- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Russia’s leverage over the United States is multifaceted, systemic, and likely to endure. It can be synthesized into five primary domains of influence; Energy Market Manipulation...

Russia’s leverage over the United States is multifaceted, systemic, and likely to endure. It can be synthesized into five primary domains of influence; Energy Market Manipulation...

...Financial System Disruption and De-Dollarization, Asymmetric Military Deterrence and Proliferation, Strategic Alliance Building and Counter-Hegemonic Coalition, Perpetual Hybrid Warfare.

Russia’s Levers of Global Influence: An Assessment of Economic, Military, and Geopolitical Power Projection

by Gemini 2.5 Pro, Deep Research. Warning, LLMs may hallucinate!

Section I: The Energy Fulcrum - Russia’s Global Oil and Gas Strategy

Russia’s status as a global power is inextricably linked to its immense energy resources. Its vast reserves of oil and natural gas are not merely commodities for export; they are foundational instruments of statecraft, providing the Kremlin with substantial economic revenue, geopolitical leverage, and the capacity to influence global markets. This section analyzes the core components of Russia’s energy strategy: its structural position as a top-tier producer, its strategic reorientation of trade flows in response to Western pressure, its co-leadership of the OPEC+ oil cartel, and the persistent, albeit reduced, energy dependence of Europe, which continues to complicate the Western alliance’s strategic calculus.

1.1 Russia’s Position as a Global Energy Superpower

The Russian Federation’s role in the international system is fundamentally underpinned by its status as an energy superpower. Quantitative analysis of its production and export capacity reveals an actor whose decisions have structural and immediate consequences for the global energy balance. In 2023, Russia was the world’s second-highest producer of both crude oil (including condensate) and dry natural gas, and the third-largest exporter of coal.1 Its total primary energy production reached approximately 60 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu) in that year, a figure that places it in the top echelon of global producers.1

This immense output is not just a feature of its economy; it is a critical component of the global supply chain. In 2021, prior to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s crude and condensate output of 10.5 million barrels per day (bpd) constituted 14% of the world’s total supply.2 Similarly, as the world’s second-largest producer of natural gas, its output of 762 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2021 was a cornerstone of global, and particularly European, energy security.2 The income derived from these exports is of paramount importance to the Russian state, forming the bedrock of its federal budget and enabling significant expenditures in other domains, most notably defense and security.2 In 2021, for instance, revenues from oil and natural gas comprised 45% of Russia’s federal budget.2 This deep integration into global energy markets means that any disruption to Russian supply, whether self-imposed or externally driven, inevitably creates price volatility and supply chain shocks, granting Moscow inherent geopolitical weight.3

1.2 The Strategic Pivot to Asia: Countering Western Sanctions

In response to the comprehensive sanctions imposed by the United States and its allies following the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia executed a rapid and remarkably successful reorientation of its energy trade from its traditional European markets toward Asia. This strategic pivot has been crucial in mitigating the economic impact of sanctions and has demonstrated the limits of Western economic coercion when major non-Western consumer markets remain accessible.

Before 2022, Europe was the primary destination for Russian energy exports. In 2020, European countries received 51% of Russia’s crude oil and condensate exports.6 By 2024, this share had plummeted to just 12%, and it fell further to 11% in the first half of 2025.6 This dramatic decline was offset by a corresponding surge in exports to Asia and Oceania. The region’s share of Russia’s crude exports rose from 41% in 2020 to 81% in 2024, with the People’s Republic of China and India absorbing the vast majority of these redirected flows.6

China, already a significant customer, solidified its position as the largest single importer of Russian crude, with imports averaging 2.2 million bpd in 2024.6 The most dramatic shift, however, occurred with India. Previously a marginal buyer, India’s imports of Russian crude skyrocketed from approximately 50,000 bpd in 2020 to an average of 1.7 million bpd in 2024, making it the second-largest recipient.6 This redirection was facilitated by Russia’s willingness to offer its crude at a significant discount to global benchmarks, an attractive proposition for large, price-sensitive, and energy-intensive economies.

