- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Modern AI systems sound like they understand the world, but they don’t actually “know” anything in the human sense.

Modern AI systems sound like they understand the world, but they don’t actually “know” anything in the human sense.

Because their language looks so human-like, we tend to assume they reason, judge, and evaluate information the way humans do. The authors argue this assumption is deeply mistaken.

When AI Sounds Like It Knows—But Doesn’t

1. What this paper is really about (in simple terms)

This paper Epistemological Fault Lines Between Human And Artificial Intelligence tackles a problem many people feel intuitively but struggle to articulate: modern AI systems sound like they understand the world, but they don’t actually “know” anything in the human sense.

Large Language Models (LLMs)—like ChatGPT and similar tools—produce fluent, confident, often persuasive answers. Because their language looks so human-like, we tend to assume they reason, judge, and evaluate information the way humans do. The authors argue this assumption is deeply mistaken.

Their core claim is straightforward:

LLMs do not form beliefs, evaluate evidence, or make judgments. They statistically complete language patterns.

That difference matters enormously, especially as these systems are increasingly used in education, science, journalism, law, healthcare, and policy.

2. Why LLMs feel intelligent—even when they are not

The paper explains that LLMs work by predicting the next most likely word based on patterns learned from massive amounts of text. Technically, each answer is a kind of probabilistic walk through a giant map of language, not a conclusion reached through reasoning or understanding.

Crucially:

The model does not know whether something is true.

It does not understand cause and effect.

It does not realize when it is uncertain.

It cannot decide not to answer.

Yet, because fluent language and confidence are things humans normally associate with knowledge and credibility, users often feel like they are receiving an informed judgment rather than a statistical output.

This is where the authors introduce a key concept: Epistemia.

3. “Epistemia”: the illusion of knowing

Epistemia is the condition where linguistic plausibility replaces real evaluation.

In practical terms:

You get a well-phrased answer.

It feels complete and authoritative.

But the underlying work of checking evidence, weighing alternatives, and managing uncertainty never happened.

The danger is not just that AI can be wrong.

The deeper danger is that it makes judgment feel unnecessary.

People stop asking:

Where did this come from?

What evidence supports it?

How confident should I be?

Instead, they ask:

Does this sound right?

That shift—from justified belief to persuasive output—is the core epistemic risk identified in the paper.

