- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

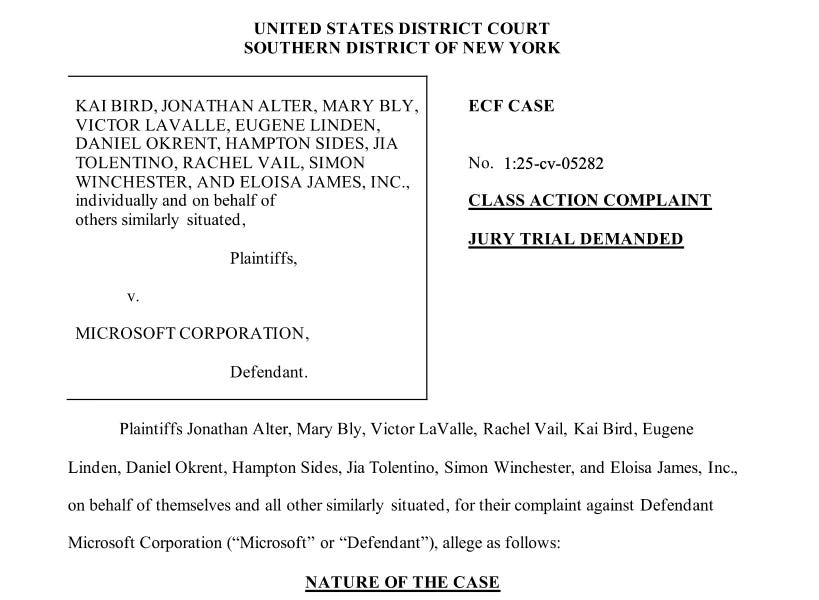

- James Bird, a journalist & nonfiction author, filed this lawsuit against Microsoft and OpenAI, alleging that their AI products—specifically Copilot and ChatGPT—were trained on his copyrighted works...

James Bird, a journalist & nonfiction author, filed this lawsuit against Microsoft and OpenAI, alleging that their AI products—specifically Copilot and ChatGPT—were trained on his copyrighted works...

...without permission and are capable of outputting near-verbatim excerpts from his books. The lawsuit introduces a more detailed and direct evidentiary link between input and output.

Essay on Bird v. Microsoft (Case No. 1:25-cv-05282, S.D.N.Y., June 24, 2025)

by ChatGPT-4o

Introduction

The case of Bird v. Microsoft marks another significant moment in the growing tide of litigation targeting generative AI developers for alleged copyright infringement, unfair competition, and failure to credit or compensate content creators. James Bird, a journalist and nonfiction author, filed this lawsuit against Microsoft and OpenAI, alleging that their AI products—specifically Copilot and ChatGPT—were trained on his copyrighted works without permission and are capable of outputting near-verbatim excerpts from his books.

This lawsuit shares DNA with cases like Tremblay v. OpenAI, Kadrey v. Meta, and Getty Images v. Stability AI, but also introduces a more detailed and direct evidentiary link between input (Bird’s books) and output (AI-generated content). Below is an analysis of the grievances, the strength of the evidence, the case’s prospects, and implications for AI developers.

Grievances

Bird asserts the following primary claims:

Direct Copyright Infringement

Bird alleges that Microsoft and OpenAI copied his works into their training datasets and that outputs of their models contain identical or nearly identical text from his books—specifically citing The Good Drone and Talk of the Town.Vicarious and Contributory Infringement

The complaint alleges that Microsoft profits from Copilot and OpenAI’s outputs while having both the right and ability to supervise or prevent the infringing conduct.Violation of the DMCA (§ 1202)

Bird claims that Microsoft and OpenAI stripped copyright management information (CMI), such as by removing his name and publisher details, thereby breaching Section 1202 of the DMCA.Unfair Competition (N.Y. common law)

Bird accuses the defendants of misappropriating the “labor, skill, and expenditure” involved in creating his books, thereby competing unfairly in the nonfiction information market.Deceptive Business Practices (N.Y. GBL § 349)

The complaint includes claims that Microsoft and OpenAI mislead the public by implying that AI-generated summaries or content are original or neutral, when in fact they’re derived from copyrighted sources like Bird’s.

