- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Ted Entertainment v. Snap: YouTube is designed to let the public stream videos, not obtain the underlying files, and Snap allegedly engineered a pipeline to defeat that architecture at scale...

Ted Entertainment v. Snap: YouTube is designed to let the public stream videos, not obtain the underlying files, and Snap allegedly engineered a pipeline to defeat that architecture at scale...

...for commercial AI training. It becomes a case about breaking an access-control system—and doing so millions of times.

“The Copy You Were Never Supposed to Get”: Why Ted Entertainment v. Snap Is a DMCA Anti-Circumvention Test Case for the AI Video Era

by ChatGPT-5.2

The complaint in Ted Entertainment, Inc. et al. v. Snap Inc. is notable less for what it alleges—large-scale AI training on online video—and more for how it chooses to litigate it. Rather than leading with traditional copyright infringement theories (reproduction, derivative works, etc.), plaintiffs frame this as a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) §1201 anti-circumvention case built around a simple proposition: YouTube is designed to let the public stream videos, not obtain the underlying files, and Snap allegedly engineered a pipeline to defeat that architecture at scale for commercial AI training.

That choice is strategic. If plaintiffs can persuade a court that YouTube’s streaming-only delivery and related protections qualify as “effective technological measures,” then the legal fight shifts away from messy debates about fair use, transformation, or whether model training is “copying” in the conventional sense. It becomes a case about breaking an access-control system—and doing so millions of times.

What the plaintiffs are actually accusing Snap of doing

The complaint alleges Snap wanted training data for a “text-to-video” (and related) generative AI system and treated YouTube as a vast, high-quality reservoir of audiovisual works.

The alleged workflow is concrete:

Snap purportedly used large “index-style” datasets that list YouTube IDs, URLs, and timestamps—not the videos themselves—so using them requires separately retrieving the underlying audiovisual files from YouTube.

Plaintiffs identify HD-VILA-100M (compiled by Microsoft Research Asia and released for research) as a key upstream dataset and argue Snap used it as a springboard for its own dataset, Panda-70M, with tens of millions of clips and captions.

To do the actual downloading, plaintiffs allege Snap used tooling such as yt-dlp (a YouTube downloader) and operational tactics like virtual machines and IP rotation to avoid detection and blocking—i.e., the system was “intentionally designed” to defeat YouTube’s controls.

Plaintiffs emphasize the difference between “Premium offline viewing” (still controlled, time-limited, app-bound streaming) versus acquiring the real filesand storing them indefinitely inside Snap’s infrastructure.

The plaintiffs then define a nationwide class: U.S. creators whose videos (or material portions) appear in HD-VILA-100M and Panda-70M and were scraped/downloaded by Snap.

The most surprising, controversial, and valuable statements and findings

1) The case is almost entirely a DMCA §1201 play (and that’s the point)

The complaint’s center of gravity is the claim that YouTube’s Terms of Service plus its access controls constitute “effective technological measures” under §1201, and that every act of circumvention is its own violation.

Why this is surprising/valuable: It’s a deliberate attempt to route around fair-use defenses and instead litigate the “how did you get the file?” question—an approach that, if successful, could become a template for rightsholders confronting AI training pipelines built on scraping.

2) “Most YouTube videos are not registered”—and plaintiffs treat that as a feature, not a bug

The complaint explicitly notes that many YouTube works aren’t registered with the Copyright Office and argues that registration is not a prerequisite for §1201 anti-circumvention remedies.

Why it’s controversial: It implicitly invites creators to pursue leveragewithoutthe administrative burden of registration (though registration still matters for other claims). It’s also a reminder that §1201 can be wielded even where traditional infringement litigation is procedurally or economically difficult.

3) The “dataset is only pointers” argument: a crucial reframing of responsibility

Plaintiffs hammer the claim that these datasets don’t “contain” videos—only pointers—and therefore the entity using the dataset must do the downloading and circumvention itself.

Why it’s valuable: This is a direct attempt to close the rhetorical escape hatch: “We just used an academic dataset.” The complaint says, in effect:No—by definition you had to do the copying; the index doesn’t copy itself.

4) The “clip-by-clip” theory: multiplying violations at industrial scale

The complaint alleges that because datasets specify timestamps for clips, extraction may require repeated retrieval of the same source video and that each clip retrieval constitutes a distinct act of circumvention/copying, potentially yielding massive statutory exposure.

Why it’s controversial: Courts may resist a damages theory that scales exponentially with technical granularity, but plaintiffs are clearly trying to create settlement pressure by tying liability to the mechanics of modern training corpora.

