- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- The extensive and often opaque awarding of critical national infrastructure contracts, notably within the National Health Service and Ministry of Defence, to US technology firms such as Palantir...

The extensive and often opaque awarding of critical national infrastructure contracts, notably within the National Health Service and Ministry of Defence, to US technology firms such as Palantir...

...points towards a significant technological dependency with profound implications for UK data sovereignty and public service autonomy.

The Indelible Hand: Assessing the Trajectory of UK-US Alignment Under the Starmer Government

by “Gemini Advanced, Deep Research with 2.5 Pro.” Warning, LLMs may hallucinate!

I. Executive Summary

This report undertakes a comprehensive analysis of the evolving relationship between the United Kingdom and the United States under the government of Prime Minister Keir Starmer, specifically examining evidence that might indicate a deepening alignment or dependency approaching a de facto "51st State" dynamic. The investigation spans economic interactions, technological integration, geopolitical and security cooperation, and socio-political trends.

Recent trade negotiations, while yielding some sectoral benefits for the UK, reveal an asymmetrical dynamic where significant UK concessions have been made, particularly in the face of enduring US baseline tariffs and pressure regarding digital services taxes and agricultural access. The extensive and often opaque awarding of critical national infrastructure contracts, notably within the National Health Service and Ministry of Defence, to US technology firms such as Palantir, points towards a significant technological dependency with profound implications for UK data sovereignty and public service autonomy.

In foreign policy and defence, the UK's deep-rooted integration within US-led security architectures, exemplified by the Five Eyes intelligence alliance and further cemented by initiatives like AUKUS, demonstrates a continued, and arguably intensified, commitment to US strategic objectives. This alignment, while offering security benefits, inherently curtails independent strategic manoeuvre and locks the UK into long-term technological and geopolitical dependencies.

Socio-politically, a notable convergence in the tone and direction of immigration rhetoric and policy proposals between the Starmer government and contemporary US hardline approaches has been observed. While domestic political pressures within the UK are a significant driver, the parallelism contributes to perceptions of a shared trajectory. Similarly, in the crucial domain of Artificial Intelligence and copyright, US technological dominance and corporate influence, potentially amplified by think tanks with transatlantic ties, are likely to shape UK regulatory frameworks.

Collectively, these trends suggest a trajectory towards deeper UK integration with the US, characterized by an asymmetry where the UK often assumes an accommodating posture. While elements of strategic partnership endure, the balance appears to be shifting towards a more pronounced dependency. This report concludes by weighing the potential advantages of such a trajectory, such as economic opportunities and enhanced security, against the significant disadvantages, including the erosion of sovereignty, increased economic vulnerability, and constrained foreign policy. Ultimately, the analysis suggests that while some short-term or sectoral benefits may arise from closer US integration, the long-term risks to the UK's national interest, defined broadly to include policy autonomy and diversified international relationships, are substantial.

II. Introduction: The Shifting Anglo-American Axis – Towards a New Paradigm?

The relationship between the United Kingdom and the United States has long been a subject of intense scrutiny and varied interpretation. Often characterized by the evocative, if somewhat nebulous, term "special relationship," this transatlantic bond is currently navigating a period of significant global flux and domestic recalibration for both nations. Recent developments under the UK government led by Prime Minister Keir Starmer have prompted renewed questions about the nature and trajectory of this partnership, with some observers positing a trend towards an unprecedented level of integration, metaphorically described as the UK showing signs of becoming a "51st State" of the USA.

A. Deconstructing the "51st State" Hypothesis: From Rhetoric to Reality

The notion of the UK as a "51st State" is not intended as a literal prediction of political annexation. Rather, it serves as a provocative but potentially useful analytical framework to assess the degree to which the UK might be experiencing a significant and asymmetrical deepening of dependence on, and policy alignment with, the United States. This hypothesis suggests a dynamic where UK sovereignty and the capacity for independent action are perceptibly eroded in favour of conforming to or accommodating US strategic, economic, and political priorities. The term, while hyperbolic, captures underlying anxieties prevalent in some quarters about national autonomy, particularly in a post-Brexit Britain actively seeking to redefine its global role and forge new partnerships. The utility of this framework lies not in its literal interpretation, but in its capacity to focus critical attention on the quality, nature, and extent of US influence over UK policymaking. Such concerns often surface when a nation, historically a significant power in its own right, is perceived to be ceding undue influence to a larger, more dominant ally, especially when navigating new geopolitical and domestic vulnerabilities. The post-Brexit landscape, compelling the UK to seek robust international partnerships, with the US being a primary candidate, creates conditions where the terms of engagement and the balance of power within the relationship warrant close examination.

