- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

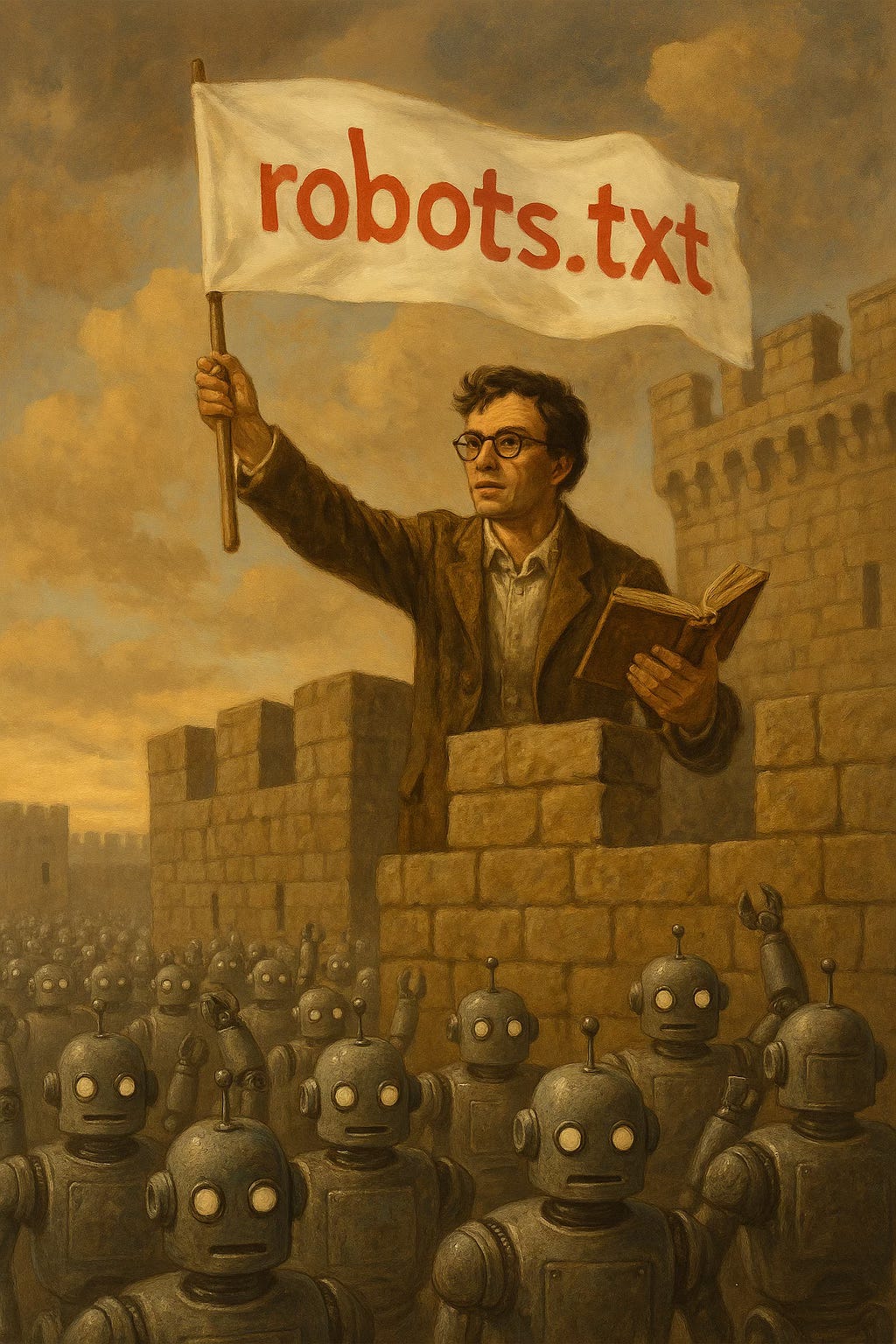

- Opt-out mechanisms such as robots.txt are inadequate, impractical, and fundamentally unfair.

Opt-out mechanisms such as robots.txt are inadequate, impractical, and fundamentally unfair.

Instead, the AI ecosystem must be grounded in enforceable licensing regimes that respect human expression as a matter of rights—not just data.

Why Machines Can’t Protect Creators from AI Exploitation: The Case Against robots.txt and Opt-Out Regimes

by ChatGPT-4o, based on “Machines don’t let machines do opt outs: why robots.txt won’t get it done for AI opt outs”.

