- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- The Koda v. Suno case marks a defining moment for the music industry’s response to generative AI. It’s not merely a dispute over specific songs but a challenge to the opaque data practices...

The Koda v. Suno case marks a defining moment for the music industry’s response to generative AI. It’s not merely a dispute over specific songs but a challenge to the opaque data practices...

at the heart of AI development. The outcome will either validate the view that AI innovation can proceed under “fair use” — or reaffirm that artistic creation remains a licensed, consent-based domain.

AI’s Remix Revolution Meets Its Reckoning: Koda Takes Suno to Court

by ChatGPT-5

The Danish music rights group Koda has filed a landmark lawsuit against the U.S.-based AI music platform Suno, accusing it of training generative music models on copyrighted songs from Danish artists such as Aqua and MØ. The dispute represents a crucial flashpoint in the ongoing struggle between human creativity and artificial intelligence — and could reshape how copyright law applies to machine learning across Europe and beyond.

Koda alleges that Suno used its vast repertoire of protected works without authorization, while concealing the full scope and source of its training data. According to Koda, Suno’s generated music is capable of mimicking original artists so closely that it places AI-generated songs “in direct competition” with their human-made counterparts. Koda’s CEO, Gorm Arildsen, summarized the grievance bluntly: “Innovation can’t be built on stolen goods.”

This case echoes similar lawsuits filed in the U.S. by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) against Suno and Udio in 2024, but it is the first major European action to center on generative music and copyright. Koda’s complaint also goes beyond individual infringement claims — it calls for a new industry-wide standardfor consent, transparency, and remuneration in AI development. The organization warns that, if left unchecked, AI-generated music could cost the Danish music industry a “historic” 28% revenue loss by 2030.

🔍 Potential Consequences for Rights Holders

1. Precedent for European AI Training Cases

If successful, this lawsuit could establish a critical European precedent confirming that training AI models on copyrighted works without consent constitutes infringement, even if outputs are not exact reproductions. This would strengthen collective rights management organizations’ ability to pursue global claims.

2. Transparency and Data Disclosure Obligations

Courts may compel Suno and similar platforms to disclose training datasets and model provenance, setting a precedent that could force AI companies to reveal the full scope of their content ingestion. Such transparency could become a de facto regulatory standard ahead of EU AI Act enforcement in 2026.

3. Acceleration of Licensing Frameworks

The pressure of litigation could accelerate voluntary or mandatory licensing agreements between AI developers and music rights organizations — similar to recent deals between Universal Music and Udio. For rights holders, this could open new revenue streams from AI usage rather than continued defensive litigation.

4. Expansion to Other Creative Sectors

A favorable outcome for Koda would embolden other sectors — from book and news publishers to film studios — to pursue collective actions against AI developers. It could unify the creative industries around a shared licensing infrastructure or data-rights clearinghouse.

5. Economic and Cultural Safeguards

Koda’s prediction of a 28% revenue loss by 2030 underscores broader economic risks for smaller markets. A court victory could protect local artists and cultural industriesfrom being overshadowed by algorithmically produced content trained on their own works.

6. Global Pressure on “Fair Use” Defense

Since U.S. AI firms rely heavily on “fair use” as a legal shield, European rulings like this may undermine the legitimacy of that defense internationally, particularly in cross-border digital distribution. The outcome could influence U.S.–EU legal harmonizationand forthcoming AI copyright reform debates.

🎵 Conclusion

The Koda v. Suno case marks a defining moment for the music industry’s response to generative AI. It’s not merely a dispute over specific songs but a challenge to the opaque data practices at the heart of AI development. The outcome will either validate the view that AI innovation can proceed under “fair use” — or reaffirm that artistic creation remains a licensed, consent-based domain. For rights holders, this litigation could herald a new era of accountability — and perhaps the long-awaited blueprint for responsible AI in music.

