- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Gemini: The danger of societal decay isn't a Luddite fantasy; it is a plausible outcome, not because tech is inherently evil, but because our current mode of tech development is dangerously imbalanced.

Gemini: The danger of societal decay isn't a Luddite fantasy; it is a plausible outcome, not because tech is inherently evil, but because our current mode of tech development is dangerously imbalanced.

It's driven by ideology of exponential growth & narrow logic of instrumental reason, without maturation of the wisdom, ethical foresight and social cohesion required to manage its immense power.

The Janus Face of Progress: Technological Ascent and the Question of Humanistic Decline

by Gemini 2.5 pro, Deep Research. Warning, LLMs may hallucinate!

Part I: The Unquestionable Ascent - Charting the Vector of Technological Progress

The contemporary era is defined, above all, by the breathtaking velocity of technological change. This progress is not a matter of subjective perception; it is an empirically verifiable phenomenon, measurable in the exponential growth of our computational power, the global saturation of our information networks, and the dawning of revolutions in artificial intelligence and biotechnology. To comprehend the central tension of our time—the relationship between this technological ascent and the state of our humanity—one must first grasp the sheer scale, speed, and, most importantly, the underlying character of this progress. It is a trajectory that has moved beyond a mere sequence of inventions to become a self-perpetuating ideology, a goal actively pursued with global resources, shaping our world in its image.

Defining and Measuring Technological Progress

At its core, technological progress can be measured through various lenses. In economics, it is often quantified by productivity, which increases when fewer inputs, such as labor and capital, are required to produce a unit of output.1 While productivity growth in some developed countries has shown signs of slowing since the 1970s, this macroeconomic view belies a more fundamental and explosive trend in the technological substrate that underpins the modern world: information technology.1

The most potent metric of this progress is captured by Moore’s Law. Coined by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965, it began as an observation that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit (IC) was doubling approximately every two years with minimal rise in cost.2 This empirical relationship, however, is not a law of physics.4 Its significance lies in its transformation from a passive observation into a “motivating objective” and a “self-fulfilling prophecy” for the entire semiconductor industry.3 For nearly six decades, this projection has served as a guiding principle, a target that global corporations have poured immense resources into meeting, continually innovating to overcome the physical challenges of shrinking components to the size of atoms.3 This concerted, goal-oriented drive to maintain an exponential rate of improvement reveals a crucial aspect of modern technological development: it is not a natural, passive unfolding but a constructed and relentlessly pursued objective, driven by powerful economic and competitive forces. The very pace of our progress is an ideological choice, a decision to prioritize the exponential growth of computational capacity above other potential values.

This dynamic is further illuminated by Wright’s Law, a principle formulated in 1936 which holds that progress increases with experience, meaning each percent increase in cumulative production yields a fixed percentage improvement in efficiency.7 Research from MIT and the Santa Fe Institute found that both Moore’s Law and Wright’s Law are superior formulas for predicting the pace of technological advancement, with information technologies demonstrating the most rapid improvement.7 This confirms that the domains seeing the most intense production and investment are also those seeing the fastest progress, reinforcing the idea of a self-perpetuating cycle of development.

A Century of Transformation: Key Technological Revolutions

The abstract metrics of progress find their tangible expression in a series of cascading technological revolutions that have fundamentally reshaped society in little more than a single human lifetime.

The Computer Age: The theoretical groundwork for modern computing was laid by Alan Turing’s 1936 concept of a “Universal Machine”.8 This vision began to materialize with the development of the first general-purpose electronic digital computers, such as the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) in the 1940s.8 However, the true revolution was catalyzed by a series of hardware innovations. The invention of the transistor at Bell Labs in 1947 replaced bulky and unreliable vacuum tubes, leading to more advanced digital computers.10 This was followed by the creation of the first silicon integrated circuit, or “chip,” in 1958, which allowed for the miniaturization of electronic components.9 Finally, Intel’s release of the first commercially available microprocessor in 1971 placed an entire central processing unit onto a single chip, enabling the development of the personal computer and the subsequent proliferation of digital technology into every facet of life.8

The Information Age & The Internet: While the theoretical origins of the internet date back to the 1960s, its birth as a global network can be marked by the 1983 standardization of the Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP) and the introduction of the Domain Name System (DNS).8 Yet, it remained the domain of specialists until 1991, when Tim Berners-Lee launched the World Wide Web, making the internet accessible to the public through a graphical interface.8 The rate of adoption was staggering. In 1990, estimates suggest that only half a percent of the world’s population was online.12 By the year 2000, less than 7% of the world was connected.12 Yet, by 2017, the halfway point was crossed, with 50% of the global population online.12 During the five years leading up to 2018, an average of 640,000 people went online for the first time every single day.12 By 2024, an estimated 5.5 billion people, representing over 63% of the world’s population, are now internet users.12 This rapid expansion has fundamentally transformed communication, commerce, politics, and the very nature of information itself.