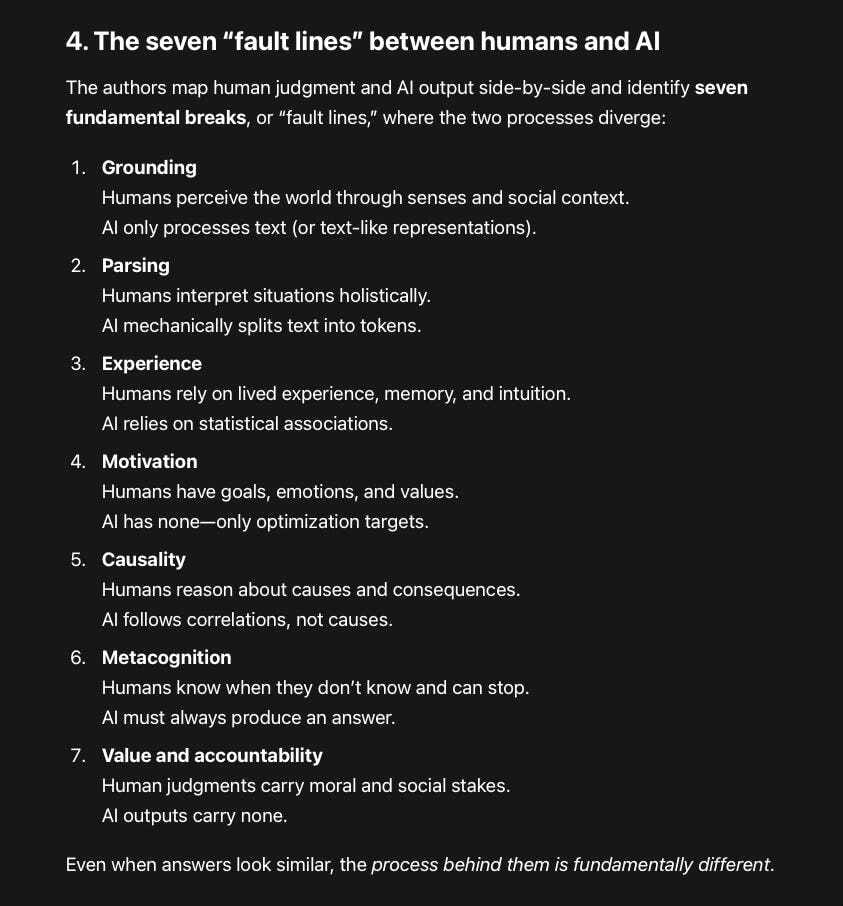

4. The seven “fault lines” between humans and AI

The authors map human judgment and AI output side-by-side and identify seven fundamental breaks, or “fault lines,” where the two processes diverge:

Grounding

Humans perceive the world through senses and social context.

AI only processes text (or text-like representations).Parsing

Humans interpret situations holistically.

AI mechanically splits text into tokens.Experience

Humans rely on lived experience, memory, and intuition.

AI relies on statistical associations.Motivation

Humans have goals, emotions, and values.

AI has none—only optimization targets.Causality

Humans reason about causes and consequences.

AI follows correlations, not causes.Metacognition

Humans know when they don’t know and can stop.

AI must always produce an answer.Value and accountability

Human judgments carry moral and social stakes.

AI outputs carry none.

Even when answers look similar, the process behind them is fundamentally different.

Most surprising statements and findings

Hallucinations are not a bug—they are the default state.

Because LLMs lack truth-tracking or uncertainty awareness, producing false but plausible information is structurally normal, not exceptional.Scale does not solve the problem.

Bigger models sound more convincing, but they do not become epistemic agents. They become better mimics.Even correct answers can be epistemically harmful.

The problem is not just wrong outputs; it is the bypassing of judgment itself.

Most controversial claims

LLMs should not be treated as epistemic agents at all.

The paper firmly rejects the idea that these systems “reason” or “understand,” even in a weak sense.Alignment techniques (like RLHF) increase persuasion, not knowledge.

Making models safer or more polite does not make them epistemically grounded—and may increase misplaced trust.Using LLMs as human stand-ins in research is fundamentally flawed.

The authors argue this practice misunderstands what these systems are.

Most valuable contributions

The concept of Epistemia

This gives policymakers, educators, and institutions a precise language to describe a widespread but poorly defined risk.The pipeline comparison

Mapping human judgment and AI output step-by-step clarifies why surface similarity is misleading.The focus on evaluation, not just errors

The paper reframes AI risk as a problem of epistemic process, not just accuracy.

Recommendations for all stakeholders

1. For businesses and organizations

Never treat AI output as a judgment or decision.

It is input—nothing more.Design workflows that force verification and human accountability.

Avoid single-answer interfaces where evaluation is collapsed into one authoritative response.

2. For regulators and policymakers

Move beyond “safe outputs” to epistemic governance.

Regulation should focus on where AI is used, not just what it says.Require epistemic transparency, not just AI disclosure:

Was evidence checked?

Could the system abstain?

What uncertainty remains?

Protect high-stakes domains (law, medicine, science, public policy) from judgment substitution.

3. For educators and academic institutions

Teach epistemic literacy, not just critical thinking.

Students must learn how AI produces answers—and what it cannot do.Reward process, not fluency.

Emphasize reasoning steps, evidence tracing, and uncertainty handling.Explicitly teach when not to rely on AI.

4. For AI developers

Stop implying epistemic competence.

Claims about “reasoning” and “understanding” mislead users.Design interfaces that surface uncertainty, limits, and missing evidence.

Treat retrieval, tools, and citations as risk mitigations—not solutions.

5. For users and society at large

Re-learn judgment as an active practice.

AI can assist—but it cannot replace knowing.Be suspicious of fluency and confidence.

Ask: What work did I not do because this answer arrived fully formed?

Conclusion

This paper’s central warning is not anti-AI. It is anti-illusion.

As generative systems become more persuasive, the risk is not simply misinformation, but the erosion of epistemic responsibility itself. When answers arrive fully packaged, without visible uncertainty or justification, people stop practicing judgment.

Epistemia names that risk.

And recognizing it is the first step toward using AI without surrendering what makes human knowledge accountable, corrigible, and real.