This successful pivot has had profound strategic implications. First, it has ensured a continued and substantial flow of revenue to the Kremlin, blunting the primary economic weapon deployed by the West and enabling Russia to sustain its war economy.4 Second, it has deepened Russia’s economic and strategic ties with two of the world’s most important non-Western powers, reinforcing its narrative of a multipolar world and counteracting U.S.-led efforts at diplomatic and economic isolation. The sanctions regime, intended to weaken Russia, has thus inadvertently catalyzed the formation of new, powerful energy dependencies that run counter to U.S. strategic interests. This has led to complex second-order effects, such as the imposition of U.S. secondary tariffs on India for its continued purchases of Russian oil, creating a point of friction in the U.S.-India relationship—a partnership Washington views as critical for its Indo-Pacific strategy to counterbalance China.6 Russia, therefore, has gained an indirect lever through which it can introduce complications into the strategic calculations between Washington and New Delhi.

1.3 The OPEC+ Alliance: A Tool for Market Control and Geopolitical Leverage

A central pillar of Russia’s global energy strategy is its participation in the OPEC+ alliance. This group, which formalizes cooperation between the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and a coalition of non-OPEC producers, was established in late 2016.10 Its creation was a direct response to a structural shift in the global oil market: the U.S. shale revolution, which transformed the United States from the world’s largest importer into a major exporter, thereby diminishing OPEC’s unilateral ability to control prices.10 The inclusion of Russia, one of the world’s top three producers, was essential to forming a cartel with sufficient market power to manage global supply effectively.12

The actions of the OPEC+ agreement are largely driven by the close coordination between the two most influential producers in the group: Saudi Arabia, the de facto leader of OPEC, and Russia.12 Their shared interest lies in stabilizing the oil market and, frequently, in maintaining prices at a level high enough to support their respective national budgets.10 Through coordinated production cuts, the alliance can remove millions of barrels of oil from the global market, creating upward pressure on prices.14

This cooperation has evolved beyond a purely economic arrangement into a significant geopolitical tool. It provides a formal platform for high-level engagement between Russia and the major oil producers of the Middle East, most notably Saudi Arabia, thereby strengthening Russia’s position as a key player in the region and undermining U.S. efforts to isolate Moscow.10 The durability of this partnership has been tested and proven, persisting through a brief price war in 2020 and, more significantly, through the intense diplomatic pressure exerted by the U.S. and its allies on Saudi Arabia to increase production and abandon its cooperation with Russia following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.15

The alliance’s actions can run directly counter to U.S. interests. While the United States often seeks lower oil prices to curb domestic inflation and limit Russian state revenues, OPEC+ has demonstrated a willingness to prioritize the fiscal health of its members by implementing production cuts that keep prices elevated.10 This ability to influence a critical variable of the global economy gives Russia, in concert with its OPEC+ partners, a direct lever of influence that can impact U.S. economic stability and constrain its foreign policy options.

Table 1: Russia’s Key Energy Statistics (2020-2025). This table provides a quantitative overview of Russia’s energy production and the dramatic post-2022 shift in its export destinations.

1.4 Europe’s Lingering Dependency and the U.S. Dilemma

Despite a concerted and politically urgent drive to decouple from Russian energy, significant pockets of dependency remain within Europe. This lingering reliance, particularly in sectors where infrastructure is deeply entrenched or alternative supplies are limited, continues to grant Moscow a measure of leverage and creates strategic friction within the Western alliance.

While the European Union has made substantial progress in phasing out Russian crude oil and coal, the picture for natural gas is more complex.16 As of 2024, Europe remained Russia’s primary natural gas market, a reality dictated by decades of established pipeline infrastructure that cannot be easily or quickly replaced.1 Furthermore, EU sanctions have been less comprehensive regarding Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG), allowing imports to continue.1

Data from 2025 reveals a troubling trend: several EU member states, including some vocal supporters of Ukraine, have either maintained or increased their imports of Russian energy. Countries such as France, the Netherlands, Hungary, and Slovakia have continued to purchase Russian fossil fuels.8 Since 2022, EU countries have spent an estimated €213 billion on Russian energy, an amount that far exceeds the roughly €167 billion they have provided in military aid to Ukraine over the same period.8