Quality of the Evidence

The strength of Bird’s complaint lies in the specificity of its evidence:

Bird provides concrete side-by-side comparisons of passages from his books and the outputs of ChatGPT and Copilot, illustrating nearly verbatim reproduction, including factual claims, structure, and narrative.

The complaint notes that Bird’s books were available in formats likely to be included in training datasets (e.g., on websites known to be scraped).

There is detailed temporal linkage, such as references to GPT-3 and GPT-4 capabilities in relation to Bird's books, showing that the models trained on or at least absorbed protected text prior to certain dates.

The inclusion of source URLs for where Bird's works were scraped or cached (e.g., cached .edu domains) strengthens the argument that the works were in the training data.

Compared to earlier suits—like Tremblay v. OpenAI, where plaintiffs failed to provide direct output matches—Bird’s evidence is arguably more compelling. This is especially true if the court accepts the outputs as “substantially similar” and if the AI models are shown to have memorized and regurgitated protected expression rather than merely learning ideas or styles.

Legal Standing and Chances of Success

While the complaint is well-crafted and arguably stronger than many others, Bird still faces several legal hurdles:

Fair Use Defense

Microsoft and OpenAI are likely to argue that the use of Bird’s books for training was fair use. However, the direct reproduction of verbatim or near-verbatim outputs may undermine that defense—especially if the outputs are not transformative or compete with the original market.Substantial Similarity

Courts will scrutinize whether the outputs are not just similar in ideas but in protected expression. Bird’s examples may meet that bar more clearly than other plaintiffs have.DMCA § 1202

This claim requires evidence that the defendants intentionally removed CMI knowing it would promote infringement. If the training process involved stripping metadata or names (as alleged), this claim could survive.Unfair Competition and State Law Claims

These face preemption challenges under the Copyright Act, unless Bird can clearly show the claims are “extra elements” beyond pure copying. Courts have been inconsistent here.

Bird’s odds are better than those of most plaintiffs in this space. He has direct evidence, an individual authorship claim, and fact-based allegations that avoid speculative or class-wide generalizations. That said, overcoming the fair use defense will remain a steep challenge—particularly if courts continue to view AI training as analogous to reading.

Comparisons to Other Cases

Bird’s case avoids some of the procedural pitfalls and evidentiary gaps seen in these earlier cases. It also features a single plaintiff with a focused factual record—unlike class actions which struggle with representational adequacy and commonality.

Recommendations for AI Developers

Bird’s lawsuit should serve as a wake-up call to Microsoft, OpenAI, and other AI developers. Regardless of the legal outcome, the reputational and financial risks are rising. Developers should:

Enhance Transparency

Publicly disclose what data was used in training, or at least commit to excluding known copyrighted material without licenses.Improve Provenance Controls

Ensure that AI outputs do not memorize or reproduce entire passages of copyrighted text. Use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to allow citation and licensing pathways.Offer Opt-Out and Licensing Schemes

Develop standardized licensing models or opt-out registries for creators—possibly using frameworks like C2PA for content provenance.Avoid Metadata Stripping

If training on materials with copyright information, ensure that metadata isn’t removed unless legally necessary and justified.Monitor Outputs Proactively

Implement guardrails to detect and block high-verbatim outputs that risk copyright infringement.

Conclusion

Bird v. Microsoft presents one of the most well-substantiated AI copyright lawsuits filed to date. It avoids the speculative overreach of some class actions and backs its claims with detailed comparisons of original and AI-generated text. While fair use remains a formidable defense, Bird’s specific and tangible evidence may move the needle—especially as courts become more familiar with the technical mechanics of AI models.

The lawsuit should not just be viewed through the lens of litigation risk, but as a signal to the AI industry: transparency, licensing, and responsible training practices are no longer optional. Developers who ignore these lessons may soon face not just legal liability, but growing public and regulatory backlash.