B. The Enduring "Special Relationship": Historical Context and Contemporary Pressures

The "special relationship" is rooted in a complex tapestry of shared history, language, democratic values, and, crucially, deeply interwoven defence and intelligence cooperation, extending back to the World Wars and solidified throughout the Cold War.1 This historical intimacy has fostered a unique, if not always symmetrical, partnership. The UK, for instance, has historically relied on US military technology, including for its nuclear deterrent, and is a core member of the US-led Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance.1 Academic analyses highlight that this relationship has oscillated between periods of profound cooperation and moments of divergence, shaped by evolving economic interdependencies and geopolitical shifts.2

However, this long-standing relationship is not static; it is continually reshaped by contemporary pressures. The UK's departure from the European Union (Brexit) has fundamentally altered its geopolitical calculus, removing it from a major trading and political bloc and arguably increasing its reliance on other key partners, most notably the US. Simultaneously, global dynamics such as the strategic challenge posed by China, the ongoing war in Ukraine, and the prospect of a more transactional or "America First" US foreign policy, particularly under administrations like that of Donald Trump, exert considerable influence on the terms of the Anglo-American engagement.1 These factors combined may be pushing the "special relationship" towards a configuration characterized by a more pronounced asymmetry of influence, where historical closeness could transition into a more dependent posture for the UK. The potential weakening of the UK's independent global leverage post-Brexit could make it more susceptible to the demands of a dominant partner, particularly if that partner prioritizes its own national interests in a starkly transactional manner.4

The government led by Keir Starmer assumed office facing a formidable array of foreign and economic policy challenges. Chief among these is the imperative to define the UK's global role in the aftermath of Brexit and to skillfully manage relations with key international partners, including a United States whose policy direction can exhibit significant shifts between administrations.3 Prime Minister Starmer has articulated clear ambitions for fostering economic growth and strengthening international partnerships.5 However, the pursuit of these goals, particularly a closer economic relationship with the US, occurs within a complex geopolitical environment.

Evidence suggests that the Starmer government is navigating a delicate balancing act. The pursuit of economic benefits through enhanced US trade is a clear priority, as evidenced by the positive framing of a recent trade deal as a significant achievement for British industry and jobs, and a reaffirmation of the special relationship under a US administration led by President Trump.12 Yet, this engagement is complicated by external pressures. For instance, Starmer's approach to UK-EU relations is reportedly cautious, partly influenced by the US President's historically negative stance towards the European Union.5 This dynamic suggests that US preferences can exert considerable influence on the UK's broader strategic choices. The imperative for post-Brexit economic "wins" might incline the government towards making concessions to secure agreements with the US, even if such terms are not entirely balanced. This scenario, where the UK is caught between the need for US partnership and the complexities of its European relationships, potentially amplifies US leverage over British strategic decision-making.

III. Economic Entanglement: Trade, Technology, and Tariffs

The economic dimension of the UK-US relationship is a critical arena for examining the "51st State" hypothesis. Developments in trade negotiations, the increasing integration of US technology into UK critical infrastructure, and the influence of US economic policy on UK autonomy offer significant indicators of the evolving power dynamics.

