- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- The absence of senior technologists within the government’s strategic apex creates a profound “negotiation gap.” This gap prevents regulators from properly unbundling and valuing the propositions...

The absence of senior technologists within the government’s strategic apex creates a profound “negotiation gap.” This gap prevents regulators from properly unbundling and valuing the propositions...

...presented by Big Tech. Because leadership lacks the technical depth to challenge the underlying assumptions of these propositions, the state frequently defaults to a position of “dependency.”

Technocratic Imbalance in Global AI Governance: A Critical Analysis of Leadership Backgrounds, Cognitive Capture, and the Proactive Policy Deficit

by Gemini 3.0, Deep Research. Warning! LLMs may hallucinate!

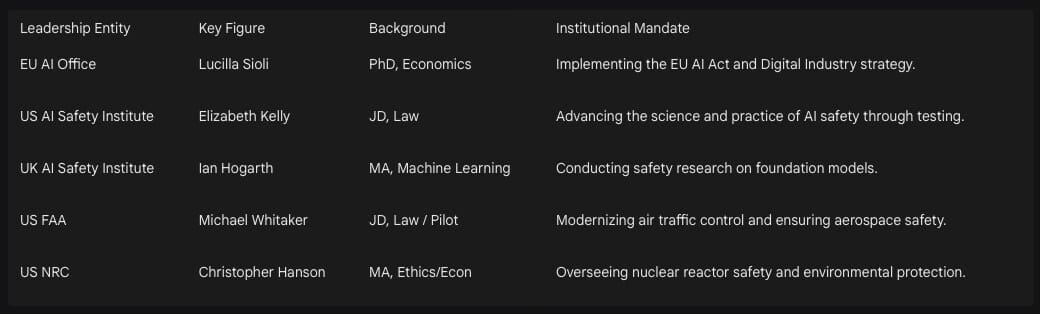

The Structural Divergence of Leadership in Global AI Policy

The current trajectory of artificial intelligence (AI) governance is increasingly defined by a profound structural paradox. While AI systems represent the most technically complex and rapidly evolving technologies in human history, the strategic leadership responsible for their oversight remains dominated by traditional administrative and legal profiles. An exhaustive review of the leadership structures in the European Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom reveals a persistent reluctance to elevate technologists to the highest levels of strategic decision-making. This deficit is not merely a matter of professional diversity; it represents a fundamental misalignment between the technical nature of the object of regulation and the cognitive frameworks of the regulators.

In the European Union, the implementation of the landmark AI Act is spearheaded by the Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology (DG CONNECT). The leadership of this body, exemplified by Director Lucilla Sioli, follows a classic civil service trajectory.1 Sioli’s academic background is in economics, holding doctoral degrees from the University of Southampton and the Catholic University of Milan.3 Having served as a career civil servant within the European Commission since 1997, her expertise is centered on market dynamics, the “Digital Single Market” strategy, and industrial policy.2 While this background provides a sophisticated understanding of how to harmonize regulations across member states, it lacks the firsthand technical experience in machine learning or software architecture required to anticipate the emergent behaviors of large-scale models. The reliance on economic and administrative metrics naturally prioritizes market competition and consumer protection over the more subtle technical vulnerabilities that define AI risk.

Conversely, the United States has established the AI Safety Institute (AISI) within the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The selection of Elizabeth Kelly as the inaugural director further reinforces the legalistic and policy-centric model of technology governance.5 Kelly is a lawyer by training, with a Juris Doctor from Yale and experience in the National Economic Council.7 Her primary contribution to the field has been her role as a lead drafter of President Biden’s Executive Order on AI, an achievement that highlights her prowess in navigating the complex machinery of federal regulation.7 However, as AI systems transition from “predictable” algorithms to “autonomous” agents, the limitations of a legal-first approach become apparent. Law is reactive and relies on precedents, whereas AI safety is a forward-looking engineering challenge.9

