- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Technologies appearing benign could possess dual-use capabilities, potentially enabling surveillance or even warfare against adopting nations in the future.

Technologies appearing benign could possess dual-use capabilities, potentially enabling surveillance or even warfare against adopting nations in the future.

This report examines the evidence supporting and countering this perspective, analyzing the mechanisms of US surveillance, the dual-use nature of modern technology, and the impacts on non-US entities.

by Google Gemini, Deep Research with 2.5 Pro. Warning, LLMs may hallucinate!

Chapter 1: The US Surveillance Architecture and its Global Reach

1.1 Introduction: The Double-Edged Sword of US Technology

The global economy and society are increasingly reliant on technologies originating from the United States, particularly from Silicon Valley. These innovations offer substantial benefits in efficiency, connectivity, and economic growth.1 However, this deep integration comes with inherent risks, particularly concerning surveillance capabilities embedded within the US legal and technological framework. Concerns have been raised that technologies appearing benign could possess dual-use capabilities, potentially enabling surveillance or even warfare against adopting nations in the future. This report examines the evidence supporting and countering this perspective, analyzing the mechanisms of US surveillance, the dual-use nature of modern technology, and the documented impacts on non-US entities. It concludes with strategic recommendations for non-US territories seeking to mitigate these risks and explores the potential consequences of inaction.

1.2 Key Legal Frameworks Enabling US Surveillance

The capacity of the US government to conduct surveillance, particularly involving data held by technology companies, rests on several key legal authorities. These frameworks grant intelligence and law enforcement agencies significant power to access communications and stored data, often with implications reaching far beyond US borders.

Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Section 702: Enacted as part of the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, Section 702 is a cornerstone of US foreign intelligence collection.3 It authorizes the targeting of non-US persons reasonably believed to be located outside the United States to acquire foreign intelligence information.4 This authority underpins major surveillance programs like PRISM, compelling US-based electronic communication service providers (CSPs) such as Google, Apple, Microsoft, Meta (Facebook), and others to turn over data matching court-approved selectors.3 Data collected can include emails, chats, photos, stored data, and voice-over-IP communications.3 Section 702 requests are approved in batches by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), a body that operates largely in secret, rather than requiring individual warrants based on probable cause for each target.6 While ostensibly targeting foreigners abroad, Section 702 inevitably captures communications involving US persons if they are communicating with a foreign target – the so-called "backdoor loophole" or "incidental collection".4 This collected data, including that of US persons, is stored in NSA databases searchable by agencies like the FBI, sometimes without a warrant specifically authorizing the search for that US person's information.6 Documents leaked by Edward Snowden indicated PRISM was the "number one source of raw intelligence used for NSA analytic reports," accounting for 91% of internet traffic acquired under Section 702.3 While companies named often deny providing "direct access" to their servers, they acknowledge complying with legally binding orders for specific accounts or identifiers.3 The FBI's Data Intercept Technology Unit (DITU) handles the actual data interception process, sending selectors to the service providers.3 Recent reauthorization of Section 702 has potentially expanded the definition of CSPs that can be compelled to assist, possibly including entities like landlords or businesses offering WiFi.7

Executive Order 12333: Signed by President Reagan and subsequently modified, EO 12333 provides broad authority for the US intelligence community (IC) to collect foreign intelligence from communications conducted exclusively outside the United States.9 This includes signals intelligence (SIGINT) gathered from satellites or international communication links that do not terminate in the US.4 Because the targets are non-US persons located abroad, surveillance under EO 12333 generally does not require a warrant under the Fourth Amendment.9 Critically, if communications of US persons are incidentally collected as part of foreign intelligence gathering under EO 12333 (e.g., communications routed through servers outside the US without a US endpoint), this data, including content, can be retained.4 This collection occurs outside the specific oversight mechanisms mandated for Section 702 collection within the US.4