A. The New UK-US Trade Dynamics: A Partnership of Equals or Asymmetrical Concessions?

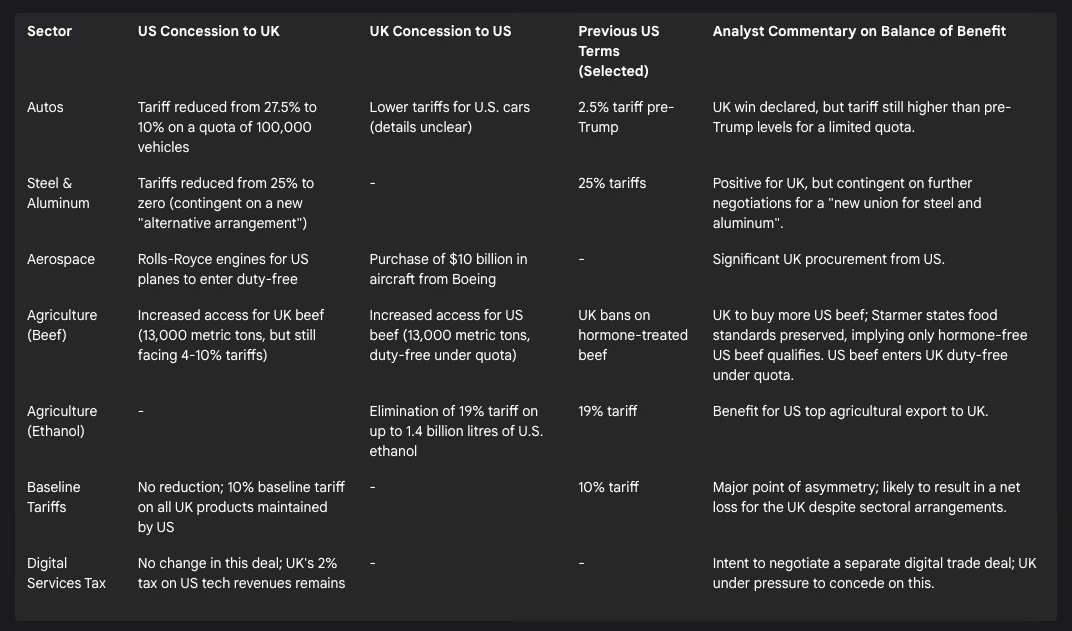

Recent trade agreements concluded under the Starmer government, while presented as beneficial for the UK, warrant close scrutiny regarding the balance of concessions. A "full and comprehensive" trade deal announced with the US, for example, involved the UK agreeing to purchase more American beef and ethanol and streamline its customs processes for US goods.9 In return, the US agreed to cut tariffs on UK autos (from 27.5% to 10% on a quota of 100,000 vehicles) and eliminate tariffs on UK steel and aluminum (from 25% to zero).9 While Prime Minister Starmer hailed this as a "great deal" protecting British jobs 9 , a deeper analysis suggests a more nuanced picture.

Crucially, the US administration refused to lower its baseline 10% tariff on all UK products, which impacts a significant volume of UK exports (worth $68 billion in the previous year).10 This retention of baseline tariffs is likely to result in a net negative impact on UK exports, despite the sectoral gains.10 Furthermore, the reduction in US auto tariffs to 10% for a limited quota is still considerably higher than the 2.5% tariff that was in place before the Trump administration's initial imposition of higher rates.10 The UK also committed to purchasing $10 billion in aircraft from Boeing, a significant US export.9

The following table summarizes key aspects of a recent trade framework agreement:

Table 1: Key Terms and Concessions in a Recent UK-US Trade Framework Agreement (under Starmer)

The pattern emerging from these negotiations suggests that the UK, eager for trade deals in its post-Brexit environment, may be operating from a position of lesser leverage. The US has demonstrated a willingness to employ tariffs aggressively 9 , and the UK appears to be making notable concessions, such as on agricultural imports and potentially on its digital services tax, to secure limited market access or to avert more damaging protectionist measures.11 This dynamic, where US economic power appears to dictate many of the terms, aligns with a model of dependency rather than a partnership of equals.