The United Kingdom stands out as a significant outlier by appointing Ian Hogarth, a machine learning specialist and tech entrepreneur, to chair its AI Safety Institute.10 Hogarth’s education in information engineering at Cambridge and his experience in the startup ecosystem provide a “builder’s” perspective that is largely absent in Brussels or Washington.10 The UK’s decision to model its taskforce on the success of the Vaccine Taskforce—emphasizing agility, private-sector expertise, and delegated authority—indicates an awareness that traditional bureaucratic structures are ill-equipped for high-velocity technological change.16 Nevertheless, this model faces its own challenges, particularly regarding the entanglement of public service with private financial interests, as evidenced by the rigorous divestment and recusal requirements imposed on Hogarth to manage conflicts of interest.17

The Negotiation Gap: Valuing Big Tech Propositions and Cognitive Capture

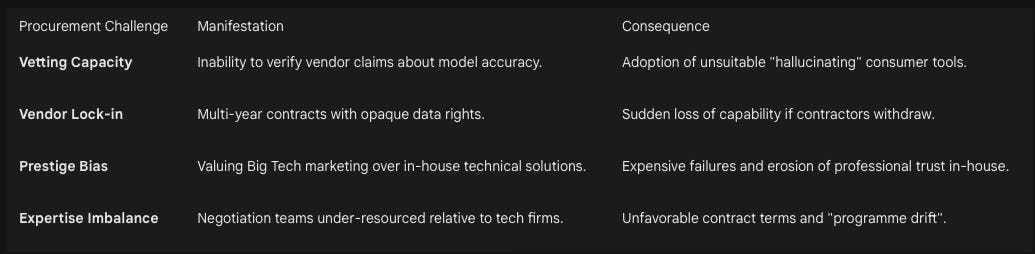

The absence of senior technologists within the government’s strategic apex creates a profound “negotiation gap.” This gap prevents regulators from properly unbundling and valuing the propositions presented by Big Tech corporations. When governments interact with firms like OpenAI, Google, or Microsoft, they are often met with a “technological monopoly” that is leveraged to reshape the policy landscape in favor of industry self-interest.18 Because leadership lacks the technical depth to challenge the underlying assumptions of these propositions, the state frequently defaults to a position of “dependency.”

This dependency is clearly visible in the realm of public procurement. Government agencies are increasingly rushing to adopt generative AI and data analytics tools without the in-house capacity to vet vendor claims or manage integration.19 The research highlights a consistent failure to differentiate between “value-driven AI” and marketing-driven “hype”.20 For instance, many agencies purchase off-the-shelf consumer-grade tools that are prone to “hallucinations” and lack the verification mechanisms required for public accountability.21 A leader without technical training may see a polished interface and conclude that the system is reliable, whereas a technologist would recognize that a statistical text generator is fundamentally different from an evidence-based advisor.21

A critical case study of this expertise imbalance is the United Kingdom’s contract with Palantir for the NHS Federated Data Platform (FDP). The £330 million deal was intended to solve operational data silos across the healthcare system.22 However, internal data professionals within the NHS have described the platform as a “backward step” and a “laughing stock,” noting that existing, publicly funded open-source tools often exceeded the capabilities of the Palantir solution.23 The failure of leadership to value internal expertise over the “prestige” of a global tech firm suggests a cognitive capture where administrative leaders are swayed by the discursive power of Big Tech.18 The lack of technical due diligence meant that the government failed to anticipate the “programme drift” and low adoption rates, with only 15% of NHS trusts actively using the system months after its award.24

The structural shift in power has reached a point where sovereign states are now treating Big Tech companies as “sovereign actors” or “net states”.18 Some governments have even assigned “tech ambassadors” to Silicon Valley, effectively acknowledging that these corporations exert more influence over digital infrastructure than the states themselves.18 Without technologists at the top who can evaluate these firms as competitors or collaborators on an architectural level, governments risk becoming “quasi-client states” that rely on private infrastructure for essential functions such as cybersecurity, virus tracking, and tax administration.18

Susceptibility to Marketing Hype and the Symbolic Governance Trap

The lack of technical expertise at the strategic level makes governments uniquely susceptible to believing marketing hype and succumbing to sophisticated lobbying. Big Tech firms have become “super policy entrepreneurs,” utilizing breakthroughs in generative AI (GenAI) as “focusing events” to shift the national mood back in their favor after years of “techlash”.18 This susceptibility often leads to “symbolic governance”—policies that look innovative on the surface but lack the technical rigor required to protect the public interest.