To clarify:

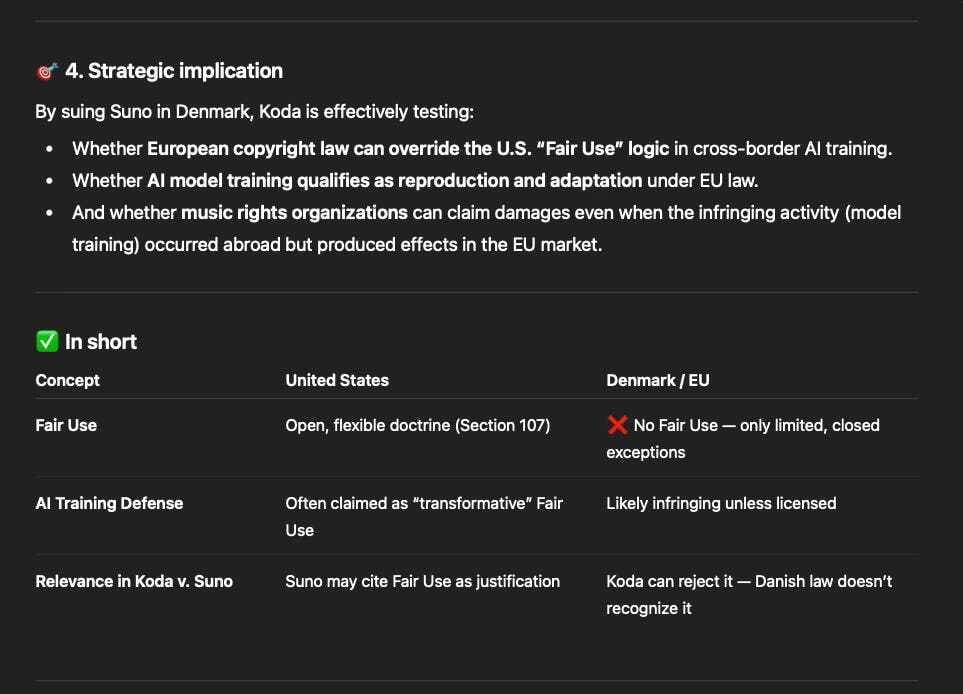

🇩🇰 1. Denmark does not have “Fair Use”

Denmark, like all EU member states, follows a closed system of copyright exceptions and limitations, not an open-ended fair use doctrine like the U.S. model.

Instead, Denmark implements EU Directive 2001/29/EC (the “InfoSoc Directive”), which specifies a finite list of permissible uses — such as quotation, teaching, parody, or private copying — under certain conditions. Anything notexplicitly allowed in that list is not lawful.

So while the U.S. copyright system uses Fair Use as a flexible balancing test (Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act), Denmark and other EU states operate under strict, enumerated exceptions. AI training on copyrighted music without consent is notamong those permitted exceptions.

⚖️ 2. Why “Fair Use” still matters — indirectly

Even though Denmark lacks Fair Use, it’s relevant because Suno is a U.S.-based company. Its defense strategy will likely rely on the same argument used in the ongoing RIAA v. Suno and Udio cases in the United States — that ingesting copyrighted material for model training constitutes transformative use and is therefore Fair Use under U.S. law.

However, once that same AI system outputs or distributes music in Europe (including Denmark), EU copyright law applies, and the Fair Use justification evaporates. Koda’s lawsuit therefore challenges the extraterritorial assumption that U.S. Fair Use protections can shield global AI companies operating across jurisdictions.

In other words:

“Fair Use” might protect Suno at home — but it won’t save it in Copenhagen.

🌍 3. Broader European context

The EU has only one limited AI-related copyright exception: Text and Data Mining (TDM), introduced in the 2019 DSM Directive (Articles 3 and 4).

However:

It’s not open-ended like Fair Use; it only covers reproductions “for the purposes of text and data mining.”

Rights holders can opt out (via machine-readable notices), which many collecting societies and publishers have already done.

That means training an AI on music—for creative or generative purposes—falls outsideboth the TDM exception and Danish copyright exemptions.