B. The Palantir Precedent and US Tech Dominance: Implications for UK Data Sovereignty and Public Services

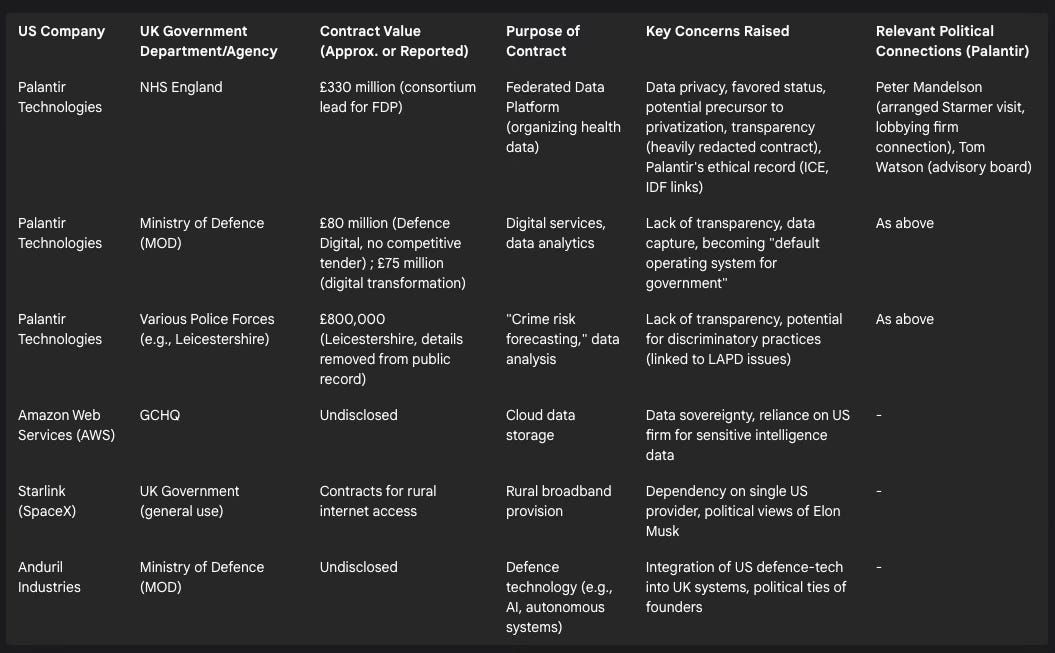

The increasing integration of US technology companies into the UK's critical national infrastructure, particularly in data management for public services, represents another significant area of potential dependency. The case of Palantir Technologies, a US data analytics firm, is particularly illustrative. Under the Starmer government, Palantir has been awarded a substantial £330 million consortium deal to deliver the NHS Federated Data Platform (FDP), a system designed to organize health data across NHS trusts.15 This contract, and others with the Ministry of Defence (MOD) (e.g., an £80 million contract for "Defence Digital" 16 , a £75 million contract for digital transformation 17 ) and police forces 17 , have been mired in controversy.

Concerns abound regarding data privacy, Palantir's favored status in contract awards, and the sheer lack of transparency, with significant portions of agreements, such as the FDP contract, being heavily redacted (three-quarters of its 586 pages were blacked out).15 Critics fear that such deals could be a precursor to the privatization of NHS data or services.15 Palantir's CEO, Alexander Karp, has made statements such as, "When the whole world is using Palantir... They'll have no choice," which do little to assuage fears about the company's long-term intentions and its potential to lock governments into its systems.17 The company's controversial history, including its work with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in tracking migrants and its reported links to discriminatory predictive policing programs, has also raised ethical alarms within the NHS and among privacy advocates.15

The involvement of influential political figures has further fueled these concerns. Peter Mandelson, a former Labour power broker and UK Ambassador to the US, reportedly arranged Prime Minister Starmer's visit to Palantir's headquarters; at the time, Palantir was a client of a lobbying firm founded by Mandelson.17 Former Labour peer Tom Watson has also taken a paid position on Palantir's public services advisory board.17

This integration extends beyond Palantir. Other major US tech companies are becoming deeply embedded in UK infrastructure: Elon Musk's Starlink provides satellite internet access in rural areas, the MOD has contracts with US defence-tech startup Anduril, and GCHQ, the UK's signals intelligence agency, struck a deal with Amazon for cloud data storage.18 This increasing reliance on US corporations for critical functions causes unease within parts of the UK intelligence community, particularly given the political ties and ideological leanings of some prominent US tech leaders.18

The extensive and often non-transparent awarding of these contracts signifies a potential shift towards profound technological dependency. This is not merely about procuring services; it involves embedding complex systems that could become indispensable, thereby granting US corporations significant operational leverage and access to vast quantities of sensitive UK data. This has undeniable implications for national sovereignty and the ability of the UK government to maintain autonomous control over its digital and physical infrastructure. The "lock-in" effect, where switching from these deeply integrated US systems becomes prohibitively complex or costly, mirrors a characteristic of dependency that aligns with the concerns underpinning the "51st State" hypothesis.

Table 2: Selected US Technology Contracts in UK Public Sector (Illustrative Examples, Focus on Palantir and others under Starmer Era)

The autonomy of UK domestic economic policymaking is facing direct challenges from US pressure, particularly in areas where UK policies diverge from US corporate or governmental preferences. A prime example is the UK's digital services tax, a 2% levy on the revenues of large technology companies, many of which are US-based.10 The US has consistently opposed such taxes internationally and has threatened retaliatory tariffs.11 Under the Starmer government, there are reports that UK negotiators are considering changes to this digital services tax, or its outright removal, as a concession to avoid broader US tariffs on British goods or to secure more favorable terms in a wider trade agreement.11 This potential backtracking on an established sovereign tax policy, designed to address perceived imbalances in how digital giants are taxed, would clearly demonstrate the significant economic leverage wielded by Washington.

Similarly, in trade negotiations, the issue of access for US agricultural products to the UK market remains a persistent US demand.9 While Prime Minister Starmer has insisted that UK food standards will not be lowered 9 , the agreement to purchase more US beef and ethanol 9 indicates a willingness to accommodate these demands. Historically, differences in food production standards (e.g., hormone-treated beef, chlorinated chicken) have been major sticking points, and any concessions, even with assurances, are viewed by critics as a potential weakening of UK regulatory autonomy under US pressure.

The influence is not always overt. Transatlantic think tanks, such as the Tony Blair Institute (TBI), are reportedly active in shaping UK government thinking, particularly on emerging policies like Artificial Intelligence and technology regulation.19 While such institutes can provide valuable expertise, their alignment with or promotion of US-led approaches could subtly steer UK policy towards convergence with American frameworks, potentially prioritizing innovation and corporate interests in line with the dominant US model.

