- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- How the semiconductor industry—once the purest symbol of globalisation—has become an arena of geopolitical coercion, legal improvisation, and strategic mistrust.

How the semiconductor industry—once the purest symbol of globalisation—has become an arena of geopolitical coercion, legal improvisation, and strategic mistrust.

Nexperia, a century-old European chipmaker with deep roots in Philips and NXP, was crushed between the incompatible logics of the United States, China, and Europe.

A Company Caught Between Empires: Nexperia and the End of Innocent Globalisation

by ChatGPT-5.2

The NRC reconstruction of Nexperia in niemandsland (Nexperia in no-man’s-land) is not merely a corporate drama. It is a case study of how the semiconductor industry—once the purest symbol of globalisation—has become an arena of geopolitical coercion, legal improvisation, and strategic mistrust. The authors argue that Nexperia, a century-old European chipmaker with deep roots in Philips and NXP, was crushed between the incompatible logics of the United States, China, and Europe. Based on both the detailed reporting in the article and wider public evidence, this assessment is largely correct—though it also reveals uncomfortable truths about European strategic naïveté and corporate governance failures.

What the Article Shows, in Plain Terms

Nexperia produces “boring but vital” chips: diodes, transistors, and power semiconductors that go into cars, appliances, and industrial electronics. These are not cutting-edge AI accelerators, but without them modern economies stop. The article demonstrates three core dynamics:

Ownership without sovereignty

When Nexperia was sold in 2017 to Chinese investors, neither the Netherlands nor the EU had an effective foreign-investment screening regime. At the time, these chips were not seen as strategically sensitive. That assumption proved false. Once US–China tech decoupling accelerated, Nexperia suddenly mattered—not because of what it could do, but because it could not be easily replaced.Geopolitics overrides corporate logic

From the US perspective, Chinese ownership—even indirect, even partial—triggers suspicion. From China’s perspective, industrial assets on its territory are leverage. From Europe’s perspective, Nexperia was simultaneously “too Chinese to trust” and “too important to lose.” The result was paralysis, followed by emergency intervention.A leadership model that broke under pressure

The authors portray Wing, Nexperia’s Chinese owner-CEO, as both a product and a victim of this system: an aggressive, centralising founder who believed scale, speed, and integration would save the company. Instead, his attempt to pull Nexperia closer to China—commercially and operationally—triggered precisely the state backlash he hoped to avoid.

These are not speculative claims. They are corroborated by the sequence of events: UK forced divestment of Newport Wafer Fab, German refusal of subsidies, US Entity List escalation, Dutch emergency legislation, and finally China’s export intervention that froze the Dongguan plant.

1. Was Nexperia genuinely “in no man’s land”?

Yes. The concept is analytically sound. Nexperia was neither allowed to function as a Chinese company nor protected as a European one. This is consistent with broader patterns in strategic industries:

US export-control policy increasingly treats ownership structure, not product category, as the risk signal.

China treats industrial assets as instruments of national resilience, not neutral market actors.

Europe intervenes late, legally, and defensively—often only when crisis becomes unavoidable.

Nexperia fell precisely into the gap between these systems.

2. Was the Dutch government’s emergency intervention justified?

From a rule-of-law and proportionality perspective, the use of a 1952 emergency law is extraordinary. But from a strategic-dependency perspective, it is understandable. Comparable precedents exist: Germany blocking chip and robotics acquisitions, France asserting “economic sovereignty,” and the US invoking national security for far less systemically important assets.

The authors are right to frame this as a failure of prior policy, not merely a heavy-handed present response. Had investment screening, governance conditions, and contingency planning existed earlier, the crisis would not have required emergency powers.

3. Was Wing the villain?

The article is careful—and correct—not to reduce the story to personal misconduct alone. Wing’s management style, conflicts of interest (notably WingSkySemi), and governance centralisation clearly worsened the situation. But structurally:

Any Chinese-controlled entity supplying Western automotive supply chains would have faced escalating scrutiny after 2022.

Any attempt to “re-nationalise” production into China would have been interpreted as technology leakage, regardless of intent.

Wing’s error was believing that globalisation still functioned on commercial logic alone. It does not.