The CLOUD Act (Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act): Enacted in 2018, the CLOUD Act explicitly grants US law enforcement the authority to compel US-based technology providers to disclose data within their possession, custody, or control, regardless of where that data is stored globally.11 This extraterritorial reach means a US warrant or other legal process served on a US company can require the production of data stored on servers in Europe, Asia, or elsewhere.11 The Act aims to streamline access to electronic evidence for law enforcement, bypassing potentially slower Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) processes.12 While it requires a warrant for communication content and allows companies to challenge requests that conflict with foreign law under certain conditions, its fundamental premise creates direct conflicts with data protection regimes like the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which seeks to limit third-country access to residents' data.11 The CLOUD Act also allows for bilateral executive agreements where foreign governments meeting certain human rights and privacy standards can request data directly from US providers, and vice-versa.11

These legal instruments operate in concert, leveraging the global footprint of US technology companies. The FISA court's secrecy and the frequent use of gag orders prevent companies from disclosing the nature and volume of requests, creating an opaque system where individuals, companies, and even foreign governments may be unaware their data is being accessed.7 This lack of transparency severely hinders accountability and the possibility of legal or diplomatic recourse. Furthermore, the US government also acquires vast amounts of data, including sensitive personal information, by purchasing it from commercial data brokers, bypassing warrant requirements altogether.10 The combination of these legal authorities and practices effectively transforms parts of the global digital infrastructure, dominated by US firms, into potential collection platforms for US intelligence and law enforcement, extending their reach far beyond US shores. The very structure of these laws appears designed to utilize the market dominance of US tech firms as a strategic asset for intelligence gathering.

1.3 The Enduring Impact of the Snowden Revelations

The global debate surrounding US surveillance practices was irrevocably altered in 2013 by the disclosures of former NSA contractor Edward Snowden.3 Leaking classified documents to journalists, Snowden exposed the existence and operational details of mass surveillance programs, most notably PRISM, and the vast scale of data collection undertaken by the NSA and its international partners, such as the UK's GCHQ.3 Snowden characterized some of these activities as "dangerous" and "criminal," warning that the extent of government surveillance capabilities far exceeded public knowledge.3

These revelations triggered international outrage and diplomatic friction, with allies like Germany describing the potential scope of interception as "nightmarish".3 The disclosures confirmed that major US technology companies were compelled to cooperate with NSA surveillance programs under FISA Section 702.3 They shattered assumptions about online privacy and significantly damaged trust between citizens, technology companies, and governments, particularly the US government.4 The Snowden leaks provided concrete evidence of the capabilities enabled by the legal frameworks discussed above, demonstrating how laws intended for foreign intelligence could result in the mass collection of communications, including those of ordinary citizens worldwide. The impact continues to resonate, fueling ongoing debates about privacy, security, government oversight, and the need for reform.4

The operational reality exposed by Snowden underscored the porous nature of the distinction between targeting "foreigners" and protecting "US persons." Given the global interconnectedness facilitated by US-based platforms, targeting foreign individuals under Section 702 inevitably sweeps up the communications of countless US persons and citizens of other nations who interact with them.4 The subsequent ability to query these vast datasets for information on US persons using the "backdoor search" loophole, often without a specific warrant, further blurred this line.7 This operational reality means that surveillance authorizations aimed at specific foreign threats effectively create a much broader surveillance capability impacting individuals globally.