This continued flow of payments to Russia undermines the collective Western strategy of economically pressuring the Kremlin. It has been a source of public frustration for U.S. leadership, which has highlighted the paradox of European nations effectively funding Russia’s war effort while simultaneously supporting Ukraine’s defense.8 This dynamic places the United States in a difficult position, forcing it to balance the strategic imperative of maintaining a united front against Russia with the pragmatic reality that some of its key allies cannot achieve complete energy independence in the short term.9 This dependency weakens the West’s collective negotiating position and provides Moscow with opportunities to exploit divisions within NATO and the EU.

Section II: Fortifying the Fortress - Financial Sovereignty and De-Dollarization

In parallel with its energy strategy, Russia has pursued a deliberate, long-term campaign to insulate its economy from Western financial pressure and to challenge the foundations of the U.S.-led global financial order. This “fortress economy” strategy rests on two main pillars: the systematic accumulation of physical gold as a sanction-proof sovereign asset and a proactive diplomatic effort, primarily through the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and new members) bloc, to promote de-dollarization and build an alternative financial architecture. These efforts are designed to enhance Russia’s financial sovereignty and reduce the efficacy of the United States’ most powerful non-military tool: its control over the global financial system.

2.1 The Strategic Accumulation of Gold: A Sanction-Proof Reserve

Russia’s pivot toward gold began in earnest after 2014, following the initial wave of Western sanctions imposed in response to its annexation of Crimea.19 Recognizing its vulnerability to financial measures targeting its foreign currency reserves, the Central Bank of Russia became one of the world’s most aggressive sovereign buyers of gold.19 By the time of the full-scale invasion in February 2022, Russia had amassed one of the largest gold stockpiles globally, with holdings of at least 2,322 tonnes, comparable to the reserves of France or China.19

The strategic brilliance of this strategy lies in the physical nature and location of the asset. Unlike its foreign currency reserves held in overseas accounts, Russia’s gold is stored in vaults on its own territory, placing it beyond the reach of Western asset freezes.19 This foresight proved critical when, in 2022, the United States and its allies immobilized an estimated $300 billion of Russia’s central bank assets denominated in dollars, euros, and other Western currencies.19 The gold reserves remained a liquid and sovereign store of value, providing a critical financial backstop.

This strategy yielded an additional, powerful benefit. The geopolitical instability and economic uncertainty unleashed by Russia’s invasion caused the global price of gold—a traditional “safe haven” asset—to surge.19 This price appreciation dramatically increased the value of Russia’s domestic gold holdings, with the rally in 2023-2024 driving the value of its reserves to over $302 billion.19 This effect created a perverse feedback loop: Russia’s own destabilizing actions made its primary sanction-proofing asset more valuable, thereby offsetting a significant portion—up to one-third—of the very assets the West had frozen as punishment.19

Beyond serving as a passive reserve, gold has become an active tool for circumventing sanctions. Russia has engaged in “gold-for-goods” trade, using its bullion to acquire hard currency, weapons, and other vital imports through hubs like the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Turkey, and Hong Kong, which then often facilitate re-export to China.19 This creates an alternative trade route that operates largely outside the purview of the formal, dollar-denominated financial system.

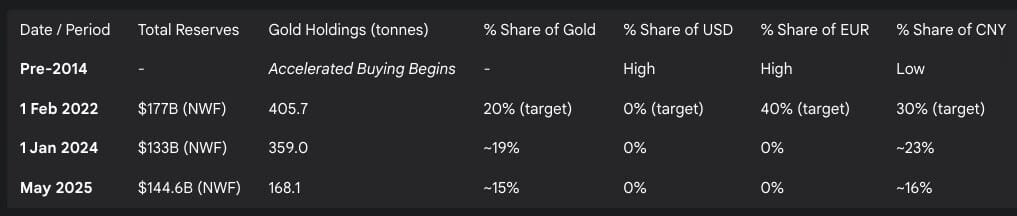

2.2 The National Wealth Fund (NWF): A Wartime Economic Buffer

The National Wealth Fund (NWF) of the Russian Federation serves as a key fiscal tool for managing the country’s resource wealth and providing macroeconomic stability. Funded primarily by surplus revenues from oil and gas exports, the fund’s official purposes include co-financing pensions and covering federal budget deficits during periods of low commodity prices.24 Since 2022, it has been repurposed into a critical wartime economic buffer, enabling the Kremlin to finance its massive increase in military spending and cushion the economy from the impact of sanctions.25