The research indicates that politicians frequently mistake consumer-grade AI for strategic policy advisors. Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson’s use of ChatGPT for “second opinions” on policy decisions is a prime example of this.21 While such a move may appear modern and forward-thinking, it ignores the technical reality that generic large language models (LLMs) are optimized for “plausibility” rather than “factual accuracy”.21 These systems lack the verification mechanisms and citation requirements essential for democratic accountability.21 When leaders fail to distinguish between a “statistical likelihood” of a text string and an “evidence-based” policy recommendation, they inadvertently outsource democratic judgment to opaque private algorithms.21

Lobbying also manifests in the subtle shifting of institutional mandates. In the United States, the evolution of the NIST AI Safety Institute Consortium (AISIC) working groups provides a stark example of how industry pressure can marginalize social concerns. Initially, a group titled “Society and Technology” was proposed to address the impact of AI on marginalized communities, focusing on bias and discrimination.28 However, as the institute’s structure was finalized, this group was replaced by a “Safety & Security” group.28 This transition reflected a move from “responsible AI”—which centers grounded human risk—to a more technical, national security-oriented “AI safety” narrative favored by frontier model labs.28 This shift makes it difficult for civil society to advance goals related to algorithmic harms, as the focus is diverted toward speculative “existential risks” rather than the immediate sociotechnical failures of the technology.28

This “discursive power” allows Big Tech to define the parameters of the debate. Because the AI research community is relatively culturally homogenous—predominantly Western, male, and English-speaking—the “evidence” provided for policy-making is inherently biased toward the values of that ingroup.32 Impacts that are “easy-to-measure,” such as compute thresholds, are prioritized over “hard-to-measure” impacts like the erosion of civic participation or the degradation of information integrity.32 Without senior leaders who can deconstruct these biases and understand the “culture and values” embedded in the research community, governments are essentially regulating based on a map drawn by the industry itself.32

Technical Exceptionalism: Why AI Requires Practitioner-Level Expertise

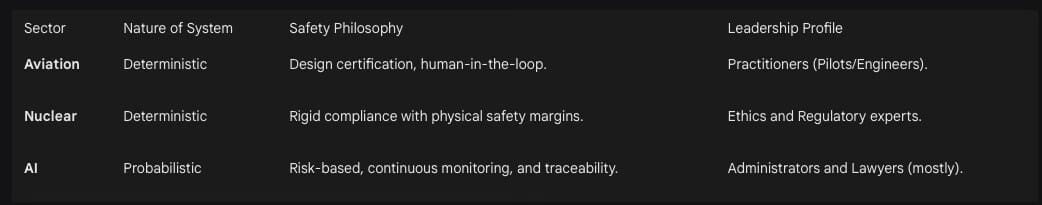

A core theme in the research is whether technologies like AI are genuinely different from other sectors in their requirement for technical expertise during the assessment of societal impacts. The evidence suggests that AI is indeed exceptional, primarily due to its “adaptivity” and “autonomy”.9 Unlike traditional safety-critical industries—such as aviation or nuclear power—where systems are deterministic and follow established physical laws, AI systems are probabilistic and achieve performance through “learning” rather than “design”.33

In the aviation industry, overseen by figures like FAA Administrator Michael Whitaker (who is himself a pilot), safety is ensured through the certification of specific designs and deterministic protocols.12 Every aspect of a traditional aircraft system can be explained by engineering principles.33 Similarly, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) can rely on “Regulatory Guides” that specify manual actions and computations because the physics of fission is well-understood.34

AI, however, breaks these traditional models of assurance. The “black box” nature of neural networks means that even the developers cannot fully explain the intent or logic behind specific outcomes.9 As AI systems are “trained” rather than programmed, they develop the ability to perform inferences not envisioned by their creators.9 This necessitates a shift from “substantive regulation” (banning specific designs) to “process regulation” (requiring transparent training documentation and continuous monitoring).32 A leader without a deep technical understanding of machine learning may fail to grasp that “validating” an AI system is not a one-time event, but a continuous process that must account for model “decay” and adversarial manipulation.25

