- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- GPT-4o: Dahl’s empirical study delivers a sobering message—LLMs still fall short when it comes to automating even the most mechanical legal procedures. This study offers an essential reality check.

GPT-4o: Dahl’s empirical study delivers a sobering message—LLMs still fall short when it comes to automating even the most mechanical legal procedures. This study offers an essential reality check.

While LLMs can mimic legal language and even cite real cases from memory, they struggle when required to follow complex legal procedures with precision. Don’t blindly trust AI for legal formatting.

Procedural Limits of AI: Why Large Language Models Still Can’t Say Goodbye to the Bluebook

by ChatGPT-4o

Introduction

The paper "Bye-bye, Bluebook? Automating Legal Procedure with Large Language Models" by Matthew Dahl investigates a critical but often overlooked question: Can today's leading AI models reliably follow the rigid procedural rules that structure legal practice, specifically the notoriously complex citation system outlined in the Bluebook? While AI holds promise for transforming the legal profession, Dahl’s empirical study delivers a sobering message—LLMs still fall short when it comes to automating even the most mechanical legal procedures.

This essay unpacks the findings of the paper in accessible language, highlights the most surprising and controversial results, and concludes with recommendations for stakeholders including lawyers, AI developers, law schools, and regulators.

What the Paper Says – In Simple Terms

The Bluebook is a 500+ page manual that dictates how legal professionals in the U.S. must cite court cases, statutes, and other legal documents. It's incredibly detailed and often seen as overly complex, yet it remains a gold standard in legal practice.

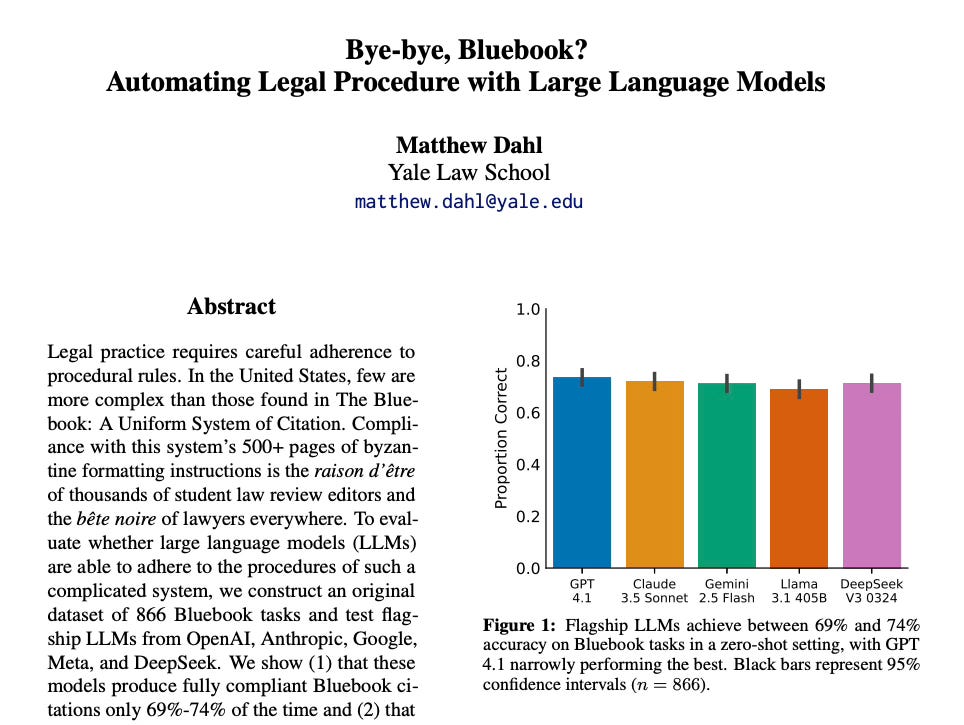

To see if AI could handle this task, Dahl created a dataset of 866 citation tasks and tested five of the most advanced AI models from OpenAI (GPT-4.1), Anthropic (Claude 3.5), Google (Gemini 2.5), Meta (Llama 3.1), and DeepSeek. He checked how well they could generate correct Bluebook citations in a zero-shot setting (no examples provided) and after giving one model the full rulebook to refer to.

The findings:

Without examples, AI only got 69%-74% of the citations completely correct.

Even when given the full rulebook, accuracy only rose to 77%.

Many errors weren’t just stylistic—they were serious mistakes that could mislead judges, lawyers, or clients.

In other words, while LLMs can mimic legal language and even cite real cases from memory, they struggle when required to follow complex legal procedures with precision.

Most Surprising, Controversial, and Valuable Findings

Surprising:

The best models (Claude and GPT-4.1) performed well on case law citations but much worse on statutes, administrative regulations, and secondary sources.

Models often succeeded not because they understood the rules but because they had memorized the citation of famous cases—performance dropped sharply when case details were slightly altered.

Controversial:

Even when AI was given the entire 90,000-token rulebook to work with (via Google’s Gemini), performance barely improved. This challenges the tech industry’s claim that larger context windows in LLMs enable reliable long-form reasoning.

The study indirectly critiques the AI hype in legal tech, cautioning that if LLMs can’t master citation formatting, their suitability for more complex legal tasks (e.g. legal drafting, adjudication) is highly questionable.

Valuable:

This is one of the first rigorous tests of whether LLMs can follow legal procedure—not just understand legal content.

The study offers a valuable benchmark for legal tech developers and researchers focused on evaluating LLM performance beyond superficial outputs.

Implications and Recommendations for Stakeholders

For Lawyers and Law Firms:

Don’t blindly trust AI for legal formatting or procedural compliance. Even small citation errors can undermine credibility or lead to sanctions.

Use AI as a drafting assistant, but not as a replacement for human review in procedural tasks.

For Legal Educators and Law Students:

Training in Bluebook compliance remains relevant—even in the age of AI.

Law schools should teach students how to work effectively with AI tools, including how to verify and correct their outputs.

For AI Developers and Vendors:

Current general-purpose LLMs are inadequate for high-stakes procedural tasks. Fine-tuning on legal procedural corpora or developing legal-specialist models may be necessary.

Claims about long-context reasoning must be tested on real-world procedural tasks, not abstract benchmarks.

For Courts and Regulators:

Courts should remain skeptical of filings that rely entirely on AI-generated citations. Enhanced scrutiny may be needed to detect fabricated or incorrect authorities.

Regulators should consider requiring clear disclosures when AI tools are used in legal drafting or filings, especially in pro se contexts.

Conclusion: The Dangers of AI Overreach in Law

This study offers an essential reality check. If today's most advanced language models can’t reliably cite legal cases, statutes, or sources—even with the rules in hand—then they are far from ready to take on more complex, procedural-heavy legal roles. Over-reliance on AI without human oversight could compromise legal integrity, mislead courts, and damage trust in the justice system.

Ultimately, if the legal system is built on rules—and those rules are inflexible, intricate, and unforgiving—then any AI designed to participate in that system must be judged not just on eloquence but on procedural precision. Until that threshold is met, the Bluebook stays—and so does the need for the human lawyer.