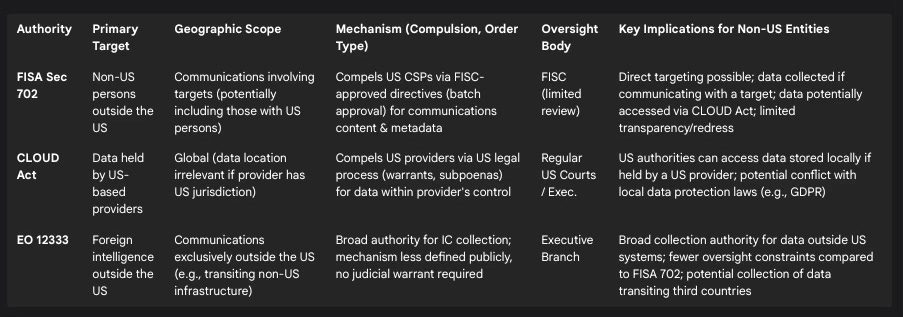

Table 1: Comparison of Key US Surveillance Authorities

Chapter 2: The Dual-Use Conundrum: Innovation's Shadow

2.1 Understanding Dual-Use Technologies

The term "dual-use" refers to technologies possessing both civilian/commercial and military/intelligence applications.16 While traditionally applied to items like specific chemicals or nuclear materials, the concept is increasingly relevant to the digital realm. Many innovations emerging from Silicon Valley and the broader tech industry, such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics, the Internet of Things (IoT), advanced semiconductor design, quantum computing, and even social media platforms, are inherently dual-use.16 Technologies developed for optimizing logistics, personalizing advertising, improving medical diagnostics, or connecting devices in smart homes can often be readily adapted for military reconnaissance, intelligence analysis, target identification, cyber warfare, or population surveillance.17 The rapid diffusion of these technologies, particularly software-based innovations like AI which are often open-source, makes controlling their spread and application exceptionally difficult.21 This dual-use nature means that advancements driven by commercial incentives can inadvertently, or sometimes intentionally, enhance state capabilities for surveillance and conflict.16

2.2 Evidence of Benign Technologies Repurposed for Surveillance and Conflict

The repurposing of commercially developed technologies for surveillance and military applications is not theoretical; it is an observable reality across several domains:

Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytics: AI algorithms designed for tasks like image recognition in consumer applications (e.g., tagging photos) can be trained to identify military targets or monitor specific activities in surveillance footage.18 Pattern analysis developed for market forecasting or fraud detection can be used for predictive policing or identifying potential dissidents.17 Advanced AI, particularly foundation models trained on vast datasets, is being explored and, in some cases, deployed for intelligence analysis, target acquisition, and reconnaissance.19 This includes the development of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS) that can independently identify and engage targets without real-time human control.17 However, the use of AI in these contexts carries significant risks. AI algorithms can inherit and amplify biases present in their training data, leading to disproportionate misidentification rates for certain demographic groups, such as racial minorities and women.25 Furthermore, large foundation models, often trained on publicly available and potentially personal data scraped from the internet, pose unique threats. They can generate false positives, leading to the targeting of innocent civilians, as pattern-matching capabilities may extrapolate connections that lack real-world validity.19 The reliance on web-scale datasets also makes these models vulnerable to "data poisoning" attacks, where adversaries intentionally introduce malicious data to manipulate the AI's behavior.19

Internet of Things (IoT) and Sensors: The proliferation of internet-connected devices in homes, cities (smart cities), and industrial settings creates an exponentially expanding network of sensors generating massive streams of data.26 While intended for efficiency, convenience, or monitoring infrastructure, this data can be intercepted or accessed by intelligence agencies, providing detailed insights into movements, activities, and environmental conditions for surveillance purposes.26 Even seemingly innocuous devices like connected thermostats or automobiles collect data that could be exploited.27

Communication Platforms: As established in Chapter 1, commercial communication platforms – including email services, video and voice chat applications (like Skype), and social media networks – are routinely leveraged by governments under legal compulsion (like FISA Section 702) to access user communications and data.3 Social media monitoring tools are also used by law enforcement, sometimes controversially, to track public posts and identify individuals, even those participating in protests.28 These platforms, designed for connection and information sharing, become critical conduits for state surveillance.

The commercial imperative to innovate in areas like AI and big data analytics, primarily centered in hubs like Silicon Valley, thus produces increasingly sophisticated tools that align closely with the objectives of state surveillance and military modernization.17 This effectively blurs the distinction between civilian technological progress and the enhancement of state power projection and control capabilities.

2.3 Illustrative Case Studies

The convergence of commercial technology and state surveillance/military applications is exemplified by companies specifically operating in this dual-use space, as well as by the misuse of tools intended for legitimate purposes.

Palantir Technologies: Founded with early backing from the CIA's venture capital arm, Palantir specializes in big data analytics platforms designed to integrate and analyze vast, disparate datasets for intelligence, defense, and law enforcement clients.23 Its core platforms, like Palantir Gotham, are used by numerous US government agencies (CIA, DHS, NSA, FBI, CDC, various military branches) and foreign partners, including the Ukrainian military.23 Palantir explicitly markets its technology for national security and military purposes, including predictive policing (which has drawn criticism for potential bias) and, more recently, its Artificial Intelligence Platform (AIP).23 AIP is designed to integrate large language models (LLMs) and other AI tools into military operations, enabling operators to query intelligence data, generate potential courses of action, automate target analysis, and even control assets like drones or jamming systems.29 While Palantir emphasizes ethical guardrails and human oversight within AIP 29 , critics raise concerns about the potential for automating warfare, the abstraction of killing, and whether the "human in the loop" provides meaningful control or merely rubber-stamps AI recommendations.30 The company's business model inherently involves leveraging advanced data analysis techniques, often developed with commercial applications in mind, for state security purposes, embodying the dual-use challenge.

