- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- The complaint is trying to turn a messy cultural argument (“training vs theft”) into a narrower systems argument: “you weren’t allowed to take the files, and you had to bypass controls to do it.”

The complaint is trying to turn a messy cultural argument (“training vs theft”) into a narrower systems argument: “you weren’t allowed to take the files, and you had to bypass controls to do it.”

Whether that move succeeds will depend on what discovery uncovers—and on how willing the court is to treat modern streaming architecture as a legally protected access regime under §1201.

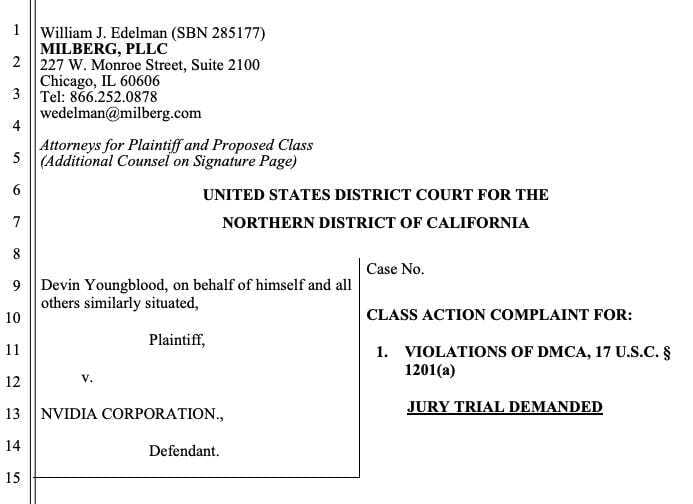

“Streaming Isn’t Scraping”: The Third Class Action Accusing NVIDIA of Mining YouTube to Train Cosmos

by ChatGPT-5.2

This new putative class action against NVIDIA is, at its core, a reframing move: instead of arguing only “you copied our videos,” it argues “you broke through access controlsto get file-level copies you weren’t allowed to have.” That matters because the complaint is built primarily around the DMCA’s anti-circumvention rule (17 U.S.C. § 1201(a)), which can create liability even before you get into traditional copyright questions like registration, substantial similarity, or fair use.

What the plaintiffs say NVIDIA did (the grievances)

1) File-level harvesting of YouTube videos at scale (not ordinary viewing).

The complaint draws a bright line between streaming inside YouTube’s controlled pathways and extracting durable copies of underlying audiovisual files for external use. The grievance is that NVIDIA allegedly obtained the latter “at the file level” through “scraping, bulk downloading, and other extraction methods,” then used those files to train and improve “Cosmos” (described as a foundational video model feeding multiple NVIDIA products).

2) Circumvention of YouTube’s technological protection measures (TPMs).

The legal theory is explicitly DMCA anti-circumvention: YouTube employs technical controls to limit bulk extraction and to keep users inside controlled streaming/offline-streaming features. Plaintiffs argue that at the scale required for modern video model training, getting training-ready copies necessarily means bypassing those controls.

3) No license/permission from creators for training use.

The class is defined as U.S. creators/rights-holders whose YouTube-hosted videos were allegedly accessed via circumvention and then used as training inputs. The complaint emphasizes creators’ ability to choose licensing pathways (including an “emerging market for AI training licenses”) and claims NVIDIA took that choice away.

4) Using “research” datasets as a roadmap to download copyrighted videos for commercial training.

A central factual pillar is NVIDIA’s alleged use of three YouTube-derived research datasets—HD-VG-130M, HDVILA-100M, and HowTo100M—which the complaint characterizes as lists of pointers (URLs/YouTube IDs and timestamps), not the underlying videos. Plaintiffs’ point: if you want to train on them, you must still download the actual YouTube files, and doing so at scale triggers circumvention/copying.

5) Building a “download-and-ingest” pipeline designed to evade enforcement.

This is where the complaint tries to sound like an internal incident report rather than a generic pleading: it alleges a pipeline involving 20–30 AWS virtual machines, aggressive download throughput, IP rotation to avoid blocks, and specific tooling such as yt-dlp for downloading and reconstructing audiovisual files.

The Law.com write-up highlights the same narrative: “bypass YouTube’s technical controls,” “20 to 30 virtual machines,” and “80 years worth” of videos per day.

Is the evidence any good?

It’s better than pure speculation, but it’s not yet the kind of evidence that wins on its own. Right now, it’s a plausible, technically coherent story anchored to a small number of allegations that will either be validated or collapse in discovery.

What’s strong (for a complaint stage)

Specificity about mechanisms. Naming a tool like yt-dlp, describing IP-rotation behavior on AWS, and talking about URL databases/“download pipelines” is more concrete than the usual “they scraped the internet” complaint language. It gives the court a believable pathway from YouTube IDs → file-level copies → training corpus.

