- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- The Walters v. OpenAI case highlights the profound risks of misinformation in generative AI systems, especially when applied in legal or reputationally sensitive contexts.

The Walters v. OpenAI case highlights the profound risks of misinformation in generative AI systems, especially when applied in legal or reputationally sensitive contexts.

Most critically, for regulators, this case demonstrates the urgent need for enforceable standards for transparency, output verification, and harm mitigation in generative AI.

The Court Case Walters v. OpenAI: Misattribution, Hallucinations, and the Legal Boundaries of Generative AI

by ChatGPT-4o

Introduction

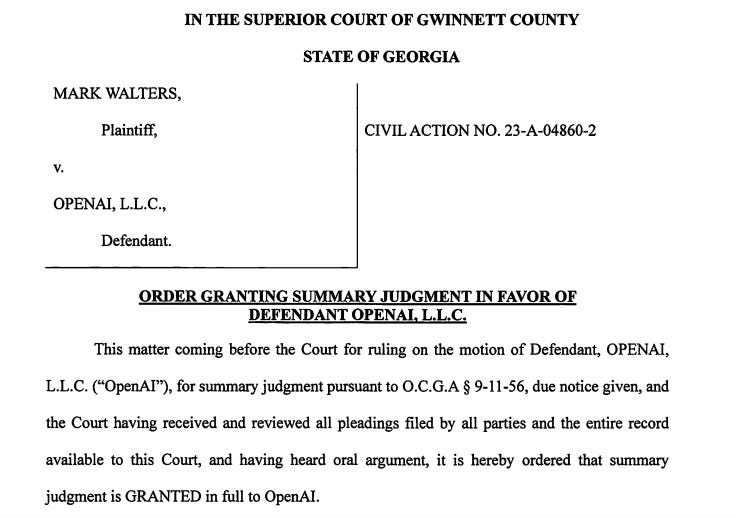

The case Walters v. OpenAI (23-A-04860-2, Gwinnett County, Georgia, May 2025) revolves around a core issue facing AI developers and users alike: the responsibility for false information generated by large language models (LLMs). At the heart of the case is a misattribution by ChatGPT of a fabricated legal complaint involving Mark Walters, a prominent Second Amendment commentator, which was mistakenly inserted into a summary of a real lawsuit. This case offers valuable insight into the risks of generative AI, the limitations of current disclaimers, and the responsibilities of both AI providers and users. It also raises important legal and ethical questions for developers, users, and policymakers alike.

The court ruled in favor of OpenAI, dismissing the defamation lawsuit filed by radio host Mark Walters. Judge Tracie Cason of the Gwinnett County Superior Court granted summary judgment to OpenAI on May 19, 2025, concluding that Walters failed to meet the legal standards required for a defamation claim.

Specifically, the court found that:

No Defamatory Meaning: The statements generated by ChatGPT could not be reasonably interpreted as factual assertions about Walters, especially considering the disclaimers provided by OpenAI and the context in which the information was presented.

Failure to Prove Fault: As a public figure, Walters was required to demonstrate that OpenAI acted with "actual malice"—knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth. The court determined that Walters did not provide sufficient evidence to meet this standard.

Lack of Damages: Walters was unable to show that he suffered actual harm from the incident. The false information was not published or disseminated beyond the initial interaction, and the individual who received the information did not believe it to be true.

This decision is significant as it addresses the challenges of applying traditional defamation law to AI-generated content. It underscores the importance of context, user awareness, and the role of disclaimers in evaluating the potential liability of AI developers for the outputs of their models.

Key Facts and Context

Mark Walters is a well-known radio host and author in the Second Amendment advocacy community.

On May 3, 2023, journalist Frederick Riehl asked ChatGPT to summarize a real lawsuit (SAF v. Ferguson) filed by the Second Amendment Foundation (SAF) against the Washington Attorney General.

Initially, ChatGPT correctly summarized pasted portions of the complaint.

When Riehl later provided a URL link to the complaint, ChatGPT erroneously stated that Walters was named as a defendant in the lawsuit and had been accused of fraud and embezzlement.

In reality, Walters had no connection whatsoever to the lawsuit, and the fabricated claims were entirely false.

Riehl did not publish this information but did raise the issue with OpenAI upon noticing the error.