NSO Group (Pegasus Spyware): NSO Group, an Israeli cyber-arms firm, developed Pegasus, one of the most sophisticated pieces of spyware known.31 Sold exclusively to government clients for ostensibly fighting crime and terrorism, Pegasus can be covertly installed on target mobile phones (iOS and Android), often using "zero-click" exploits that require no user interaction.31 Once installed, it grants the attacker complete access to the device's data, including encrypted messages, call logs, contacts, location history, passwords, and can activate the microphone and camera for real-time eavesdropping.31 Despite NSO's claims of legitimate use, investigations by organizations like Citizen Lab and Amnesty International have repeatedly documented Pegasus being used by governments worldwide to target journalists, human rights activists, political dissidents, lawyers, and even heads of state.31 The US government placed NSO Group on an export blacklist due to these activities.32 However, the operation of Pegasus highlights global technological entanglement; lawsuits revealed that NSO utilized US-based servers (including some in California) to deploy the spyware against targets via platforms like WhatsApp.32 NSO has argued in court that targeting high-ranking government or military officials is legitimate intelligence gathering, broadening the potential scope of acceptable use beyond just criminals and terrorists.33 Pegasus demonstrates the existence of a global market for powerful, intrusive surveillance tools developed by private companies, lowering the barrier for states to acquire capabilities previously limited to major powers, and showing how even non-US actors can leverage US infrastructure for their operations.

These cases illustrate how technologies, whether data analytics platforms or targeted spyware, blur the lines between commercial innovation, national security, and potential human rights abuses. The inherent complexity and opacity of advanced AI models introduce further complications. The "black box" nature of neural networks, where decisions emerge from patterns in vast datasets rather than explicit human reasoning, makes their behavior difficult to fully predict or audit.19 Combined with vulnerabilities in training data – susceptibility to inherent biases or deliberate adversarial poisoning – deploying these AI systems in high-stakes surveillance or military contexts creates significant unpredictable risks.19 Errors could lead to catastrophic outcomes, such as the misidentification and targeting of civilians, or manipulation by adversaries in ways that are hard to detect or prevent.19 This moves beyond simple misuse into the realm of inherent unreliability and vulnerability embedded within the technology itself.

Chapter 3: Validating Concerns: Evidence Supporting Caution

The assertion that non-US territories should exercise caution when importing or utilizing US technology, particularly from Silicon Valley, finds support in several interconnected lines of evidence related to surveillance impacts, technological dependency, international legal conflicts, and documented abuses.

3.1 Impact of US Surveillance on Non-US Entities and Citizens

US surveillance laws like FISA Section 702 and Executive Order 12333 are explicitly designed or operationally function to collect intelligence from non-US persons located outside the United States.3 While Section 702 requires targeting non-US persons abroad, the nature of global communications means this "incidental" collection inevitably sweeps up vast quantities of data belonging to individuals worldwide who communicate with targets or simply use US-based platforms.4 EO 12333 allows for broad collection outside the US with even fewer constraints.4

This surveillance has tangible consequences. Beyond the direct collection of data, the knowledge or suspicion of being monitored can exert a chilling effect on freedom of expression and association, particularly for journalists, activists, researchers, and dissidents who may self-censor controversial or sensitive communications.5 Furthermore, the data collected, even if initially for foreign intelligence purposes, can potentially be used for other means, creating risks of discrimination, coercion, or selective enforcement against individuals or groups based on their communications, beliefs, or associations revealed through surveillance.34 Documented abuses within the US system, such as the FBI's improper querying of Section 702 databases for information on US citizens, including protestors, political donors, and crime victims, demonstrate that the potential for misuse is real.6 Given that oversight and legal protections are generally weaker for non-US persons 15 , it is highly plausible that similar or greater misuse occurs against foreign targets, though it is far harder to detect due to secrecy and the lack of legal standing for foreigners in US courts.34