Furthermore, the societal impacts of AI are “sociotechnical” in nature, meaning they cannot be understood in isolation from the cultural and economic conditions in which they operate.28 For example, the use of AI in “high-risk” sectors like recruitment or criminal justice can significantly impact social equity.36 Traditional administrative leaders may view “bias” as a technical glitch to be fixed with a better algorithm, whereas a technologist with sociotechnical training would recognize it as a fundamental limitation of the training data.31 The ability to interpret and critically evaluate AI outputs—knowing when to rely on the machine versus human judgment—is a competency that is currently severely lacking at the top levels of government.38

The “temporal dissonance” between the structural slowness of government and the rapid shifts in technology also reinforces the need for practitioner leadership. In the five years between 2020 and 2025, tools like Zoom and ChatGPT went from being unknown to being ubiquitous, fundamentally altering the fabric of society.39 Traditional administrative leaders, accustomed to the slow pace of legislative cycles, struggle to stay current with the latest “challenges and opportunities”.40 In contrast, a technologist-leader is more likely to prioritize “agility and adaptability” in adoption and recognize when emerging capabilities like “agentic AI” require an immediate shift in strategy.19

Talent Dynamics and the Institutional Erosion of the Public Sector

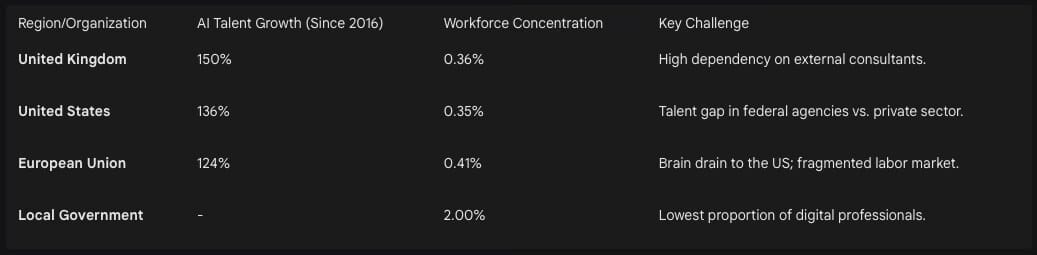

The proactive formulation of AI policy is also hindered by the global competition for AI talent and the resulting institutional erosion of the public sector. While Europe boasts a high concentration of AI professionals—30% higher per-capita than the US—it suffers from a chronic “brain drain” to the United States.42 The US tech sector’s massive financial resources, supercomputing infrastructure, and streamlined immigration paths act as a “magnet” for the world’s top AI minds.42

Within the public sector, this talent gap is even more acute. Compensation and career paths in government are uncompetitive with the private sector, especially for senior technical roles.43 This leads to a situation where only 2% of digital professionals work in local government, creating a high dependency on an increasingly concentrated market of suppliers.43 The UK public sector, for instance, spends 55% of its digital budget (£14.5 billion) on third-party contractors and consultants.43 These contractors cost three times as much as permanent civil servants and, more critically, they take their “institutional knowledge” with them when the contract ends.43

This erosion of talent creates a “feedback loop of incompetence.” As the public sector loses its technical “muscularity,” it becomes less capable of driving supplier performance or conducting meaningful oversight.43 Only 28% of government survey respondents believe their organizations can effectively manage supplier performance.43 This lack of internal expertise also feeds into “risk aversion,” as leaders who do not understand the technology are more likely to either block innovation entirely or embrace it uncritically.27

Furthermore, the geography of AI talent migration is shaped more by education systems and specific policies than by general immigration trends.42 For example, 45% of Germany’s AI workforce studied abroad, and Ireland attracts many AI professionals from India due to language and educational ties.42 Governments that do not put technologists in strategic positions are less likely to understand these “education-to-labor” pipelines and fail to create the “thriving tech environments” required to attract and retain the talent they need to govern.42