What the Case Reveals About the Semiconductor World

Beyond Nexperia, the ordeal illustrates five deeper truths:

“Legacy chips” are strategic chips

Power semiconductors and discrete components are now as geopolitically sensitive as advanced logic nodes, because they are harder to substitute quickly and underpin physical infrastructure.Corporate governance is now a national-security issue

Board composition, reserved matters, IP firewalls, and capital controls are no longer internal questions. They determine whether states trust firms to operate at all.Europe pays for being late

Europe enjoyed the benefits of open capital flows without building defensive institutions. When the geopolitical weather changed, it had to improvise—at great economic and reputational cost.China’s leverage is asymmetric but real

The Dongguan export stop shows that China can weaponise “boring” manufacturing chokepoints just as effectively as rare earths or batteries.Companies are now collateral damage by default

The US explicitly treated Nexperia as “collateral damage” of broader export rules. This is not accidental; it is a feature of contemporary economic statecraft.

Future Consequences of the Nexperia Ordeal

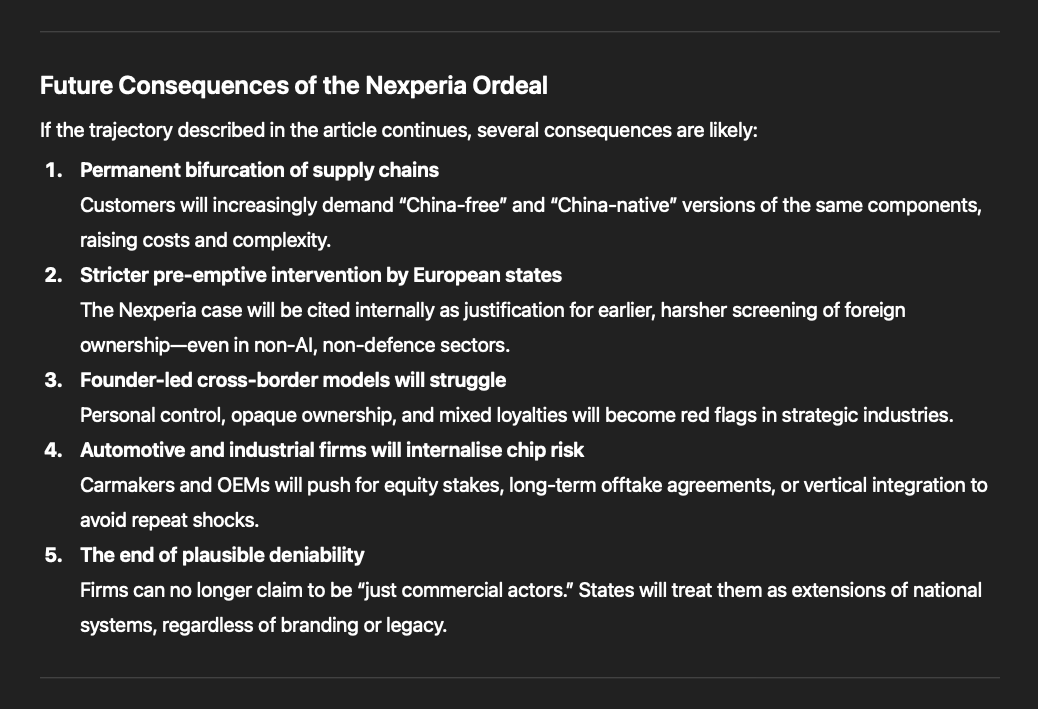

If the trajectory described in the article continues, several consequences are likely:

Permanent bifurcation of supply chains

Customers will increasingly demand “China-free” and “China-native” versions of the same components, raising costs and complexity.Stricter pre-emptive intervention by European states

The Nexperia case will be cited internally as justification for earlier, harsher screening of foreign ownership—even in non-AI, non-defence sectors.Founder-led cross-border models will struggle

Personal control, opaque ownership, and mixed loyalties will become red flags in strategic industries.Automotive and industrial firms will internalise chip risk

Carmakers and OEMs will push for equity stakes, long-term offtake agreements, or vertical integration to avoid repeat shocks.The end of plausible deniability

Firms can no longer claim to be “just commercial actors.” States will treat them as extensions of national systems, regardless of branding or legacy.

Conclusion

The authors of the NRC reconstruction are fundamentally correct: Nexperia did not fail because it made the wrong products or served the wrong customers, but because it existed in a world that no longer tolerates strategic ambiguity. The tragedy is not that governments intervened—but that they did so too late, with too few tools, and at too high a cost.

Nexperia’s story is therefore not an anomaly. It is a warning: in the age of technological rivalry, neutrality is no longer a viable business model.