3.2 Technological Dependency as a Geopolitical Vulnerability

Heavy reliance on technology sourced predominantly from a single foreign power, such as the United States, creates significant geopolitical vulnerabilities.35 This dependency extends beyond software to critical infrastructure, cloud services, semiconductor supply chains, and core digital platforms.20 Such dependence can be exploited as leverage in international disputes. A foreign power could potentially threaten to restrict access to essential technologies, mandate software updates containing hidden vulnerabilities, disrupt services, or use its control over data flows for economic coercion or intelligence advantage.37

Furthermore, dependency implies a lack of control over the security, integrity, and operational parameters of the technology stack.35 Non-US countries may find it difficult or impossible to fully audit proprietary foreign systems for backdoors or vulnerabilities, leaving them exposed to risks they cannot adequately assess or mitigate.40 This technological reliance can translate directly into reduced strategic autonomy, forcing nations to align their policies or tolerate actions (like surveillance) that contravene their own laws or interests, simply because the technological alternative is unviable or unavailable.36 Adopting US technology, therefore, often means implicitly importing US legal and surveillance norms, potentially undermining domestic laws and sovereignty even without explicit agreement.13 The use of US cloud providers, for instance, subjects stored data to the reach of the US CLOUD Act, regardless of the server's physical location or local data protection laws.11 This constitutes a de facto extension of US jurisdiction facilitated by technological integration.

3.3 International Law, Human Rights, and Criticisms of US Surveillance

US surveillance practices, particularly the large-scale collection programs revealed by Snowden, have faced significant criticism for potentially violating international human rights law, most notably the right to privacy enshrined in instruments like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).5 The ICCPR states that "no one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy".15 Critics argue that bulk collection programs under Section 702 and EO 12333 lack the necessary proportionality, necessity, and adequate oversight required by international standards.5

A key point of contention is the disparity in protections afforded to US persons versus non-US persons under US law.15 While US citizens have Fourth Amendment protections (though often debated in the surveillance context), non-US persons outside the US have far fewer legal safeguards against surveillance by US agencies.9 Furthermore, effective redress mechanisms for non-US individuals whose rights may have been violated by US surveillance are often lacking.15 Civil liberties organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) have consistently challenged the legality and constitutionality of US surveillance laws, arguing they represent government overreach and violate fundamental rights, including those under the First and Fourth Amendments.8 These criticisms highlight a perceived gap between US surveillance practices and internationally recognized human rights norms.

3.4 The Data Sovereignty Challenge: GDPR, the US CLOUD Act, and the Schrems II Fallout

The tension between US surveillance laws and foreign data protection regimes crystallized in the Schrems II decision by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in July 2020.41 The EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) imposes strict rules on the processing of personal data of EU residents and limits transfers of such data to countries outside the EU unless an "adequate" level of protection can be guaranteed.47

In Schrems II, the CJEU invalidated the EU-US Privacy Shield framework, which had previously facilitated transatlantic data flows.41 The court ruled that US surveillance laws, specifically citing FISA Section 702 and EO 12333, allowed US public authorities access to transferred data in ways that did not meet the GDPR's standards of necessity and proportionality, and that EU data subjects lacked effective judicial redress in the US against such surveillance.41

While the CJEU upheld the validity of Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) as a potential mechanism for data transfers, it added a crucial caveat: organizations using SCCs must conduct a case-by-case assessment (a Transfer Impact Assessment or TIA) to verify whether the laws and practices of the recipient country ensure adequate protection in line with EU standards.41 If the assessment reveals that the recipient country's laws (like US surveillance laws) undermine the protections offered by the SCCs, the data exporter must implement supplementary measures (e.g., strong encryption where feasible) to ensure equivalent protection. If adequate protection cannot be ensured even with supplementary measures, the transfer must be suspended or prohibited.42

