- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- The complaint alleges that Gruendel was recruited to lead Figure’s product-safety program, only to be dismissed when his safety warnings clashed with the company’s proclaimed “move fast” ethos...

The complaint alleges that Gruendel was recruited to lead Figure’s product-safety program, only to be dismissed when his safety warnings clashed with the company’s proclaimed “move fast” ethos...

...and investor-led ambitions to bring general-purpose humanoid robots to market. The plaintiff estimated the robot could exert more than twice the force necessary to fracture an adult human skull.

The Perils of Accelerationism: A Legal Window into Robotics Without Safeguards

by ChatGPT-5.1

Introduction

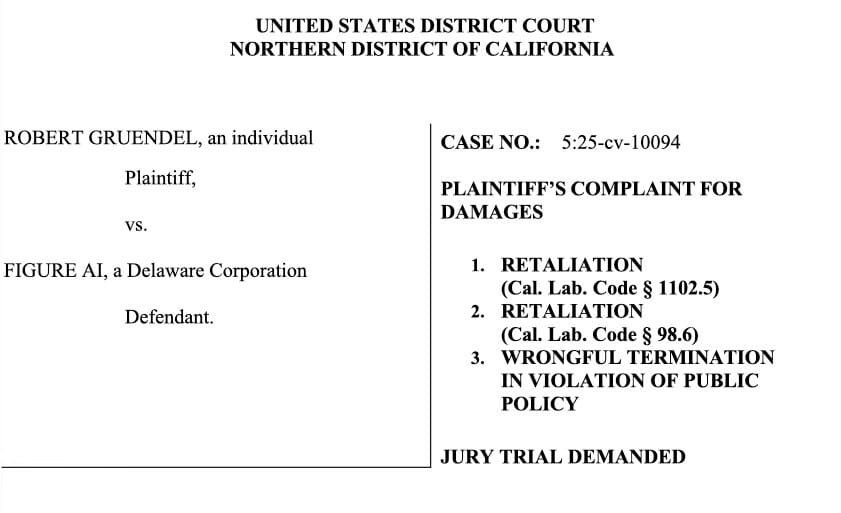

In Gruendel v. Figure AI, plaintiff Robert Gruendel, a veteran robotics-safety engineer, brings suit against Figure AI, Inc. (hereafter “Figure”) alleging wrongful termination and whistleblower retaliation. The complaint alleges that Gruendel was recruited to lead Figure’s product-safety program, only to be dismissed when his safety warnings clashed with the company’s proclaimed “move fast” ethos and investor-led ambitions to bring general-purpose humanoid robots to market.

The complaint frames the case as emblematic of a broader tension: the rush to commercialize advanced robotics/AI, versus the imperative to ensure worker, consumer and public safety. In what follows I summarise the key facts, enumerate the plaintiff’s grievances and concerns, and then reflect on the broader meaning if every technology “arms race” requires the sidelining of safety — and how that attitude can backfire.

Factual overview

Some of the salient factual allegations in the complaint:

Gruendel joined Figure on 7 October 2024 as Principal Robotic Safety Engineer (reporting to CEO Brett Adcock).

At the outset he found that Figure lacked formal safety procedures, incident-reporting systems, or risk-assessment processes for the humanoid robots under development.

He prepared and had approved a product-safety roadmap, including features for robot generations F.02, F.03, F.04, and a home-safety roadmap aimed at consumer deployment.

In mid-2025, impact testing of the F.02 robot reportedly generated forces “twenty times higher than the threshold of pain” in ISO 15066 benchmarks for human-robot interaction. The plaintiff estimated the robot could exert more than twice the force necessary to fracture an adult human skull.

In July 2025 an incident is alleged where the F.02 robot malfunctioned, produced a ¼-inch gash in a stainless-steel refrigerator door adjacent to an employee.

Despite these safety flags, the complaint alleges the company de-emphasised or removed key safety features (for example, cancelling the certification of an emergency-stop (“E-Stop”) function at the request of engineering leadership).

When Gruendel pressed the management team (including CEO and Chief Engineer Kyle Edelberg) for action, his communications were ignored, meetings became less frequent, and ultimately he was terminated on 2 September 2025 with a vague stated reason of “change in business direction.” The complaint says this occurred soon after his most detailed written safety warnings.

