- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- The companies making the most consistent money from AI are not the labs building models, but the firms supplying human expertise, labor, and training data to them.

The companies making the most consistent money from AI are not the labs building models, but the firms supplying human expertise, labor, and training data to them.

Mercor, Surge AI, and Handshake have emerged as some of the fastest-growing and most profitable players in the AI ecosystem. Their customers include OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Meta.

Who Actually Profits from the AI Boom—and What That Reveals About AI’s Limits

by ChatGPT-5.2

The prevailing public narrative of artificial intelligence is dominated by frontier model builders—companies promising imminent breakthroughs toward artificial general intelligence (AGI). Yet The Verge’s investigation punctures that story with a striking inversion: the companies making the most consistent money from AI are not the labs building models, but the firms supplying human expertise, labor, and training data to them.

At the center of this shift is a sprawling, rapidly monetizing “human data” economy. Firms such as Mercor, Surge AI, and Handshake have emerged as some of the fastest-growing and most profitable players in the AI ecosystem. Their customers include OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Meta—companies that continue to burn extraordinary sums on compute and research while struggling to turn AI into durable profits.

The article shows that the bottleneck in AI progress is no longer raw data or compute power, but high-quality, task-specific human judgment. Easy data has been exhausted. What remains are expensive, labor-intensive inputs: expert-written grading rubrics, bespoke reinforcement-learning environments, and annotated workflows reflecting real professional practice. Training a model to solve math problems or write syntactically valid code is relatively straightforward; training it to function reliably as a lawyer, consultant, doctor, or engineer is not.

This explains why AI development increasingly resembles industrial knowledge extraction. Thousands of domain experts—lawyers, physicists, consultants, medical professionals—are paid to externalize their tacit knowledge into checklists, workflows, and evaluative criteria that models can optimize against. As the article describes, these rubrics can take ten hours or more to produce and may include dozens of criteria per task, multiplied across tens or hundreds of thousands of task variants.

Crucially, this reality cuts against the AGI narrative. If intelligence truly generalized, the need for bespoke human data would decline over time. Instead, spending on human data is accelerating. AI systems improve not by abstract generalization, but by ever-narrower specialization, requiring continuous infusions of fresh, context-specific human input. As one researcher cited in the article argues, human data may become the primary bottleneck to future AI progress rather than a temporary scaffolding.

The result is a paradoxical economy. AI labs proclaim visions of autonomy and self-improvement while quietly constructing a global, high-skill human labor market to sustain incremental gains. This labor market is lucrative for intermediaries but unstable, legally contested, and structurally fragile—highly concentrated on a handful of buyers, vulnerable to shifts in training techniques, and already showing signs of commodification and churn.

Ultimately, the article suggests that AI may be less a march toward digital superintelligence and more a new form of infrastructure—powerful, transformative, but dependent on continuous human participation. In that world, the real winners are not those who promise intelligence without labor, but those who know how to organize, extract, and resell human expertise at scale.

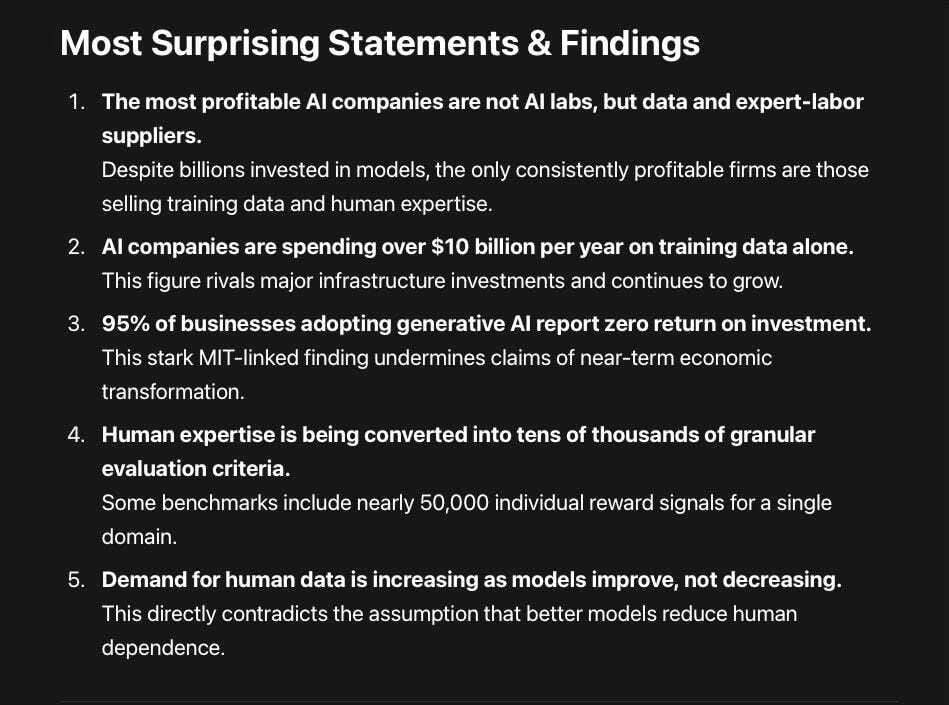

Most Surprising Statements & Findings

The most profitable AI companies are not AI labs, but data and expert-labor suppliers.

Despite billions invested in models, the only consistently profitable firms are those selling training data and human expertise.AI companies are spending over $10 billion per year on training data alone.

This figure rivals major infrastructure investments and continues to grow.95% of businesses adopting generative AI report zero return on investment.

This stark MIT-linked finding undermines claims of near-term economic transformation.Human expertise is being converted into tens of thousands of granular evaluation criteria.

Some benchmarks include nearly 50,000 individual reward signals for a single domain.Demand for human data is increasing as models improve, not decreasing.

This directly contradicts the assumption that better models reduce human dependence.

Most Controversial Statements & Findings

AGI narratives obscure the true cost structure of AI development.

Companies emphasize compute and scale while downplaying ballooning human-data costs.Reinforcement learning struggles with real-world ambiguity and conflicting values.

AI systems perform best where success is binary and verifiable—conditions rarely met in professional work.Much of AI “reasoning” is domain-bound rather than genuinely general.

Models excel in coding and math partly because these domains are unusually easy to verify.The data industry faces legal and ethical instability.

Many leading firms are already embroiled in wage-theft and misclassification lawsuits.AI progress increasingly resembles outsourcing rather than automation.

Human labor is not disappearing—it is being reorganized and abstracted behind interfaces.

Most Valuable Statements & Findings

Human data is now the core strategic asset in AI development.

Whoever controls expert labor and high-quality evaluation pipelines controls progress.AI is evolving into a customization economy, not a plug-and-play one.

Enterprises increasingly need bespoke models trained on domain-specific data.AI may follow the trajectory of “normal” technologies rather than god-like intelligence.

Like steam engines or the internet, AI could be transformative yet bounded and labor-dependent.Training data suppliers are the ‘picks and shovels’ of the AI gold rush.

Their business models are safer than frontier model building, though still volatile.The entire economy may increasingly function as a reinforcement-learning environment.

Workflows, decisions, and evaluations are being formalized so machines can learn from them.

Closing Reflection

The article’s deepest insight is not about which companies are winning today, but what AI fundamentally is becoming: not an autonomous intelligence replacing human judgment, but a vast socio-technical system that depends on the systematic extraction, codification, and resale of human expertise. That reality has profound implications for labor, knowledge industries, governance, and any sector—like publishing—that sits upstream of trusted human judgment rather than downstream of automation.