5) Naming tools and tactics (yt-dlp, VMs, IP refresh) makes this pleading unusually “operational”

They don’t just allege “scraping.” They allege a specific anti-detection stack: downloader + virtual machines + IP rotation to defeat monitoring and blocks.

Why it’s valuable: This kind of specificity is exactly what survives early motions more often than broad “they scraped us” claims—and it tees up targeted discovery (logs, contractor instructions, procurement trails, cloud spend, IP rotation infrastructure, etc.).

6) “Once AI ingests content, it’s not capable of deletion or retraction” (a sweeping claim)

Plaintiffs state that creators will never be able to “claw back” the IP once it’s inside the model and characterize that irreversibility as part of the harm.

Why it’s controversial: Technically and legally, “deletion” is a spectrum (dataset deletion, checkpoint destruction, retraining, machine unlearning, etc.). Plaintiffs likely use this language to justify strong injunctive relief and to stress the existential asymmetry: scrape once, benefit forever.

7) The complaint leans on YouTube’s stance as an enforcement narrative amplifier

It quotes YouTube CEO Neal Mohan emphasizing creators’ expectations and the ToS prohibition on downloading “video bits.”

Why it matters: Plaintiffs are trying to align creator rights with platform governance: “YouTube tried to prevent this; Snap allegedly bypassed it anyway.” That alignment is rhetorically powerful—even if, legally, a platform’s ToS is not automatically a DMCA “technological measure.”

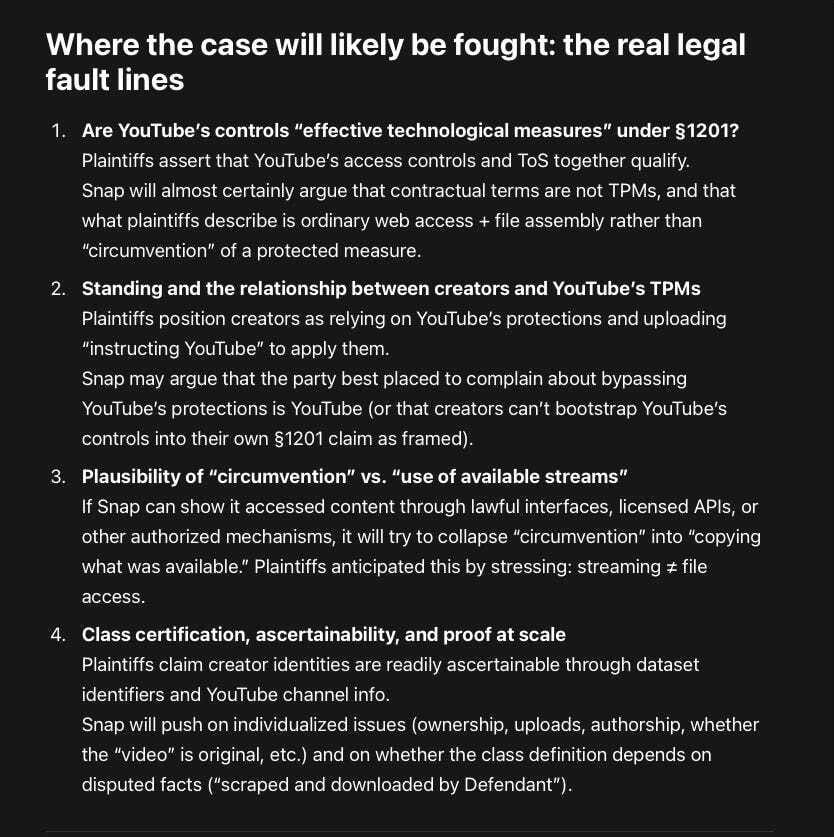

Where the case will likely be fought: the real legal fault lines

Are YouTube’s controls “effective technological measures” under §1201?

Plaintiffs assert that YouTube’s access controls and ToS together qualify.Snap will almost certainly argue that contractual terms are not TPMs, and that what plaintiffs describe is ordinary web access + file assembly rather than “circumvention” of a protected measure.

Standing and the relationship between creators and YouTube’s TPMs

Plaintiffs position creators as relying on YouTube’s protections and uploading “instructing YouTube” to apply them.Snap may argue that the party best placed to complain about bypassing YouTube’s protections is YouTube (or that creators can’t bootstrap YouTube’s controls into their own §1201 claim as framed).