This ruling created significant legal uncertainty and operational challenges for companies transferring data from the EU to the US, particularly those relying on major US cloud providers.14 It starkly highlighted the direct conflict between the GDPR's goal of protecting EU data from foreign government access and the US CLOUD Act's mandate allowing US authorities to compel access to data held by US providers, irrespective of its storage location.11 This places companies utilizing US-based cloud infrastructure for processing EU data in a potential legal bind, caught between conflicting legal obligations.11 The Schrems II decision is not merely a technical legal dispute; it reflects a fundamental divergence in values and legal approaches between the EU and the US regarding the balance between national security, law enforcement access, and fundamental rights to privacy and data protection, forcing other nations and global businesses to navigate this complex and contested landscape.41

Chapter 4: Counterarguments: The Case for Technological Engagement

Despite the significant risks associated with surveillance and dependency, a compelling case exists for continued engagement with US technology, particularly from Silicon Valley. The benefits offered are substantial, and the alternatives, including technological isolationism, present their own considerable challenges.

4.1 Acknowledged Benefits: US Technology as a Driver for Innovation, Efficiency, and Growth

US technology companies have been at the forefront of digital innovation, developing products and services that drive economic growth, enhance productivity, and address societal challenges globally.1 Adopting these technologies offers numerous advantages to non-US territories:

Increased Efficiency and Productivity: Technologies like cloud computing, AI-driven analytics, automation software, and advanced communication platforms enable businesses and public sector organizations to streamline operations, reduce costs, and improve service delivery.2 Examples include optimizing manufacturing processes, improving research administration through automated workflows 48 , enhancing agricultural yields via precision agriculture tools 50 , and facilitating remote work.49

Access to Innovation and Competitiveness: The US possesses a vibrant innovation ecosystem fueled by significant R&D investment.1 Engaging with this ecosystem provides access to cutting-edge technologies (AI, quantum computing, biotech) essential for maintaining global competitiveness.1 US tech can empower local innovators by providing powerful platforms and tools, such as cloud computing capabilities that allow enterprises to scale anywhere.2

Economic Growth and Development: US technology facilitates digital trade, connecting businesses to global markets and enabling the growth of service sectors like finance, education, and health.52 Digital tools can enhance financial inclusion, improve health outcomes through telehealth, and support sustainable development goals, such as using ICT solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.2 Investment in technology adoption is seen as a key driver for transforming economies.1

Global Integration and Standards: US technologies often underpin global communication and commerce networks.53 Participation allows for integration into these networks, benefiting from established standards and interoperability, although this also contributes to dependency risks.

The benefits derived from US R&D investments and the resulting technological advancements reverberate through all sectors of the global economy, making these technologies highly attractive, if not essential, for many nations.2

4.2 Perspectives on Risk Mitigation and Oversight

While criticisms of US surveillance are valid, proponents of engagement point to existing, albeit imperfect, oversight mechanisms and legal distinctions within the US system. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) reviews applications for surveillance under FISA, including Section 702 certifications.4 Independent bodies like the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) also review surveillance programs and make recommendations, sometimes agreeing that changes are needed.8 US law distinguishes between surveillance targeting non-US persons abroad (under authorities like Section 702 or EO 12333) and surveillance targeting individuals within the US or US persons abroad, which generally requires a warrant based on probable cause from the FISC or regular federal courts.6

Furthermore, major technology companies publicly state that they do not provide voluntary or "direct access" to government agencies but comply only with legally binding orders or subpoenas for specific accounts or identifiers.3 While gag orders often prevent disclosure of specific requests, some companies publish transparency reports indicating the volume of government demands they receive.7

Technical mitigation strategies, such as end-to-end encryption, are employed by many services to protect user data. However, the US government, particularly the Department of Justice and FBI, has persistently argued against strong encryption without "backdoors" or mandated access for law enforcement, creating tension with privacy advocates and security experts who argue such backdoors inevitably create vulnerabilities exploitable by criminals and foreign adversaries.46

4.3 The Perils and Practicalities of Technological Isolationism

Attempting to completely decouple from the US technology ecosystem ("technological autarky") presents significant practical challenges and potential downsides for most nations.40 Building competitive domestic alternatives across the entire technology stack, from semiconductors to cloud computing to AI, requires immense investment, a highly skilled workforce, and access to global markets and supply chains – resources few nations possess independently.1