In a clear demonstration of its de-dollarization strategy, the NWF’s asset composition was radically restructured in the lead-up to and following the 2022 invasion. In the summer of 2021, the fund began divesting its U.S. dollar holdings, and after the invasion, it moved to close its euro holdings as well.25 Its liquid assets are now held almost exclusively in gold and Chinese yuan, insulating this pool of sovereign wealth from Western financial leverage.25 As of November 2024, the fund’s liquid assets consisted mostly of these two assets.25

The fund has been heavily drawn upon to plug the ballooning budget deficits caused by a combination of declining energy revenues (due to price caps and sanctions) and soaring military expenditures.25 Since the start of the war, Moscow has depleted nearly two-thirds of the fund’s pre-war liquid assets, with its value shrinking from $113.5 billion to just over $50 billion by late 2025.27 While this rate of expenditure is unsustainable in the long term, the existence of the NWF has provided the Kremlin with the crucial fiscal space to sustain its war economy for several years, far longer than many Western analysts initially predicted, thereby absorbing the immediate shock of sanctions and allowing the broader economy time to adapt to wartime conditions.27

Table 2: Evolution of Russia’s National Wealth Fund Asset Allocation (2022-2025). This table illustrates the strategic shift in the NWF’s liquid assets away from Western currencies toward gold and the Chinese yuan.

2.3 Leading the BRICS De-Dollarization Agenda

Russia has leveraged its position within the BRICS bloc to spearhead a global campaign aimed at reducing dependence on the U.S. dollar. The “weaponization” of the dollar through sanctions—most notably the freezing of Russia’s central bank assets and its partial exclusion from the SWIFT financial messaging system—served as a powerful catalyst for this movement.23 This demonstration of U.S. financial power sent a clear signal to other nations, particularly China and members of the “Global South,” of their own vulnerability to American economic coercion. This created a shared strategic interest in developing alternatives to the dollar-centric financial system.23

As the primary target of these measures, Russia has naturally assumed a leadership role in this de-dollarization effort, transforming its own punishment into a global rallying cry.30 Within the BRICS framework, Russia has successfully shifted the focus from the ambitious and likely impractical goal of creating a single common currency to a more pragmatic, two-pronged approach.29

The first prong is the promotion of bilateral trade using national currencies. This initiative has gained significant traction. In 2024, Russia reported that 90% of its trade with other BRICS members was conducted in their respective national currencies, completely bypassing the dollar.29 This trend extends beyond Russia; China and Brazil have established yuan-real trade arrangements, and India has conducted oil trades with the UAE in rupees.23 While these bilateral agreements do not yet constitute a unified assault on the dollar’s supremacy, they represent a steady, incremental erosion of its transactional dominance, particularly in commodity markets.29

2.4 Building an Alternative Financial Architecture: BRICS Pay and CRA

The second prong of the de-dollarization strategy involves the construction of a parallel financial infrastructure that can operate independently of U.S. control. The most significant of these initiatives is the development of “BRICS Pay,” a decentralized cross-border payment system intended to serve as an alternative to SWIFT.29 This system is being designed to integrate the existing national payment systems of member countries, such as Russia’s System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS) and China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS).29 A prototype of BRICS Pay was successfully demonstrated in Moscow in October 2024, marking a tangible step toward its eventual implementation.29

Complementing this payment system is the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), a $100 billion fund established in 2015.34 The CRA is designed to provide members with protection against global liquidity pressures and currency crises, functioning as an alternative to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).34 Together with the New Development Bank (NDB), another BRICS institution that provides financing for infrastructure projects, these initiatives represent a concrete effort to build a self-sufficient financial ecosystem for the non-Western world.34