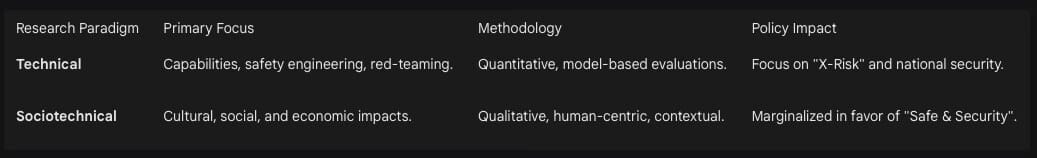

The Sociotechnical Divide: Marginalization of Immediate Harms

The research highlights a significant “sociotechnical divide” that is exacerbated by the lack of practitioner leadership. AI development and regulation are currently bifurcated between “technical research” (focused on internal mechanics) and “sociotechnical research” (focused on human risk).28 This divide is not merely academic; it has real-world consequences for how AI is governed.

When administrative leaders dominate AI policy, they often default to a “national security” or “economic competition” narrative.28 This is evident in the shift of U.S. policy under the Biden administration’s 2023 Executive Order, which signaled that AI was a matter of civil rights but also emphasized maintaining a “competitive edge”.46 This “pro-innovation” approach often prioritizes technological growth over “precautionary oversight,” aiming to ensure that the United States remains the commanding force in global standards.46

In this environment, “ethics” is often treated as a peripheral concern. UNESCO’s policy guidance on AI in education foregrounds ethical challenges like the digital divide and algorithmic bias, yet the underlying assumptions often drive “neoliberal, techno-solutionist” recommendations.29 These policies frequently represent education as a “site of value extraction” for tech markets rather than a public good to be protected from algorithmic surveillance.29 Without technologists who are also trained in the “humanities and social sciences,” policy-makers struggle to bridge the gap between “technical safety” (ensuring the code works) and “sociotechnical safety” (ensuring the system doesn’t harm society).28

The marginalization of sociotechnical concerns is further evidenced by the “existential risk” narrative. This narrative, which focuses on fictional superintelligent AI seizing control of capital or infrastructure, is often used to distract from immediate, grounded harms.28 For instance, the discussion around “misaligned goals” in superintelligence often overshadows the reality of “misaligned algorithms” that are currently causing racial bias in predictive policing or credit scoring.28 Because governments lack the technical depth to deconstruct these narratives, they are prone to being captured by the “speculative future” stories that favor the very companies they are supposed to regulate.28

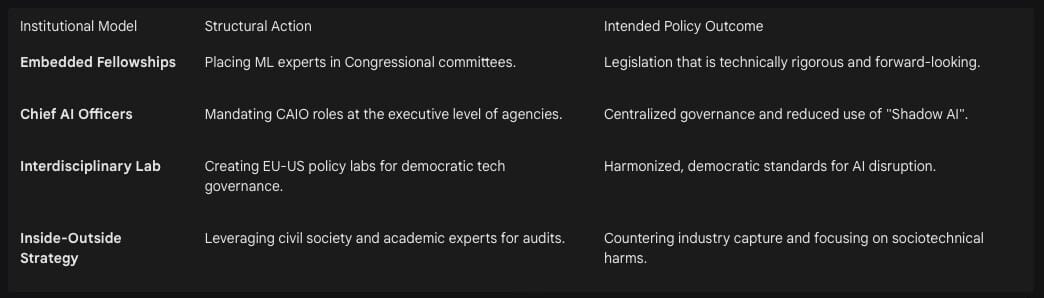

Recommendations for Addressing the Technocratic Deficit

To ensure proper checks and balances in the age of AI, governments and regulators must move beyond the current administrative-heavy model and adopt a more “practitioner-integrated” approach. This requires fundamental structural reforms in how technologists are recruited, embedded, and empowered within the machinery of the state.

