness, criminal behavior, or abuse of power. Those forms of misconduct fall under the "high Crimes and Misdemeanors" standard of impeachment.

The distinct standards and high procedural bars of impeachment and the 25th Amendment create a dangerous constitutional vulnerability: a President who is profoundly unfit for office due to temperament, ideology, or authoritarian behavior, but is neither medically incapacitated nor politically abandoned by their party. The scenario of a leader who is actively malicious and power-hungry falls squarely into the "abuse of power" category for which impeachment is the appropriate constitutional tool.2 However, as noted, impeachment is likely to fail due to partisan loyalty. While the 25th Amendment might seem like an alternative, invoking it for purely political or behavioral reasons would be a constitutionally dubious and politically explosive act, likely to be perceived as a coup. Furthermore, the process relies on the cooperation of the Vice President and Cabinet—the very individuals appointed by the President and who, in a "cult" scenario, would be the least likely to act against him.14 Their loyalty serves as a nearly absolute firewall against the amendment's invocation. This reveals a critical gap: impeachment is the

correct tool for abuse of power but is politically fragile; the 25th Amendment is procedurally robust but applies to the wrong problem. An executive fitting the description of a "cult" leader could exploit this gap, being too politically protected for the former and not medically qualified for the latter, leaving the constitutional system without a direct, timely mechanism for removal.

Table 1: Comparison of Presidential Removal Mechanisms

Part II: Instruments of Executive Constraint

When formal removal from office is not immediately viable, the U.S. constitutional system provides a range of tools for the other branches of government to constrain, disrupt, and neutralize executive overreach. These instruments of power, held by Congress and the Judiciary, form the core of the checks and balances designed to prevent the concentration of unchecked authority in the executive branch.

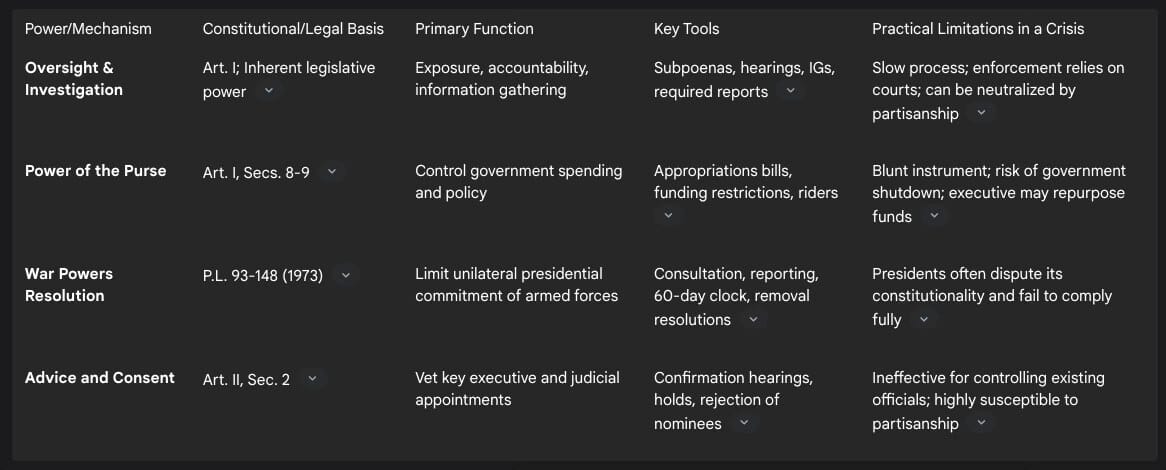

Section 2.1: Congressional Oversight: The Power of Investigation and Exposure

Beyond impeachment, Congress's most fundamental check on the executive is its power of oversight. This authority allows the legislative branch to review, monitor, and supervise federal agencies, programs, and policy implementation.19

While not explicitly enumerated in the Constitution, the power to conduct investigations is an inherent and essential aspect of Congress's legislative function under Article I.19 The Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed this power, describing it as "broad" and "as penetrating and far-reaching as the potential power to enact and appropriate under the Constitution".20 Key tools of oversight include:

Committee Hearings: Standing committees in both the House and Senate hold regular hearings to question executive branch officials, review agency performance, and investigate potential wrongdoing. These public forums are crucial for gathering information and exposing malfeasance to the public.19

Subpoena Power: Committees have the authority to issue subpoenas, which are legal orders compelling witnesses to testify or produce documents. This power applies to both government officials and private citizens and is a critical tool for forcing the disclosure of information that an administration may wish to conceal.20

Inspectors General (IGs): Congress has established independent IGs within most federal agencies. These officials are tasked with investigating waste, fraud, and abuse and are required to report their findings to both the agency head and Congress, providing a direct channel of internal accountability.19

Limitations and Challenges

Despite its breadth, congressional oversight faces significant limitations, especially when confronting a defiant executive:

Executive Privilege: A president can assert executive privilege to withhold information related to internal deliberations, leading to protracted legal battles that can delay investigations for years.20

Slow Enforcement: If the executive branch refuses to comply with a subpoena, Congress's recourse is to pursue enforcement through contempt proceedings or civil lawsuits. This process is slow, cumbersome, and ultimately relies on the judicial system, which the executive may also be challenging.20

Partisan Division: The effectiveness of oversight is highly dependent on the political landscape. When the president's party controls one or both chambers of Congress, committee chairs may be unwilling to launch meaningful investigations into the administration, effectively neutralizing this check on power.20

In a time-sensitive crisis involving an executive using "force," the fundamental asymmetry of speed between the branches becomes a critical weakness. Congressional oversight operates on a timeline of months and years, involving hearings, subpoenas, and court battles. In contrast, an executive determined to overreach can act unilaterally and immediately. This dynamic makes oversight an insufficient tool for halting a fast-moving crisis. The legal process to enforce a single subpoena can take years to resolve, as seen in cases like Trump v. Mazars.20 During this protracted period, the damage from unconstitutional orders or the misuse of agencies can be done long before oversight mechanisms yield a result. While essential for long-term accountability and building a case for impeachment, oversight is structurally ill-equipped to function as an emergency brake on a rogue executive; it is a tool for attrition, not rapid response.