Isolation risks cutting a nation off from the forefront of global innovation, leading to a technological lag that could severely hamper economic competitiveness and even national security in the long run.1 The interconnected nature of modern research, development, and supply chains makes true self-sufficiency extremely difficult to achieve.38 Even proponents of "technological sovereignty" often distinguish it from autarky, acknowledging the need for international collaboration and strategic interdependence.35

Moreover, seeking alternatives to US technology might lead nations towards other dominant players, such as China. However, relying on Chinese technology carries its own significant, and potentially greater, set of risks related to state surveillance, censorship, intellectual property theft, data security, and geopolitical leverage wielded by an authoritarian state.26 Therefore, isolationism may not only be impractical but could lead to dependencies on actors posing even more direct threats to national interests and democratic values.

The inherent tension is that the very characteristics making US technology powerful and beneficial – its scale, integration, advanced capabilities, and network effects 1 – are directly linked to the factors creating risk, namely the aggregation of data and centralized control by US companies subject to US surveillance laws.3 This creates a fundamental trade-off: maximizing the economic and efficiency gains from US technology may inherently increase exposure to US surveillance and geopolitical influence. Separating the benefits from the risks is extraordinarily difficult due to the integrated nature of the ecosystem. Consequently, a strategy of complete technological isolation appears largely unfeasible and potentially counterproductive for most nations. A more pragmatic approach likely involves managing the risks associated with dependency rather than attempting an impossible quest for complete self-sufficiency.40

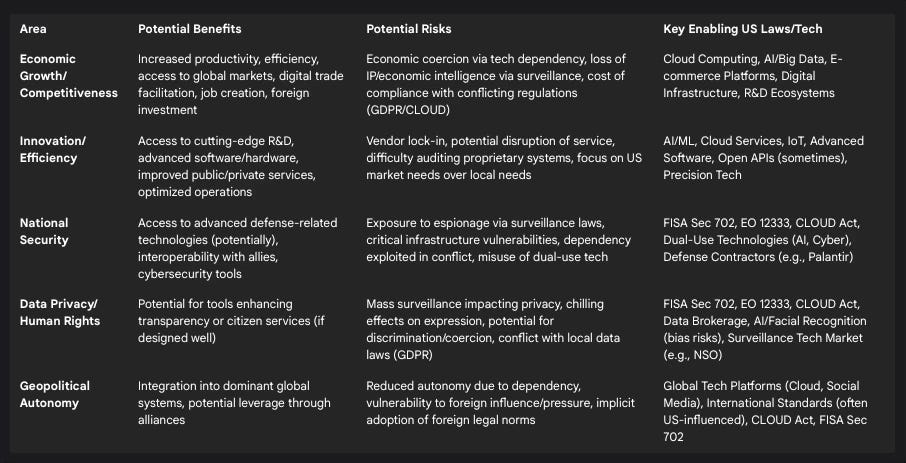

Table 2: Risk/Benefit Analysis of Adopting US/Silicon Valley Technology

Chapter 5: Charting a Course Towards Technological Sovereignty

Faced with the risks inherent in dependency on foreign technology ecosystems, particularly those of the US and China, many nations and regions are exploring strategies to achieve greater technological or digital sovereignty. This involves asserting more control over their digital infrastructure, data, and technological development pathways.

5.1 Defining and Pursuing Technological and Digital Sovereignty

Technological or digital sovereignty refers to the capacity of a state, nation, or region to have meaningful control over its own digital destiny – encompassing the data, hardware, software, standards, and infrastructure it relies upon.35 The core aim is to reduce unilateral dependencies on foreign powers, especially in critical technologies like AI, semiconductors, and cloud computing, thereby enhancing national security, economic competitiveness, and resilience against crises or external pressure.35

Crucially, technological sovereignty is generally not pursued as complete technological self-sufficiency or autarky, which is widely recognized as impractical in today's interconnected world.40 Instead, the goal is typically to achieve autonomy or minimize dependency in strategically vital areas, ensuring the state retains the ability to act according to its own priorities and values.35 This includes the ability to understand, apply, and potentially produce key technologies domestically; shape technological standards in line with democratic values; build a skilled workforce; and ensure that reliance on foreign expertise or imports does not compromise the state's ability to function or protect its citizens' rights.35 Motivations are multifaceted, ranging from safeguarding national security secrets and critical infrastructure to fostering domestic innovation, protecting citizen privacy from foreign surveillance laws like the CLOUD Act, and resisting geopolitical influence.35