The “pointers not files” logic. The complaint’s explanation that these datasets are essentially roadmaps (IDs/timestamps) is strategically smart because it forces the reader to confront the missing step: someone still had to download the videos.

DMCA positioning reduces dependence on copyright registration and fair-use fights. Plaintiffs explicitly argue that §1201 doesn’t hinge on whether the underlying works were registered—useful for YouTube creators, many of whom won’t have registrations.

What’s weak / vulnerable

A lot is “information and belief,” relying on “leaked internal communications” reported by media. The complaint repeatedly rests on public reporting about internal Slack chats/emails. That can be enough to plead, but it becomes fragile if the underlying materials can’t be authenticated or don’t say what plaintiffs imply.

The hardest legal hinge: do YouTube’s measures qualify as “effective technological measures” controlling “access” under §1201? Plaintiffs assert YouTube’s controls qualify; NVIDIA will likely argue users already have access (they can watch) and that this is really about copying not access, or about breaching contract/TOS rather than “circumvention.” Courts have split over how far §1201 reaches when the work is publicly streamable but not downloadable in durable form. The complaint is clearly drafted to win that conceptual battle (“streaming vs possession”), but it’s still a litigation risk.

Scale claims invite proportional proof. “Millions of videos,” “80 years per day,” “human lifetime of visual experience per day” are rhetorically powerful, but they are also audit invitations. If discovery shows lower scale, less permanence, different tooling, or licensed sources for key parts, the headline narrative loses force.

Net assessment: At the pleading stage, the evidence is credible enough to get into court and survive early dismissal on “they’re just guessing,” but the case’s staying power will depend on whether plaintiffs can obtain (and authenticate) logs, dataset build records, vendor contracts, internal approvals, and model-training lineage that show systematic file-level downloading and circumvention.

The most surprising, controversial, and valuable statements

Below are the statements doing the most strategic work in the complaint (and why they matter).

Surprising

The “clip-by-clip = multiple violations” framing. Because datasets are timestamped clips, the complaint argues repeated retrieval/duplication of the same underlying video may occur to extract different segments—turning one video into multiple acts of copying/circumvention. This is a clever attempt to scale statutory damages logic to the technical structure of modern video datasets.

The allegation that datasets were curated to exclude creator names/watermarks. Plaintiffs claim one dataset intentionally selected high “aesthetic” content while excluding visible creator names/watermarks—suggesting a pipeline optimized to extract “clean” training material. If true, it’s narratively devastating because it implies intent to strip provenance rather than incidental scraping.

Controversial

“Streaming is not access to the file.” The complaint’s core rhetorical engine is that YouTube “affirmatively withholds” the audiovisual data files from public download, so mass downloading is “unauthorized access,” not merely copying something publicly available. This is exactly where courts may disagree: the boundary between “access” and “use/copy” in a streaming world is one of the most contested issues in §1201 litigation.

The “umbrella approval / executive decision” allegation. Plaintiffs cite leaked communications suggesting that when employees asked about legal approval, management replied it was an “executive decision” with “umbrella approval” to use “all of the data.” If discovery supports this, it pushes the case toward willfulness; if it doesn’t, it risks looking like sensational pleading.

Valuable (for understanding where AI copyright fights are going)

The complaint treats “TPM circumvention” as the enforcement choke point for AI training. This is arguably the most strategically important move: plaintiffs are betting that the cleanest, least fair-use-dependent path is to prove bypass of technical controls rather than to litigate whether training is transformative. If this theory gains traction, it encourages platforms and publishers to invest in more clearly “effective” access controls because those controls become legally salient.

The “datasets are pointers” theory is a broader indictment of the research-to-commercial pipeline. It highlights a recurring pattern: research datasets built from platform content circulate widely; commercial actors then operationalize them by performing the downloading step at industrial scale. That story—research norms + weak enforcement + massive commercial incentive—may be the next major fault line in AI training governance.

The market narrative: creators’ lost ability to license AI training. Plaintiffs explicitly argue harm as loss of control over downstream licensing markets, not just “my video got copied.” That’s a sign of where damages arguments are heading: control, provenance, and licensing markets as the “property interest,” not just traditional infringement harms.

Why this case matters beyond NVIDIA

The Law.com coverage notes this is described as NVIDIA’s third putative class action in this vein and that another case remains ongoing, reflecting a growing pattern of YouTube-origin training disputes.

But the deeper significance is doctrinal: if plaintiffs can successfully characterize large-scale training-data acquisition as “circumvention of access controls,”then AI training litigation shifts from the endless fair-use trench warfare toward a more infrastructure-centered conflict about technical gating, platform controls, and “file-level” boundaries.

In other words, the complaint is trying to turn a messy cultural argument (“training vs theft”) into a narrower systems argument: “you weren’t allowed to take the files, and you had to bypass controls to do it.” Whether that move succeeds will depend on what discovery uncovers—and on how willing the court is to treat modern streaming architecture as a legally protected access regime under §1201.