The AI Revolution: The field of artificial intelligence was formally founded at the 1956 Dartmouth Conference, built on the conceptual work of pioneers like Alan Turing.14 Early decades saw foundational developments, such as the first chatbot, ELIZA, in 1966, and the rise of “expert systems” in the 1980s.14 A significant public milestone was reached in 1997 when IBM’s Deep Blue chess computer defeated world champion Garry Kasparov.14 However, the current AI surge began in the 2010s, driven by breakthroughs in deep learning and neural networks. The success of the AlexNet architecture in a 2012 image recognition competition marked a turning point, demonstrating the power of deep learning.15 This led directly to the development of today’s Large Language Models (LLMs), with OpenAI’s GPT-3 (2020) and its successor GPT-4 (2023) demonstrating an astonishing ability to understand and generate human-like text, images, and code.14 Generative AI is now being integrated into workflows across nearly every industry, representing another exponential leap in technological capability.16

The Biotechnology Revolution: Running in parallel with the digital revolution is an equally profound transformation in our ability to understand and manipulate the code of life itself. The discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA by Watson and Crick in 1953 provided the foundational knowledge.17 This culminated in the Human Genome Project, a monumental international effort that produced a “rough draft” of the human genome in 2000 and was completed in 2003, providing a complete map of our genetic makeup.17 More recently, the development of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology in 2010 has provided scientists with a tool to make precise modifications to DNA, akin to a molecular “find and replace” function.8 This technology holds revolutionary potential for treating genetic diseases, improving agriculture, and fundamentally altering our relationship with our own biology.19 Further milestones, such as the cloning of Dolly the sheep in 1997 and the creation of the first synthetic bacterial genome in 2010, underscore our growing mastery over the biological realm.17

Collectively, these revolutions demonstrate a clear, undeniable, and accelerating vector of technological progress. This progress is not merely additive; it is synergistic, with advances in one domain (e.g., AI and computing power) accelerating breakthroughs in others (e.g., genomics and materials science). The result is a society built upon a foundation of ever-increasing technical capacity, a trajectory that shows no signs of abating and continues to redefine the limits of the possible.

Part II: The Disquieting Descent? - An Audit of Contemporary Humanity

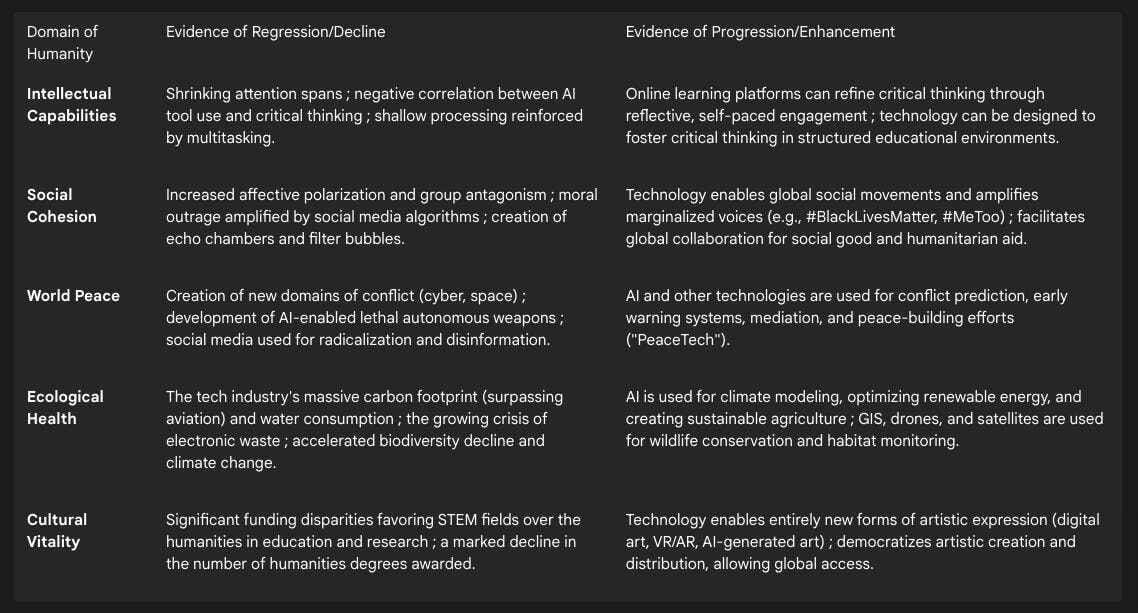

The narrative of relentless technological advancement, while factually robust, stands in stark contrast to a growing sense of unease about the state of our collective humanity. The user’s query posits a regression in our intellectual capabilities, social cohesion, ecological stewardship, and cultural vitality. This section will systematically audit this claim, presenting a balance sheet of evidence for both decline and advancement across these critical domains. The analysis reveals a complex and often contradictory picture, where technology frequently appears as both the agent of decay and the instrument of salvation. This duality suggests that technology is not a simple cause but a powerful, non-neutral amplifier of pre-existing human tendencies and societal structures, and that our very reliance on it to solve the problems it helps create may itself be a symptom of a deeper ideological malaise.