As artificial intelligence systems rapidly consume the world’s creative outputs to fuel their training datasets, the debate over how to protect creators’ rights has reached a critical inflection point. Central to this debate is whether machine-readable opt-out tools like robots.txt are sufficient safeguards—or whether they function more as political theater than effective protection. Drawing from the Artist Rights Institute’s submission to the UK Intellectual Property Office and Chris Castle’s commentary, this essay argues that opt-out mechanisms such as robots.txt are inadequate, impractical, and fundamentally unfair. Instead, the AI ecosystem must be grounded in enforceable licensing regimes that respect human expression as a matter of rights—not just data.

The Illusion of robots.txt as a Rights Management Tool

At first glance, using tools like robots.txt to block AI crawlers may seem like a technical fix to a legal and ethical problem. However, as Chris Castle sharply critiques, these tools are premised on a dangerous assumption: that machines will abide by rules humans set in silence. The reality is more troubling. robots.txt files are frequently ignored by malicious or non-compliant crawlers, misconfigured due to complex syntax requirements, or circumvented through cached data, dynamic content, or unlisted scrapers. These limitations expose the fallacy of delegating rights management to machine protocols rather than law and human oversight.

What’s worse, Castle notes, is that this burden falls squarely on the creator—the person whose livelihood is at risk—not the AI developer or platform harvesting the data. This is not just a technical failure; it’s a structural inequity that privileges billion-dollar platforms over individual artists, musicians, and writers. “The difference between blocking a search engine and an AI scraper,” Castle warns, “is that one is inconvenient—the other is catastrophic”.

Opt-Out Schemes: Formalities in Disguise

The Artist Rights Institute expands this critique by dissecting the deeper legal implications of opt-out regimes. Their response to the UK IPO consultation firmly rejects the UK Government’s proposed text and data mining (TDM) exception that would allow AI training on copyrighted material unless creators explicitly “opt out.” The Institute calls this framework a thinly disguised formality, violating the Berne Convention’s prohibition against requiring creators to take proactive steps to enjoy protection of their works.

More importantly, they argue that such schemes introduce an “asymmetrical obligation”—placing the onus entirely on the rights holder while AI platforms, often flush with capital, continue scraping the internet without notice or consent. As seen in the notice-and-takedown regime, creators are left to police an ecosystem they had no say in designing. There’s no recourse, no government enforcement, and no meaningful deterrent against abuse.

AI’s Appetite and the Race to Legalize Infringement

Beyond the legal and technical dimensions, both documents explore a more disturbing pattern: the deliberate delay tactics used by AI platforms to cement their control over culture. The Artist Rights Institute traces a clear lineage from past episodes of mass digitization, such as Google Books, to today’s AI training methods. By exploiting legal grey areas and lobbying for new exceptions, tech companies aim to convert acts of copyright infringement into retroactively sanctioned business models. It’s the same playbook, they argue—just now at global scale.

This strategy, coupled with massive venture capital investments and lobbying pressure, is designed to create what they call a “de facto safe harbor.” As platforms scrape copyrighted works and expand their models, they’re betting that governments will either look the other way or change the law in their favor before enforcement catches up.

Copyright as a Human Right, Not a Regulatory Hurdle

Perhaps the most compelling moral argument advanced by the Artist Rights Institute is that copyright protections are not mere regulatory red tape—they are embedded in the very fabric of human rights. Citing Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Institute reminds policymakers that creators have the right to “the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author”.

When AI platforms claim that copyright enforcement hinders innovation, they are pitting automation against human dignity. But as the Institute argues, innovation cannot come at the cost of erasing the labor, identity, and livelihood of creators. An opt-out regime doesn’t just fail legally—it fails ethically.

Conclusion: Toward a Licensing-Based Future

The promise of AI must not come at the expense of the people whose works make intelligence—artificial or otherwise—possible. As both Castle and the Artist Rights Institute assert, governments must reject technical solutions like robots.txt and legal schemes built on opt-outs. Instead, a rights-respecting, licensing-based framework is essential to ensuring that human expression is not mined, monetized, and forgotten.

To paraphrase a striking line from the Institute’s submission: if an artist is more likely to get police protection for a stolen car than for the theft of their life’s work by an AI platform, then something has gone horribly wrong with the policy design.