- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

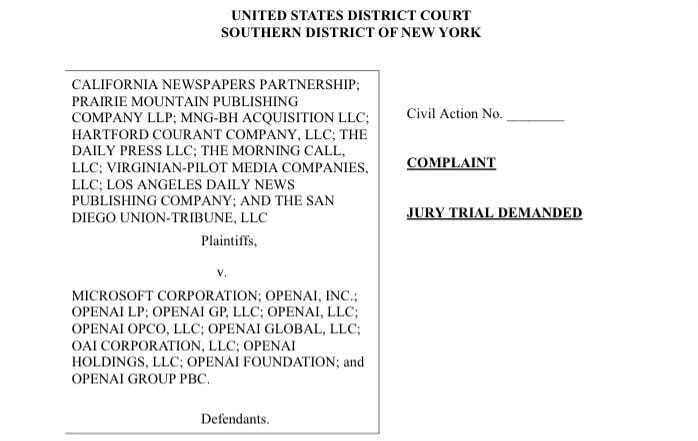

- The complaint filed by the California Newspapers Partnership and a broad coalition of regional publishers against Microsoft and OpenAI marks one of the most aggressive and unambiguous challenges yet.

The complaint filed by the California Newspapers Partnership and a broad coalition of regional publishers against Microsoft and OpenAI marks one of the most aggressive and unambiguous challenges yet.

(1) framing harm as misappropriation & derivative-market destruction, (2) invoking constitutional language around Congress’s duty to protect authors, (3) model updates as repeated acts of copying.

The Newspapers’ Case Against Microsoft & OpenAI — Evidence, Grievances, and Strategic Implications

by ChatGPT-5.1

The complaint filed by the California Newspapers Partnership and a broad coalition of regional publishers against Microsoft and OpenAI marks one of the most aggressive and unambiguous challenges yet to the legality of generative AI training on copyrighted news content. The case builds upon prior filings by the New York Times, book authors, visual artists, and music rightsholders, but the publishers here make three strategic moves: (1) framing the harm as ongoing misappropriation plus derivative-market destruction, (2) invoking constitutional language around Congress’s duty to protect authors, and (3) framing model updates as repeated acts of copying. All three create a more potent narrative and a potentially stronger claim to statutory damages.

This essay reviews the major grievances, evaluates the quality of the evidence presented, highlights the most surprising or controversial statements, and concludes with an assessment of plaintiffs’ chances alongside concrete recommendations for Microsoft and OpenAI.

1. Plaintiffs’ Core Grievances

The complaint outlines several interconnected allegations:

1.1. Unlawful copying of copyrighted news articles for training

The plaintiffs assert that Microsoft and OpenAI “systematically copied, stored, and used” their articles without authorization to train GPT models, which the complaint claims is not transformative and is instead a massive commercial use intended to replace the need for news consumption. This framing is consistent with earlier litigation but is made more specific here by repeatedly emphasizing the value of local reporting and the economic fragility of regional newspapers.

1.2. Derivative market harm and substitution

The complaint argues that AI systems using plaintiffs’ content “reduce consumer visits, reduce attribution, and reduce monetization opportunities,” thereby harming the derivative and licensing markets for news. This is aligned with arguments made by Getty and NYT but is presented more explicitly as a structural threat to journalism.

1.3. Continuous new infringements through model updates

A distinctive grievance is that each iteration of GPT, including fine-tuning, creates “new unauthorized copies,” implying a rolling set of infringements accruing statutory damages for each update. This is highlighted prominently in the early pages of the complaint, where plaintiffs argue that updating a model “requires the Defendants to store, reprocess, and reuse the copyrighted content again and again”.

1.4. Failure to honor robots.txt and other opt-out signals

The complaint alleges that the defendants ingested content obtained through scraping that violated the publishers’ access restrictions. While the technical evidence is not fully presented in the first pages, the complaint asserts that indicators in the training corpus “clearly show” inclusion of protected works.

1.5. Public admissions by OpenAI leadership

The complaint heavily relies on Sam Altman’s testimony to the British House of Lords, where he acknowledged that training LLMs without copyrighted works would “not be able to build” a competitive model—a statement quoted nearly verbatim in the Nature of the Action section.

2. Quality of Evidence Presented

While the complaint is still at the pleadings stage, several types of evidence stand out:

2.1. Strong evidence

Admissions by OpenAI: The complaint leans on Altman’s statements and prior admissions in other lawsuits. These are legally significant because they acknowledge both (1) the use of copyrighted content, and (2) the centrality of that content for model performance.

Structured legal theory of repeated infringement: The idea that each update constitutes a new infringing reproduction is a sophisticated reframing that courts have not yet ruled on directly but is grounded in traditional copyright principles.