Table 1: A Balance Sheet of Humanistic Indicators in the Technological Age

The Fractured Mind: Attention, Cognition, and Critical Thinking in the Digital Milieu

A primary concern is that the very tools designed to augment our intelligence may be subtly eroding our core cognitive faculties. There is substantial evidence to support this apprehension. Research by Gloria Mark at the University of California, Irvine, has documented a measurable shrinkage in attention spans over the last two decades. Direct observation of information workers showed that the average duration of attention on any single screen fell from two and a half minutes in 2004 to just 75 seconds by 2012.22 This fragmentation of focus is a direct consequence of an environment saturated with digital distractions and notifications.

The pervasive practice of digital media multitasking appears to have neurophysiological consequences. Studies suggest a link between heavy media multitasking and reduced gray matter density in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a brain region vital for cognitive control, emotional regulation, and judgment.25 This constant task-switching reinforces neural pathways geared toward “shallow and rapid processing” at the expense of those that facilitate deep, sustained concentration.25 The result is a brain that becomes, in effect, “programmed to be distracted,” finding it increasingly difficult to engage in tasks requiring prolonged focus, even in the absence of external interruptions.25

Furthermore, there is a growing concern about “cognitive offloading,” where the habit of delegating mental effort to external aids like AI tools diminishes our own analytical capabilities. Studies have found a significant negative correlation between frequent AI tool usage and critical thinking abilities, a trend particularly pronounced in younger participants.23 As Patricia Greenfield of UCLA argues, our society is experiencing a shift where visual skills are improving at the expense of skills associated with print literacy, such as reflection, analysis, and imagination.63

However, the relationship between technology and cognition is not uniformly negative. The same digital environment offers powerful tools for education. Online learning platforms provide a “student-centered” experience, allowing learners to proceed at their own pace and revisit complex material as needed.64 The asynchronous nature of online discussions can lead to higher-quality dialogue, as it affords participants time for reflection and the formulation of more thoughtful responses compared to the immediacy of face-to-face conversation.64 Some research indicates that, when properly designed, educational technology—from interactive digital media to project-based learning using online resources—can significantly improve students’ critical thinking skills.27 This duality suggests that technology’s impact on cognition is not inherent to the technology itself, but is contingent on the context of its use—whether it is designed to capture and fragment attention for commercial purposes or to structure and deepen it for educational ones.

The Polarized Heart: Empathy, Collaboration, and the Fraying of the Social Fabric

We live in a paradox: a world more interconnected than ever, yet seemingly more divided. Technology, particularly social media, sits at the heart of this contradiction. A growing body of research links social media usage to a rise in “affective group polarization”—not merely disagreement on policy, but an intense, visceral dislike and distrust of those in opposing political groups.30

One of the key psychological mechanisms driving this phenomenon is the digital amplification of “moral outrage.” This potent emotional cocktail of anger and disgust, triggered by perceived moral violations, is exceptionally effective at generating engagement on social media platforms.31 Algorithmic systems designed to maximize user engagement inadvertently prioritize and spread the most radical and polarizing content, creating a feedback loop that can lead to group antagonism and even the dehumanization of opponents.31 This is compounded by the formation of “echo chambers” or “filter bubbles,” where selective exposure to ideologically consistent content reinforces existing beliefs and reduces opportunities for meaningful engagement with different perspectives.32 Exposure to cross-cutting information, rather than fostering understanding, can trigger defensive mechanisms and solidify ideological rigidity, especially in the hostile and disinhibited environment of online political discourse.32

Yet, these same technological platforms have proven to be revolutionary tools for social and political emancipation. They have provided unprecedented avenues for organizing, raising awareness, and effecting change on a global scale.33 The Black Lives Matter movement, for instance, effectively used social media to circulate videos of police violence and mobilize nationwide protests against systemic racism, leading to widespread demonstrations and policy reforms.33 Similarly, the #MeToo movement gained global momentum through social media, challenging the silence surrounding sexual harassment and holding powerful individuals accountable.33 In this context, technology acts as a megaphone for marginalized voices and a coordination tool for collective action, fostering a form of global collaboration and solidarity that was previously unimaginable.34 Technology, then, does not create social division or solidarity; rather, it provides a powerful infrastructure that can amplify both, scaling up our capacity for tribalism and our capacity for unified action in the pursuit of justice.

Continue reading here (due to post length constraints): https://p4sc4l.substack.com/p/gemini-the-danger-of-societal-decay