Embedding Technologists in Legislative and Strategic Roles

The most critical reform is the permanent placement of technologists in leadership and advisory positions. The “Congressional Innovation Fellowship” model, which places engineers and computer scientists directly into legislative offices, should be expanded and formalized across all levels of government.47 These fellows provide the “informed, multidisciplinary support” needed to write and implement effective technology laws.48 By pairing technical expertise with hands-on legislative experience, the state can build an enduring pipeline of “civic technologists” who can sustain its ability to meet technological challenges.48

Overhauling Public Procurement for Technical Accountability

Governments must overhaul their procurement practices to bridge the “valuation gap.” This involves moving away from buying “off-the-shelf” tools without vetting, and toward “agile, outcome-based contracting”.19 Public agencies should utilize “internal sandboxes” to test and verify vendor claims before full-scale deployment.19 Furthermore, procurement officials should be encouraged to collaborate early with technical teams to ensure that they are not buying “expensive tools that don’t work” or that undermine public confidence.19

Specific contract clauses should be mandated to protect “data sovereignty” and ensure “continuity of operations”.25 This includes clarifying data ownership and rights, ensuring that the government can modify or control essential AI system components if a vendor withdraws.25 To build this capacity, the public sector must also prioritize the recruitment of permanent technical staff, aiming for the “high-performing” private sector ratio of four technical staff to every one project manager.43

Establishing a “Public AI” Infrastructure

To counter the “monopoly” of Big Tech, democratic societies should invest in “public AI” frameworks.21 These are systems built or governed by public-private consortia explicitly for public benefit, with democratic oversight.21 Examples include purpose-built platforms for policy consultation—like the UK’s AI Consultation Analyzer—which amplify democratic participation rather than replacing it.21 This public infrastructure would ensure that the “rules” of AI deployment are not set in secret by private platforms but reflect the diverse needs of the communities they serve.21

Such a framework would also include:

Mandatory Audits: Requiring rigorous testing and validation of AI systems used in high-stakes public decisions.21

Plain-Language Documentation: Ensuring that citizens can understand the logic behind AI-driven decisions that affect them.19

Participatory Governance: Involving affected communities and civil society in the design and evaluation of AI tools to mitigate bias and ensure fairness.37

Creating an Autonomous AI Regulatory Authority (AIRA)

Finally, there is a growing case for the establishment of a dedicated “AI Regulatory Authority” (AIRA).53 Such an authority would be responsible for implementing technical safety standards for the most powerful AI systems.53 It would evaluate evidence from training procedures, interpretability techniques, and red-teaming efforts to ensure that societal-scale risks are kept below an acceptable threshold.53 By creating an institution that is “technically muscular” and capable of responding flexibly to new developments, governments can finally transition from a reactive, hype-driven stance to a proactive, evidence-based strategy.32

Conclusion: Rebalancing the Technocratic Equation

The research demonstrates that the current difficulties faced by governments and regulators in formulating solid AI policy are fundamentally rooted in a “belief gap”—the mistaken belief that technology is merely a “tool” to be managed by administrative generalists rather than an “environment” that requires practitioner-level navigation. The exclusion of technologists from strategic decision-making has led to a “cognitive capture” where the state is unable to properly value Big Tech propositions, prone to marketing hype, and blind to the unique technical nature of AI risk.

To address this, the state must reclaim its technical “muscularity.” This involves not just hiring more coders, but elevating those with deep technical knowledge to positions of strategic power where they can shape the “architectural” decisions of the digital age. By embedding technologists in leadership, overhauling procurement, and fostering a public-interest AI infrastructure, democratic societies can ensure that technology serves their values, rather than subverting them through negligence or naivety. The goal is a balanced ecosystem where human judgment—informed by technical reality—always guides the final decision.