Collectively, these instances suggest that the UK's capacity for independent economic policymaking is being tested. The willingness to negotiate away or modify domestic policies in response to US economic pressure or in pursuit of trade benefits indicates that UK economic decisions are increasingly intertwined with, and influenced by, the need to maintain a favorable relationship with its larger transatlantic partner. This dynamic potentially comes at the cost of domestic priorities or previously asserted sovereign rights in taxation and regulation.

IV. Geopolitical and Security Symbiosis: Alignment and Autonomy

The UK's geopolitical posture and its defence and security architecture are domains where the "special relationship" with the US has traditionally been most pronounced. An examination of foreign policy convergence, the deepening of defence and intelligence ties, and the overarching question of national sovereignty reveals a complex interplay between alliance benefits and the preservation of independent action.

A. Foreign Policy Convergence: The UK's Stance in a US-Influenced Global Order

Under the Starmer government, UK foreign policy decisions continue to exhibit a significant degree of alignment with US strategic positions, particularly concerning major global challenges such as the war in Ukraine and the strategic competition with China. For instance, in addressing the conflict in Ukraine, Prime Minister Starmer has been involved in developing a ceasefire plan in conjunction with France and Ukraine, with the explicit intention of presenting this plan to the United States and insisting on US backing and security guarantees.7 This approach, while collaborative with European partners, positions the US as the ultimate arbiter or key enabler for European security initiatives, underscoring a US-centric framework.

Regarding China, despite Prime Minister Starmer's past expressed concerns that the AUKUS security pact (discussed further below) could jeopardize the UK's commercial links with Beijing, his government has shown no inclination to withdraw from this US-led initiative.6 It has been observed that UK policy towards China often tends to mirror the "vicissitudes of the U.S. approach".6 Even where the UK might adopt a stance more aligned with European partners, such as on aspects of the Ukraine war that might differ from a potential Trump administration's approach, there is an acute awareness of potential "fierce American backlash" if similar divergence were to occur in its policy towards China.6 This suggests that US preferences and anticipated reactions act as significant constraints or guiding factors in the formulation of UK foreign policy.

The UK's commitment to NATO, described by Starmer as the "bedrock of our security," and its pledge to increase defence spending further solidify its alignment within the US-led Western security alliance.21 While the UK maintains its permanent seat on the UN Security Council and often takes a leading "penholder" role on certain international crises 21 , its capacity for truly independent manoeuvre on issues of core strategic importance to the US appears circumscribed. For example, while the UK has not used its UN Security Council veto since 1989 (a vote in alignment with the US and France against a resolution criticizing US actions in Panama) 21 , its general voting patterns and policy pronouncements often reflect a shared transatlantic outlook. A Security Council Monitor report from March 2025 noted a US-authored UN Security Council resolution on the Russia-Ukraine war (Resolution 2774) which exposed fractures among the P3 (France, UK, US) and highlighted Washington's evolving approach, omitting references to Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity in its initial General Assembly text, against which the US subsequently voted.22 While this specific instance points to US divergence from a unified P3 stance, the broader context of UK foreign policy often involves navigating US priorities carefully, as advised by think tanks like RUSI in the context of dealing with a Trump administration.8

Some political voices within the UK, such as Labour MP Clive Lewis, argue that the Prime Minister must make a definitive choice between the US and Europe, warning against deeper entanglement with what is described as a "deregulated, oligarch-driven capitalism embodied by figures like Elon Musk and driven politically by Maga-style populism" in the US, advocating instead for Europe as a more compatible partner.3 This highlights an internal debate about the direction and wisdom of continued close alignment with current US political and economic trends.

B. Deepening Defence and Intelligence Ties: AUKUS, Five Eyes, and the US Military Footprint in the UK

The UK's defence and intelligence apparatus is exceptionally deeply integrated with that of the United States, a relationship that continues to deepen under new strategic initiatives. The AUKUS pact, a trilateral security agreement between Australia, the UK, and the US, is a prime example. This pact involves the UK and US collaborating to provide Australia with nuclear-powered submarine technology and focuses on joint development of advanced military capabilities including hypersonic weapons, AI, and cyber warfare technologies.21 This multi-decade commitment not only locks the UK into a US-led security strategy for the Indo-Pacific but also reinforces its dependency on US defence technology, a reliance already evident in the UK's nuclear deterrent system, Trident, which utilizes US missile technology.1

Continue reading here (due to post length constraints): https://p4sc4l.substack.com/p/the-extensive-and-often-opaque-awarding