Plausibility of “circumvention” vs. “use of available streams”

If Snap can show it accessed content through lawful interfaces, licensed APIs, or other authorized mechanisms, it will try to collapse “circumvention” into “copying what was available.” Plaintiffs anticipated this by stressing: streaming ≠ file access.Class certification, ascertainability, and proof at scale

Plaintiffs claim creator identities are readily ascertainable through dataset identifiers and YouTube channel info.Snap will push on individualized issues (ownership, uploads, authorship, whether the “video” is original, etc.) and on whether the class definition depends on disputed facts (“scraped and downloaded by Defendant”).

Predictions: how this case may conclude

Most likely path: partial survival at the motion-to-dismiss stage → settlement

Because the complaint is unusually detailed about datasets and alleged toolchains, there’s a credible chance it survives an early motion—at least enough to open discovery.

Discovery risk (logs, model training documentation, contractor emails, dataset provenance) is precisely the leverage plaintiffs want, and it’s where defendants often choose to settle.

A plausible mid-case outcome: the court narrows the §1201 theory

Even if plaintiffs get traction, a judge may:

narrow what counts as “circumvention,”

reject damages “per clip,” or

require a tighter showing that a specific technological measure was bypassed (not merely ToS breached).

A non-trivial alternative: dismissal if the TPM theory is viewed as overextended

If the court concludes YouTube’s system doesn’t meet §1201’s “effective technological measure” threshold as alleged, or that plaintiffs can’t premise §1201 liability on the combination of ToS + platform design, the case could be dismissed (or plaintiffs forced to replead with more specificity about the precise technical controls circumvented).

Net prediction

More likely than not: the case becomes a settlement-with-guardrails event (confidential payment + commitments about data sourcing), because the reputational and discovery exposure for an AI developer accused of evading platform controls can be more damaging than the merits fight. But the key precedent risk is real: if plaintiffs win a strong §1201 ruling, it could supercharge a wave of creator-led anti-circumvention suits that avoid fair-use trench warfare.

Recommendations based on the learnings in this case

For AI developers (and the product/legal teams that serve them)

Treat “streaming-only” platforms as access-controlled environments, not free reservoirs

If your pipeline requires reconstructing or extracting underlying files, assume you’re in §1201 danger territory—especially if you’re using downloader tooling and evasion tactics.Stop laundering provenance through “academic-only” datasets

If a dataset is “pointers + timestamps,” it is essentially a scraping instruction set. Plaintiffs explicitly attack “academic-only” licensing as incompatible with commercial training.Build governance that blocks research-only datasets from production training unless you have written licensing coverage.

Operational compliance matters: your tooling becomes your intent

This complaint shows how quickly a tool like yt-dlp + IP rotation becomes evidence of deliberate circumvention.Create internal red lines: no downloader stacks, no bot evasion, no rotating proxies for restricted sources.

Build auditable data supply chains (and assume you’ll have to prove them)

Maintain logs and documentation that show:

source authorization,

API terms compliance,

licensing scope,

dataset lineage, and

purge/retraining procedures if a dataset is later challenged.

The absence of records can be interpreted as willfulness when the alleged conduct is industrial scale.

Design for “reversibility”

Plaintiffs stress irreversibility (“not capable of deletion”).Even if you disagree technically, you should be able to demonstrate practical remediation: dataset removal, checkpoint retirement, re-training triggers, and documented mitigation.

For other litigants (creators, publishers, platforms, and collective actions)

Plead the pipeline, not the vibe

This complaint is strongest where it names datasets, explains pointer mechanics, and identifies toolchains (yt-dlp, VMs, IP rotation).If you’re suing, mirror that: make the court see the machinery.

Consider §1201 as a strategic complement, not a replacement

Even if you ultimately bring infringement claims, §1201 can shift early leverage because it targets access-bypass behavior. Plaintiffs explicitly frame the streaming/file distinction as “critical.”Use dataset identifiers for class design and notice

Plaintiffs argue ascertainability through URLs/IDs and YouTube channel mapping.That’s a practical playbook for mass-rightsholder cases: anchor membership in objective lists.

Anticipate the “ToS is not a TPM” counterattack

If your theory depends on platform terms, pair it with technical evidence: authentication gates, rate-limits, signature mechanisms, encrypted delivery, token checks—anything that looks like an access-control measure beyond contract language.Don’t overclaim technical absolutes

Statements like “content stored in a neural network is not capable of deletion” are rhetorically potent but contestable.A smarter long-game is to demand verifiable remediation standards rather than metaphysical claims about model memory.