Works cited

Lucilla Sioli - OECD Events, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.oecd-events.org/e/ai-wips-2023/speaker/a783a9e2-49c0-ed11-9f73-6045bd8890e4/lucilla-sioli

Meet Lucilla Sioli at ISES!, accessed January 29, 2026, https://theisig.com/profiles/lucilla-sioli/

Lucilla Sioli - CERRE, accessed January 29, 2026, https://cerre.eu/biographies/lucilla-sioli/

Lucilla Sioli — AI Summer School - KU Leuven, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.law.kuleuven.be/ai-summer-school/documentation/biographies/lucilla-sioli

Elizabeth Kelly | AI Policy Leader at US Safety Institute - Dr. Ayesha Khanna, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.ayeshakhanna.com/women-in-ai-feature/elizabeth-kelly

VIDEO: Elizabeth Kelly on risk, innovation and the future of work - Harvard Business School, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.hbs.edu/bigs/elizabeth-kelly-artificial-intelligence-future-of-work

Elizabeth Kelly: The 100 Most Influential People in AI 2024 | TIME, accessed January 29, 2026, https://time.com/collections/time100-ai-2024/7012783/elizabeth-kelly/

FIRSTS Conversation with the First Director of the US Artificial Intelligence Safety Institute, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.fcc.gov/news-events/podcast/firsts-conversation-first-director-us-artificial-intelligence-safety-institute

A Comparative Perspective on AI Regulation | Lawfare, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/a-comparative-perspective-on-ai-regulation

Ian Hogarth - Wikipedia, accessed January 29, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ian_Hogarth

About | The AI Security Institute (AISI), accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.aisi.gov.uk/about

Michael Whitaker, FAA Administrator - Congress.gov, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.congress.gov/118/meeting/house/116719/witnesses/HHRG-118-PW05-Bio-WhitakerM-20240206.pdf

Michael G. Whitaker, accessed January 29, 2026, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/GO/GO00/20150617/103635/HHRG-114-GO00-Bio-WhitakerM-20150617.pdf

Christopher T. Hanson - Nuclear Regulatory Commission, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML2214/ML22145A383.pdf

Christopher Hanson - Capstone DC, accessed January 29, 2026, https://capstonedc.com/team-member/christopher-hanson/

Tech entrepreneur Ian Hogarth to lead UK’s AI Foundation Model Taskforce - GOV.UK, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/tech-entrepreneur-ian-hogarth-to-lead-uks-ai-foundation-model-taskforce

Ian Hogarth’s declared outside interests - GOV.UK, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ian-hogarths-declared-outside-interests/ian-hogarths-declared-outside-interests

Why and how is the power of Big Tech increasing in the policy ..., accessed January 29, 2026, https://academic.oup.com/policyandsociety/article/44/1/52/7636223

Governments risk “expensive failures” without smarter AI ..., accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.open-contracting.org/news/governments-risk-expensive-failures-without-smarter-ai-procurement-new-report/

AI hype, economic reality, and the future of work - techUK, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.techuk.org/resource/ai-hype-economic-reality-and-the-future-of-work.html

When Politicians Mistake AI Hype for Strategy | TechPolicy.Press, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.techpolicy.press/when-politicians-mistake-ai-hype-for-strategy/

Palantir used by the United Kingdom National Health Service?! : r/dataengineering - Reddit, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/dataengineering/comments/1nsji5v/palantir_used_by_the_united_kingdom_national/

We’d like to use additional cookies to understand how you use the site and improve our services. - UK Parliament Committees, accessed January 29, 2026, https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/144050/html/

No Palantir in the NHS and Corporate Watch Reveal the Real Story Behind the Federated Data Platform Rollout, accessed January 29, 2026, https://corporatewatch.org/foi-requests-reveal-palantirs-nhs-fdp-rollout-failures/

AI Won’t Outrun Bad Procurement - RAND, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2025/09/ai-wont-outrun-bad-procurement.html

Challenges in AI Public Procurement - MIAI - AI-Regulation.com, accessed January 29, 2026, https://ai-regulation.com/ai-public-procurement-challenges/

Implementation challenges that hinder the strategic use of AI in government - OECD, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/governing-with-artificial-intelligence_795de142-en/full-report/implementation-challenges-that-hinder-the-strategic-use-of-ai-in-government_05cfe2bb.html

Troubling translation: Sociotechnical research in AI policy and ..., accessed January 29, 2026, https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/troubling-translation-ai-policy-and-governance

Full article: The ethics of AI or techno-solutionism? UNESCO’s policy guidance on AI in education - Taylor & Francis, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01425692.2025.2502808