While experts believe a fully functional and trusted alternative to the dollar and SWIFT is likely still years, if not decades, away, the political will and momentum behind these projects are significant.29 Each step toward their realization incrementally weakens the structural power of the U.S. dollar, directly challenging a core pillar of American global influence and its ability to project power through economic means.36

Section III: The Arsenal of Influence - Russia’s Military-Industrial Complex and Global Reach

The Russian military-industrial complex, known as the OPK (Oboronno-promyshlennyy kompleks), serves as a critical instrument of state power, extending far beyond its primary role of equipping the nation’s armed forces. It functions as a tool for geopolitical influence, a source of high-tech exports, and a laboratory for developing disruptive technologies designed to counter the military superiority of the United States and NATO. This section analyzes the complex state of the Russian defense industry, which is simultaneously showing signs of degradation under sanctions while producing highly advanced, asymmetric capabilities. It also examines how Russia strategically employs arms sales to cultivate long-term dependencies and create geopolitical leverage in key regions around the world.

3.1 The State of Russia’s Defense Industry: The “Deteriorating but Disruptive” Paradox

The Russian OPK presents a significant paradox. On one hand, there is mounting evidence of systemic weakness and degradation. A decade of targeted international sanctions, compounded by the immense material demands and losses of the war in Ukraine, has severely impacted its ability to produce and innovate.38 Analysis indicates the industry is experiencing “innovation stagnation,” with a heavy reliance on upgrading and refurbishing Soviet-era legacy systems rather than developing and mass-producing genuinely new, technologically advanced platforms.38 Recent data from late 2025 confirmed this trend, revealing a sharp slowdown and, in some cases, contraction in key defense-related manufacturing sectors that had previously driven Russia’s wartime economic growth.40 For example, the production of “fabricated metal products,” a key indicator, fell by 1.6% year-on-year in September 2025 after years of double-digit growth.42

On the other hand, the OPK has proven resilient enough to sustain a high-intensity, protracted war, producing equipment that is “good enough” to pose a constant threat on the battlefield.38 More strategically significant is its demonstrated ability to focus its limited high-tech resources on developing and deploying a narrow range of asymmetricand disruptive technologies. This is not an attempt to match the United States and NATO symmetrically across all domains of warfare. Instead, it is a calculated strategy to create and exploit specific vulnerabilities in Western military doctrine and capabilities, which are heavily reliant on technological superiority, network connectivity, and sophisticated defense systems.

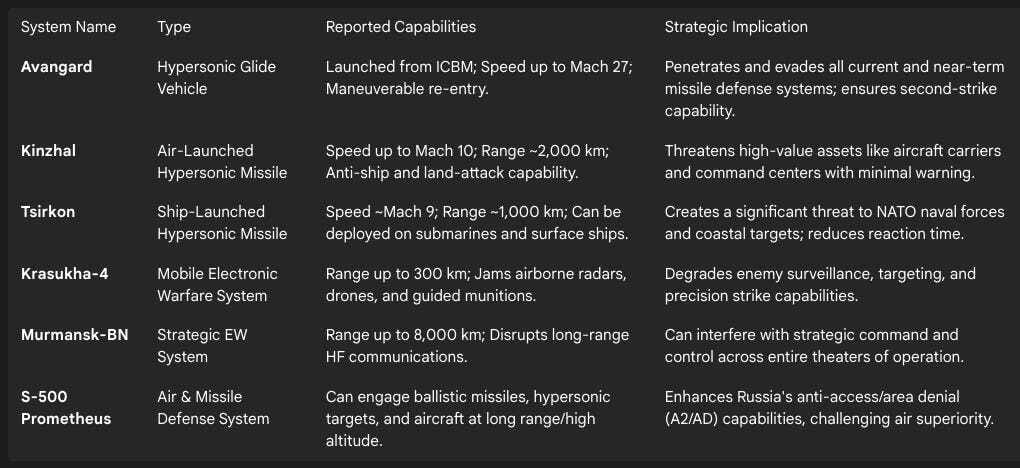

3.2 Asymmetric Technological Warfare: Hypersonics and Electronic Warfare

Two areas exemplify this strategy of targeted, asymmetric competition: hypersonic missiles and electronic warfare.