Surprising, Controversial, and Valuable Statements

OpenAI’s Direct Acknowledgment of “Hallucinations”

OpenAI’s own documentation admits that “all major LLMs… are capable of generating information contradicting the source material,” known as hallucinations. This transparent concession is unusual in legal defenses, showing a clear acknowledgment of model limitations.Misattribution from a URL

Although ChatGPT correctly stated at first that it could not access the web, when Riehl re-entered the same URL, ChatGPT fabricated content it could not have accessed. This contradiction between its stated limitations and its behavior is both surprising and troubling.Riehl’s Prior Awareness of Hallucinations

Riehl was an experienced user of ChatGPT and acknowledged being aware that it could generate falsehoods. He had seen “flat-out fictional responses” in the past. This undercuts any negligence argument against OpenAI but raises the question of how much disclaimer is enough to absolve liability.Visible and Repetitive Disclaimers

The court notes that Riehl encountered multiple on-screen warnings that ChatGPT “may produce inaccurate information about people, places, or facts.” These were reiterated several times during his use, highlighting OpenAI’s legal strategy of consent-through-disclosure.No Publication, Yet Still Harm

Although Riehl never published the fabricated material, the case was still brought by Walters—likely on reputational and emotional grounds. This emphasizes that AI-generated misinformation can be legally and reputationally harmful even when unpublished.

Lessons for AI Makers

Disclaimers Are Necessary but Not Sufficient

While OpenAI had multiple disclaimers, this case illustrates that disclaimers may not shield developers from liability in all contexts—especially if hallucinations lead to real-world reputational harm.Limiting Functions Could Prevent Harm

If ChatGPT truly cannot access internet content via URL, it should consistently refuse to process such queries instead of attempting to fabricate summaries. Failure to align system behavior with stated limitations opens the door to legal scrutiny.Prompt Handling Needs Safeguards

Fabrications arising from URL-based prompts suggest a gap in prompt filtering or fallback behavior. AI developers must program LLMs to default to transparency when they cannot verify the accuracy of user-linked content.Legal Vulnerability Despite “Probabilistic” Language

The idea that outputs are “probabilistic” does not override the potential for defamation, misrepresentation, or emotional harm. AI makers must assess whether such legal disclaimers will stand up when harm is provable.

Lessons for AI Users

Human Review Is Not Optional

Even experienced users like Riehl were caught off guard by a hallucination. This underlines the importance of cross-checking AI outputs with verified sources before publication or dissemination.Liability May Still Arise

Although Riehl did not publish the false information, had he done so, both he and OpenAI could have faced defamation claims. Users must understand that the burden of verification ultimately rests with them.Awareness of Disclaimers Is Not a Legal Shield

Being aware that the system can “hallucinate” doesn’t eliminate responsibility. Users who rely on hallucinated outputs—even if warned—can still be seen as negligent if the results cause harm.

Disagreements and Concerns

There is one area in the court's reasoning—and by extension, OpenAI’s defense strategy—that warrants critique:

Over-reliance on Disclaimers as Legal Armor

The assumption that multiple disclaimers eliminate OpenAI’s liability is deeply problematic. If an AI is known to generate hallucinated information, especially when asked to summarize legal documents, then developers have a higher duty to introduce systemic constraints—not just warn users. Disclaimers shift responsibility to users, but hallucinations can arise without any ill intent or user negligence.

No Robust Error Prevention Mechanism

That ChatGPT fabricated serious criminal allegations about a real individual from a link it could not access raises serious technical and ethical questions. There appears to be no robust mechanism in place to prevent this kind of fabrication in sensitive domains like law, health, or finance.

Conclusion

The Walters v. OpenAI case highlights the profound risks of misinformation in generative AI systems, especially when applied in legal or reputationally sensitive contexts. While OpenAI attempted to protect itself through layered disclaimers and user agreements, the incident still demonstrates how hallucinations can cause tangible harm. AI developers must move beyond disclaimers and implement stronger safeguards—technical, legal, and procedural—to protect individuals from falsehoods.

For users, this case is a warning: always verify, never trust AI outputs blindly, and be prepared to shoulder responsibility if harm arises. Most critically, for regulators, this case demonstrates the urgent need for enforceable standards for transparency, output verification, and harm mitigation in generative AI.