Section 2.2: The Power of the Purse: The Legislative Branch's Ultimate Leverage

Arguably the most potent check Congress holds over the executive branch is its exclusive control over federal spending, commonly known as the "power of the purse".25

Article I of the Constitution grants Congress the sole power to levy taxes and appropriate funds, stating unequivocally, "No money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law".25 This gives Congress the ultimate leverage to shape and control the actions of the executive branch. Strategic applications of this power include:

Defunding Specific Actions: Congress can refuse to appropriate funds for specific agencies, programs, or personnel. This is a direct method to halt activities it deems improper, such as those carried out by the "gestapo like agencies" described in the query.25

Appropriations Riders: Congress can attach specific conditions, or "riders," to appropriations bills. These provisions can explicitly prohibit the use of funds for a particular purpose, such as implementing a controversial executive order.

The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974: Enacted after President Richard Nixon refused to spend funds appropriated by Congress for programs he opposed, this law establishes a formal process for budgetary matters and severely restricts the president's ability to unilaterally withhold funds. It requires the president to spend appropriated money unless Congress approves a request to rescind it.26

This power has been used to significant effect throughout U.S. history. For instance, Congress was instrumental in ending the Vietnam War by passing the Foreign Assistance Act of 1974, which cut off all military funding for the government of South Vietnam.25

The "Shutdown" Dilemma and the Fungibility of Funds

Despite its theoretical power, the power of the purse is often a blunt and politically risky instrument. Its most forceful applications, such as refusing to fund an entire department, can lead to a government shutdown, which inflicts widespread public harm and often results in a political backlash against Congress.28 This creates a high-stakes dilemma where legislators may be blamed for the consequences of exercising their constitutional authority. Furthermore, a determined executive can often find ways to circumvent congressional intent. The executive branch may attempt to repurpose funds from other accounts or declare a national emergency to unlock and reallocate funds for purposes not approved by Congress, as seen in disputes over funding for a border wall.27 This reveals a practical limitation: the power of the purse is most effective as a threat to force negotiation. When deployed against an executive willing to absorb the political damage of a shutdown or defy the spirit of appropriations law, it becomes a much weaker tool for immediate control.

Section 2.3: Judicial Review: The Courts as Arbiters of Legality

The judicial branch serves as a critical check on executive power by ensuring that its actions comply with the Constitution and federal law. This authority, known as judicial review, was famously established in the landmark 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison.32

Grounds for Invalidating Executive Action

Federal courts can review and strike down executive orders, regulations, and other agency actions on several grounds. An action can be invalidated if it:

Exceeds Presidential Authority: The action is not authorized by the Constitution or a congressional statute.29 The Supreme Court's decision inYoungstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952), which struck down President Truman's seizure of steel mills, is a key precedent establishing that presidential power is at its "lowest ebb" when acting in defiance of Congress.32

Violates the Constitution: The action infringes upon a specific constitutional right, such as freedom of speech or due process.32

Is Arbitrary and Capricious: Under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), courts can set aside agency actions found to be "arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law".34

Violates the Non-Delegation Doctrine: In rare cases, courts have struck down executive actions on the grounds that the underlying statute passed by Congress unconstitutionally delegated its legislative power to the president.32

The Enforcement Paradox

The judiciary's ultimate power to check the executive is constrained by a fundamental paradox: it depends entirely on the executive's voluntary submission to the rule of law. Courts do not have their own enforcement mechanisms; they cannot deploy marshals to arrest an agency head or the president for non-compliance.33 Instead, the enforcement of a court order against the executive branch relies on the executive branch's own Department of Justice.

In a scenario involving an executive who "ignor[es] courts of law," the judicial branch could be rendered impotent. If a court issues an injunction to block an unconstitutional order, a defiant president could simply direct the relevant agency to ignore the ruling. At that moment, the court's check is revealed to be a "parchment barrier," and the only remaining recourse is political—impeachment, congressional action, or public pressure—not legal. This creates a profound constitutional crisis, demonstrating that judicial authority is predicated on a shared constitutional norm that a rogue executive may have abandoned.

Table 2: Summary of Congressional Checks on the Executive

Part III: Countering the Misuse of State Force

A central concern in the scenario of a rogue executive is the potential use of the state's coercive apparatus—law enforcement and the military—for political ends. The American legal and constitutional system has erected specific firewalls to prevent this, though these barriers are not absolute. The ultimate check lies not in statutes alone, but in the constitutional obligations of the individuals who make up the chain of command.

Continue reading here (due to post length constraints): https://p4sc4l.substack.com/p/this-report-addresses-the-constitutional