2.2. Moderate quality evidence

Assertions regarding robots.txt violations: The complaint states that indicators show content was scraped, but does not provide technical exhibits in the first pages. Without logs, crawler behavior records, or dataset-provenance documentation, this remains an allegation that will require discovery to substantiate.

Claims of market substitution: While plausible, the complaint will need empirical data demonstrating traffic decline due to AI systems. The current filing asserts harm but does not yet present econometric evidence.

2.3. Weakest evidence

Assumptions about model internals: Assertions that “copies of copyrighted works reside within the model” may be challenged unless plaintiffs provide forensic model-extraction evidence. Courts so far have not accepted this claim without strong technical proof.

Overall, the strongest parts of the complaint rely not on technical proofs but on defendants’ own statements and the economic logic of copyright.

3. Most Surprising, Controversial, and Valuable Statements

Surprising

The categorization of each model update as a new act of infringement: This approach multiplies potential damages significantly and could redefine the liability landscape for all AI companies.

Explicit reference to constitutional obligations under Article I, Section 8 to protect authors, framing the case as a failure of the constitutional copyright bargain rather than a simple statutory infringement claim.

Controversial

Implicit claim that generative AI systems are “competing” as news sources, thereby substituting for journalism itself.

The idea that AI training constitutes “publishing” under copyright law, an unconventional but rhetorically powerful framing.

Valuable

The articulation of a “copyright management infrastructure” that the plaintiffs argue has been undermined: This is particularly important because it reframes the case as not merely about copying, but about interference with an entire rights ecosystem—the exact argument that courts tend to take seriously in DMCA §1202 claims.

The emphasis on regional news as a fragile public good, likely to resonate with judges and juries.

4. Likelihood of Success

Copyright infringement (reproduction right): High probability of surviving a motion to dismiss

The plaintiffs’ allegations are aligned with those that have already survived early motions in NYT v. OpenAI and the authors’ cases.

DMCA §1202 claims (removal/alteration of rights-management information): Moderate probability

Courts require evidence of actual removal of metadata. The complaint asserts this but does not yet produce detailed forensic exhibits.

Market harm and damages: Moderate, but with large upside if successful

If the plaintiffs can demonstrate:

traffic displacement,

unlicensed derivative use,

and real economic loss,

they may secure substantial damages. The “each update is a new infringement” argument could be transformative.

Overall assessment

The case has strong legs, especially given:

public statements by OpenAI leadership,

a political climate increasingly attentive to publisher consent,

and growing judicial skepticism toward “fair use at scale.”

Plaintiffs are well-positioned to secure either (1) a meaningful settlement, or (2) a favorable ruling on at least some claims.

5. Recommendations for Microsoft and OpenAI

To avoid repeating these conflicts and mitigate future litigation risk, several strategic steps are essential:

5.1. Implement verifiable provenance and dataset logging

Full documentation of:

where training data comes from,

crawler behavior logs,

permissions collected,

will be critical for future legal defenses and regulatory compliance.

5.2. Shift to first-party and licensed corpora

Build “clean rooms” of:

licensed journalism,

purchased archives,

public-domain and CC-BY works,

and stop claiming that scraped web data alone is viable.

5.3. Deploy publisher-controlled access mechanisms

Respect:

robots.txt,

TDM-reservation signals (EU),

industry opt-out registries (STM, IPTC).

Implement technical enforcement through hash-based exclusion lists.

5.4. Introduce publisher revenue-sharing and licensing ecosystems

The future equilibrium will likely resemble:

blanket licensing (ASCAP-style for text),

pay-per-token compensation,

structured data APIs for newsrooms.

Better to build this proactively.

5.5. Create safer model architectures

Reduce legal exposure by:

minimizing memorization through architectural design,

developing automated detection of verbatim reproduction,

building layered re-training mechanisms that preserve knowledge while removing specific works.

5.6. Publicly disclose model training composition

A transparency regime—subject to trade secret protection—would dramatically reduce suspicion and litigation.

Conclusion

This complaint is among the most sophisticated and aggressive news-publisher suits brought against AI firms to date. It leverages defendants’ own admissions, introduces new theories of repeated infringement, and positions regional journalism as a public good harmed by unlicensed AI training.

While not all claims are ironclad, the plaintiffs have substantial likelihood of success on core copyright allegations. If Microsoft and OpenAI continue relying on opaque web-scraped datasets without licensing or transparent provenance, similar lawsuits will proliferate. The clear path forward is a licensing-first strategy, robust provenance documentation, stronger opt-out compliance, and architectural safeguards to minimize unauthorized reproduction.

This case should be a turning point—not only for the defendants but for the entire generative AI industry.