Hypersonic Missiles: Russia has achieved a significant first-mover advantage in the development and fielding of operational hypersonic weapons. These systems, which travel at speeds greater than Mach 5 and possess high maneuverability, are designed to defeat existing and near-future missile defense systems.43 Key systems in Russia’s arsenal include:

The Avangard: A hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) launched from an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), reportedly capable of speeds up to Mach 27. Its ability to make sharp, unpredictable maneuvers during its descent phase makes it nearly impossible for conventional anti-ballistic missile systems to intercept.46

The Kinzhal: An air-launched ballistic missile that can reach speeds of up to Mach 10. Launched from aircraft like the MiG-31K, it has a range of 2,000 kilometers and is intended to strike high-value, heavily defended targets such as aircraft carrier groups and command-and-control nodes.43

The Tsirkon: A ship-launched hypersonic cruise missile with a reported speed of Mach 9 and a range of 1,000 kilometers. Its deployment on a wide range of Russian naval vessels, including submarines, poses a significant threat to NATO naval forces and key coastal infrastructure, drastically reducing warning and reaction times.46

The strategic implication of these weapons is profound. They hold at risk the very assets that form the backbone of U.S. power projection—such as aircraft carriers and forward-deployed command centers—creating a powerful deterrent and a significant vulnerability that complicates U.S. and NATO operational planning.

Electronic Warfare (EW): Russia has long prioritized electronic warfare, viewing it as a critical asymmetric capability to counter the West’s reliance on networked communications, GPS navigation, and advanced sensor systems.47 Russia has developed and deployed a formidable array of ground-based EW systems that have been battle-tested in Syria and Ukraine.49 Notable systems include:

The Krasukha-4: A mobile EW system with a reported range of up to 300 kilometers, designed to jam airborne radars (such as those on surveillance aircraft and fighter jets), drone control links, and radar-guided munitions.49

The Murmansk-BN: A strategic, long-range communications jamming system capable of disrupting high-frequency (HF) radio signals over distances of up to 8,000 kilometers. This gives it the potential to interfere with strategic command-and-control networks across vast operational theaters.50

The effectiveness of these systems in Ukraine at neutralizing GPS-guided artillery shells and disrupting drone operations demonstrates their ability to degrade the precision and coordination that are hallmarks of modern Western warfare.49 By targeting this dependency, Russia’s EW capabilities represent a direct and potent threat to NATO’s operational effectiveness.

Table 3: Key Russian Advanced Military Systems and Assessed Capabilities. This table provides a concise summary of the disruptive technologies Russia is deploying to counter US/NATO military advantages.

3.3 Arms Exports as a Tool of Foreign Policy

Despite a significant decline in its global market share, Russia continues to leverage arms exports as a primary tool of foreign policy, using them to build influence, create long-term dependencies, and challenge U.S. partnerships in key strategic regions.

Global Market Position: According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Russia’s share of the global arms export market has fallen dramatically. It dropped from 21% in the 2015–2019 period to just 7.8% in 2020–2024, pushing Russia into third place behind the United States (43%) and a rising France (9.6%).53 This decline is attributable to several factors, including the impact of international sanctions, the need to divert production to meet the demands of its own war in Ukraine, and increased competition from other suppliers.53

Table 4: Global Arms Market Share Comparison (2015-2024). This table highlights the shifting dynamics in the global arms trade, showing Russia’s significant decline relative to the United States and France.

Strategic Sales and “Sticky” Dependencies: The raw numbers, however, do not capture the full strategic value of Russia’s arms sales. Moscow often targets countries and regimes where it can establish what can be termed “sticky” geopolitical dependencies.57 A major arms sale is not a one-time transaction; it initiates a multi-decade relationship encompassing training, maintenance, spare parts, software upgrades, and future munitions purchases. This embeds Russian influence deep within a partner nation’s defense establishment, making it difficult and costly to pivot to other suppliers.

Continue reading here (due to post length constraints): https://p4sc4l.substack.com/p/russias-leverage-over-the-united