From nuclear stability to AI safety: Why nuclear policy experts must help shape AI’s future | European Leadership Network, accessed January 29, 2026, https://europeanleadershipnetwork.org/commentary/from-nuclear-stability-to-ai-safety-why-nuclear-policy-experts-must-help-shape-ais-future/

The ethics of AI decision-making: Balancing innovation and accountability - International Journal of Science and Research Archive, accessed January 29, 2026, https://ijsra.net/sites/default/files/IJSRA-2024-1548.pdf

Pitfalls of Evidence-Based AI Policy - arXiv, accessed January 29, 2026, https://arxiv.org/html/2502.09618v3

FAA Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence Safety Assurance, Version I, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.faa.gov/aircraft/air_cert/step/roadmap_for_AI_safety_assurance

Regulatory Framework Gap Assessment for the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Nuclear Applications, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML2429/ML24290A059.pdf

A Cross-Regional Review of AI Safety Regulations in the Commercial Aviation Industry, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3387/16/1/53

AI Governance: Overcoming Policy Barriers to Fairness and Privacy - Digital Commons @ UConn - University of Connecticut, accessed January 29, 2026, https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1642&context=law_review

AI Governance Series | Institute for Technology Law & Policy, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.law.georgetown.edu/tech-institute/initiatives/ai-governance-series/

Artificial Intelligence in Aviation: New Professionals for New Technologies - MDPI, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/13/21/11660

Blog - TechCongress, accessed January 29, 2026, https://techcongress.io/blog

Join the Congressional Innovation Fellowship - TechCongress, accessed January 29, 2026, https://techcongress.io/congressional-innovation-fellowship

AI’s Reality Check: From Hype to Hard Decisions on Skills, Ethics, and Infrastructure, accessed January 29, 2026, https://helium42.com/blog/ai-reality-check-skills-ethics-infrastructure

Europe’s AI Workforce: Mapping the Talent Behind the Code, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.eitdeeptechtalent.eu/news-and-events/news-archive/europes-ai-workforce-mapping-the-talent-behind-the-code/

State of digital government review - GOV.UK, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/state-of-digital-government-review/state-of-digital-government-review

AI in the EU: - 2024 Trends and Insights from LinkedIn, accessed January 29, 2026, https://economicgraph.linkedin.com/content/dam/me/economicgraph/en-us/PDF/AI-in-the-EU-Report.pdf

3 Challenges to Overcome for AI/ML Adoption in the Federal Government, accessed January 29, 2026, https://fedtechmagazine.com/article/2025/07/3-challenges-overcome-aiml-adoption-federal-government

AI Governance at a Crossroads: America’s AI Action Plan and its Impact on Businesses, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.ethics.harvard.edu/news/2025/11/ai-governance-crossroads-americas-ai-action-plan-and-its-impact-businesses

Join the Congressional Innovation Fellowship - TechCongress, accessed January 29, 2026, https://techcongress.io/congressional-innovation-fellowship-1

From Fellows to Staffers: 2025 Congressional Innovation Fellows - TechCongress, accessed January 29, 2026, https://techcongress.io/blog/2025/12/5/from-fellows-to-staffers-2025-congressional-innovation-fellows

Most UK and EU C-Suite leaders see chief AI officer role becoming key, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.staffingindustry.com/news/global-daily-news/most-uk-and-eu-c-suite-leaders-see-chief-ai-officer-role-becoming-key

Wolters Kluwer survey finds broad presence of unsanctioned AI tools in hospitals and health systems, accessed January 29, 2026, https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/news/wolters-kluwer-survey-finds-broad-presence-of-unsanctioned-ai-tools-in-hospitals-and-health-systems

Offering AI Expertise to Policymakers on Both Sides of the Atlantic | Stanford HAI, accessed January 29, 2026, https://hai.stanford.edu/news/offering-ai-expertise-policymakers-both-sides-atlantic

Understanding the Artificial Intelligence Revolution and its Ethical Implications - PMC, accessed January 29, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12575553/

A REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR ADVANCED ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE - Regulations.gov, accessed January 29, 2026, https://downloads.regulations.gov/NTIA-2023-0005-1416/attachment_2.pdf