5.2 Exploring Alternatives and Diversification Strategies

Several initiatives and national capabilities represent potential pathways or components for diversifying away from over-reliance on US (or Chinese) technology:

EU Efforts (GAIA-X, EuroStack): The European Union has made digital sovereignty a strategic priority.61 GAIA-X was launched by France and Germany in 2019 as an initiative to build a federated, secure, and interoperable data infrastructure based on European values like privacy, transparency, and data control.62 It aims to connect existing European cloud providers through shared rules and open standards, creating an alternative ecosystem less dependent on US hyperscalers (Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud) and less exposed to extraterritorial laws like the US CLOUD Act.62 However, GAIA-X has faced significant challenges: progress has been slow, hampered by internal divisions, a lack of consensus on the definition of sovereignty, and the sheer market dominance and investment power of US competitors.56 Critics note that the market share of EU cloud providers has actually shrunk since its inception.56 EuroStack represents a broader, more ambitious vision for a "full-stack" sovereign European tech sector, encompassing hardware, software, and data infrastructure, though its realization remains a long-term goal.39 Despite setbacks, these initiatives signal a clear political intent to foster European alternatives.63

India Stack: India has developed a unique model of digital public infrastructure known as India Stack.60 This consists of a set of open Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and digital public goods built on foundational layers: Aadhaar (biometric digital identity for over 1.3 billion residents), Unified Payments Interface (UPI, enabling real-time mobile payments at massive scale with minimal cost), DigiLocker (secure digital document storage), and the Account Aggregator framework operating under the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA, allowing consent-based data sharing).54 Built on principles of openness, interoperability, and scalability, India Stack was designed to address specific national needs like financial inclusion, reducing fraud in government benefit delivery, and digitizing services for a vast population.60 Its success has spurred significant innovation in the fintech sector and demonstrated how digital infrastructure developed as a public good can drive economic activity and empower citizens.54 The model, particularly its open-source identity component (MOSIP), is being explored or adopted by several other developing nations, offering a potential blueprint for building national digital ecosystems independent of dominant proprietary platforms.60 The success of India Stack suggests that focusing on specific national priorities and leveraging open, modular public infrastructure can be a viable path for nations not aiming to compete directly with global hyperscalers across all domains.

South Korea's Strengths: South Korea possesses significant technological capabilities as a world leader in advanced manufacturing, particularly in semiconductors (Samsung, SK Hynix), consumer electronics (LG), and automobiles (Hyundai).51 It has a highly developed digital infrastructure and strong domestic tech companies like Naver and Kakao that successfully compete with US giants in the local market, offering tailored services.68 South Korea is also investing heavily in areas like AI and next-generation communications.51 While closely allied with the United States, which may limit its pursuit of full technological independence, its capabilities make it a potential key partner in building more resilient global supply chains and contributing to alternative technological solutions, perhaps as a "critical technology wingman".51 However, it also faces challenges navigating US-China tech competition and local regulatory hurdles for foreign firms.51

Other National/Regional Initiatives: Other nations, such as Brazil and Estonia, are also developing their own digital public infrastructure initiatives, often inspired by models like India Stack or Estonia's own e-governance system, indicating a broader global trend towards seeking greater national control over digital systems.65

5.3 Viability Assessment: Challenges and Considerations

While alternative models and national capabilities exist, achieving meaningful technological sovereignty faces substantial hurdles. Building globally competitive alternatives to entrenched US technology giants requires enormous, sustained investment in R&D, infrastructure, and talent development.1 The network effects and economies of scale enjoyed by dominant players create high barriers to entry.2 Political will within nations or regions can be fragmented, and industrial policies aimed at fostering domestic champions can be difficult to implement effectively, as seen with some of the struggles of GAIA-X.56

Continue reading here (due to post length constraints): https://p4sc4l.substack.com/p/technologies-appearing-benign-could