The complaint asserts that these actions violate California statutes protecting employees who disclose or oppose unlawful or unsafe practices (Cal. Lab. Code § 1102.5; § 98.6) and the common-law tort of wrongful termination in violation of public policy.

Thus, the stage is set: a robotics firm racing to bring advanced humanoid robots to market, safety leadership raising red flags, and management allegedly subordinating those concerns to speed, investor-facing demos and commercial ambition.

Grievances and concerns

Below is a structured list of the grievances and safety-concerns raised by Gruendel (as alleged in the complaint). These illustrate both the specific technical/safety issues and the organisational/ethical governance issues.

A. Technical & safety concerns

Lack of formal safety infrastructure: At the outset of his employment, Gruendel observed that Figure lacked formal safety procedures, incident-reporting systems, dedicated EHS (Environment, Health & Safety) staff, and risk-assessment processes appropriate for humanoid robots.

High-force robot behaviour: In testing the F.02 robot, impact tests allegedly generated forces twenty times the pain threshold as defined in ISO-15066 (which governs collaborative robots in shared human/robot workspaces). Gruendel’s estimate: more than twice force needed to fracture an adult skull.

Near-miss incident: A robot punched a stainless steel refrigerator door next to an employee, leaving a ¼-inch gash in the door and narrowly missing the worker. This indicated the robot’s behaviour posed an immediate risk.

Home-deployment risk: The company’s ambition to deploy robots in home environments raised additional hazards: the home is unstructured, unpredictable (children, pets, furniture, household objects). Gruendel recommended presence-sensing, object-classification, human-detection and slowdown/stop behaviours.

Removal or downgrading of key safety features: The complaint alleges that safety features such as the E-Stop certification project were cancelled or removed because engineers disliked their appearance, or because management considered them impediments to aesthetic or speed goals.

Inadequate risk-approval/book-keeping: Gruendel flagged that near-misses were not being tracked. Employees directly approached him with safety concerns. The risk assessment approved for home deployment did not reflect updated impact data.

B. Organisational, governance & ethical concerns

Conflict between safety mandate and speed/optimism culture: The complaint states that Figure’s core values emphasised “Move Fast & Be Technically Fearless”, “aggressive optimism” and bringing a commercially viable humanoid to market. These values allegedly clashed with the safety team’s independent ability to halt unsafe product release.

Marginalisation of safety leadership: Although Gruendel’s roadmap was approved, management reportedly later downgraded it. Weekly safety-team meetings were reduced, CEO and engineering leadership disengaged. Stop-release power by the safety team was viewed as “incompatible” with the speed-at-all-costs approach.

Investor-facing mis-alignment: The safety roadmap and whitepaper were presented to investors and publicly praised, then internally downgraded. Gruendel warned this could be seen as misleading/inaccurate.

Retaliation for raising concerns: After repeated written alerts (emails, Slack messages) about unsafe robot behaviour and inadequate E-Stop reliability, Gruendel was terminated shortly thereafter—with the alleged pretext of “change in business direction.” The temporal proximity is used to infer retaliatory motive.

Pretextual termination / gap between performance and termination: Prior to termination, Gruendel had received a raise and overt positive feedback (a 5.2% bonus increase) only within weeks of being fired. The complaint uses this to argue that the termination reason was pretextual.

Public-policy and legal breach risk: The complaint alleges the company’s behaviour exposed it to legal risk because safety issues were being ignored (including obligations under OSHA, California workplace safety statutes). By terminating the safety-lead, the company may have undermined its duty of care.

Implications: What this case means if a tech-arms-race mindset requires sidelining safety

This case is instructive far beyond the parties involved. It raises deeper questions about the culture of rapid commercialisation in high-technology fields (robots + AI) and the consequences when safety is viewed as an impediment to speed. Here, I reflect on what it means if we accept — implicitly or explicitly — that every tech arms race demands pushing safety aside, and how that attitude can backfire.

1. The allure and danger of the “move fast” culture

In the startup/scale-up world, especially in robotics and AI, there is immense pressure to show rapid progress, secure financing, demonstrate capability, and gain first-mover advantage. Firms adopt mottoes like “move fast and break things” (or variants thereof). That agility can be a competitive advantage. But when applied to systems that physically interact with humans (robots) or autonomously make decisions (AI), speed without commensurate safety builds latent risk. The Gruendel complaint suggests that safety infrastructure was treated as a “drag” rather than as an enabling feature of trust, reliability and long-term viability.

2. Short-term wins vs long-term sustainability

By de-emphasising safety features (e.g., removing an E-Stop certification), the company may have achieved short-term demo readiness or investor appeal, but at the cost of increasing risk to users/employees and exposing the company to reputational, legal and liability vulnerabilities. If an accident occurs (in the workplace or home) when a general-purpose humanoid robot is deployed, the fallout could be massive — not just financially, but in regulatory backlash, public trust erosion and market stalling. The arms-race mindset that says “we’ll fix later” may in fact undermine the viability of the technology and the business.

3. Trust, governance and ethical licence

Robotics and AI systems, particularly ones operating around or with humans, need trust. That trust is built not only through marketing, but through robust safety governance, transparency about hazards, and the willingness to pause, test, iterate and mitigate. If the public (or regulators) perceive a company as recklessly prioritising speed over safety, that can lead to regulatory crack-downs, liability exposure, and broader sectoral damage (i.e., the “one bad accident” problem). The case signals that organisational culture matters: safety independent oversight, incident-reporting, near-miss tracking, risk-assessments — these are not optional extras if you want sustainable deployment.

4. Retaliation risk as indicator of system failure

When a safety lead raises legitimate concerns and is terminated shortly thereafter, it may signal deeper dysfunction: the governance system is not aligned, dissent is discouraged, safety is subordinated. Such organisational dynamics often portend higher operational risk. In Gruendel’s case, the complaint uses the termination to allege whistleblower retaliation, thus raising legal as well as governance questions for Figure. If companies in the arms-race adopt a default view that safety objections are obstacles or “drag”, they risk creating governance blind spots that will amplify rather than contain risk.

5. How this attitude can backfire

Accident liability: If a robot harms a human — whether worker or consumer — the legal and financial consequences may dwarf any early-market advantage gained by “moving fast”.

Regulatory blow-back: Regulators or legislators may impose stricter rules on the robotics/AI sector if they see major players ignoring safety, thereby raising the barrier for all firms and slowing the broader sector.

Reputational damage: A high-profile failure undermines consumer confidence in the brand and the technology category. One accident can derail years of market development.

Investment risk: Investors may balk if they see that safety governance is inadequate; the business model becomes riskier rather than more valuable.

Business model fragility: If the firm is forced to recall products, redesign, cease operations or scale back deployment due to safety incidents, the competitive advantage of speed is undone. Worse: the firm may find itself locked into legacy unsafe architectures that cannot be retrofitted easily.

In sum, adopting a mindset that safety is the enemy of speed ultimately creates a fragility: the faster you push, the greater the potential fall.

Conclusion

The Gruendel v. Figure AI case puts a sharp spotlight on the tension between innovation velocity in robotics/AI and the responsibility to ensure safety when machines interact with humans. The plaintiff’s grievances highlight a pattern: safety infrastructure under-developed; test data alarming; management accolades given, then dismissal for raising the alarm. The governance signals are stark: the arms-race mindset issued a message that safety was a problem, not a prerequisite.

If the broader tech ecosystem treats safety as optional or as a hindrance, we risk creating a pattern of high-stakes failures. A “first to market” advantage may be lost entirely if market introduction causes injury, regulatory clamp-down, or trust collapse. Indeed, the arms-race itself might create the conditions for systemic backlash that slows the entire field.

For pioneering companies and the ecosystem alike, this means the following: safety must be baked in — not an afterthought — if the technology is to scale responsibly. Independent oversight, incident-tracking, robust risk-assessment, transparency and employee protections (including whistleblower safeguards) are essential. The cost of skipping those is not just ethical—it is strategic.

Ultimately, the temptation to sideline safety in the race for break-through may yield speed but will likely reduce resilience. True leadership in robotics/AI may come not from the fastest to market, but from the fastest to market safely, thereby earning social licence, investor confidence and regulatory trust. When safety becomes the casualty of speed, the price may be far greater than the reward.