- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Courts, rights holders, and regulators are converging on a coherent legal doctrine that views AI training as copying subject to copyright, not an exempt activity.

Courts, rights holders, and regulators are converging on a coherent legal doctrine that views AI training as copying subject to copyright, not an exempt activity.

Refusal to license does not magically transform unlicensed copying into fair use. A real, functioning licensing market exists, projected to grow from $6 billion today to $52.4 billion within a decade.

Copyright Law Draws a Line in the Sand: What Disney, AAP, and the ROSS Litigation Signal for the Future of AI

by ChatGPT-5.1

Introduction

By late 2025, the legal landscape for AI has decisively shifted. Two documents crystallize this turning point:

The MLex report describing Disney, Paramount, Sony, Universal, and Warner Bros. urging a US appeals court not to create an “AI-specific” fair use exception and to reaffirm that copyright owners may license — or refuse to license — their works as they see fit.

The AAP’s amicus brief in Thomson Reuters v. ROSS, which similarly insists that AI developers cannot use “technological innovation” as a talisman to justify mass unlicensed copying, and emphasizes the emergence of a multibillion-dollar AI-training licensing market.

Together, these filings mark a pivotal moment: courts, rights holders, and regulators are converging on a coherent legal doctrine that views AI training as copying subject to copyright, not an exempt activity. The implications for AI litigation — and for AI builders — are enormous.

I. The Most Important Elements Across the Documents

1. No “AI-Specific” Fair Use Exception

Hollywood studios warn that a new, AI-tailored version of US fair use would imperil the copyright system. Their brief argues:

Creators decide whether to license or not; refusal to license does not magically transform unlicensed copying into fair use.

A court-created carve-out for AI would “disrupt fair-use law” for all creative sectors.

This directly rebuts the AI industry narrative that AI training is categorically transformative.

2. AI Training Is Recognized as a Market — and an Enforceable Right

The AAP brief emphasizes:

Delaware was “first in the nation” to recognize that usurping copyrighted materials for AI training is infringement, not innovation.

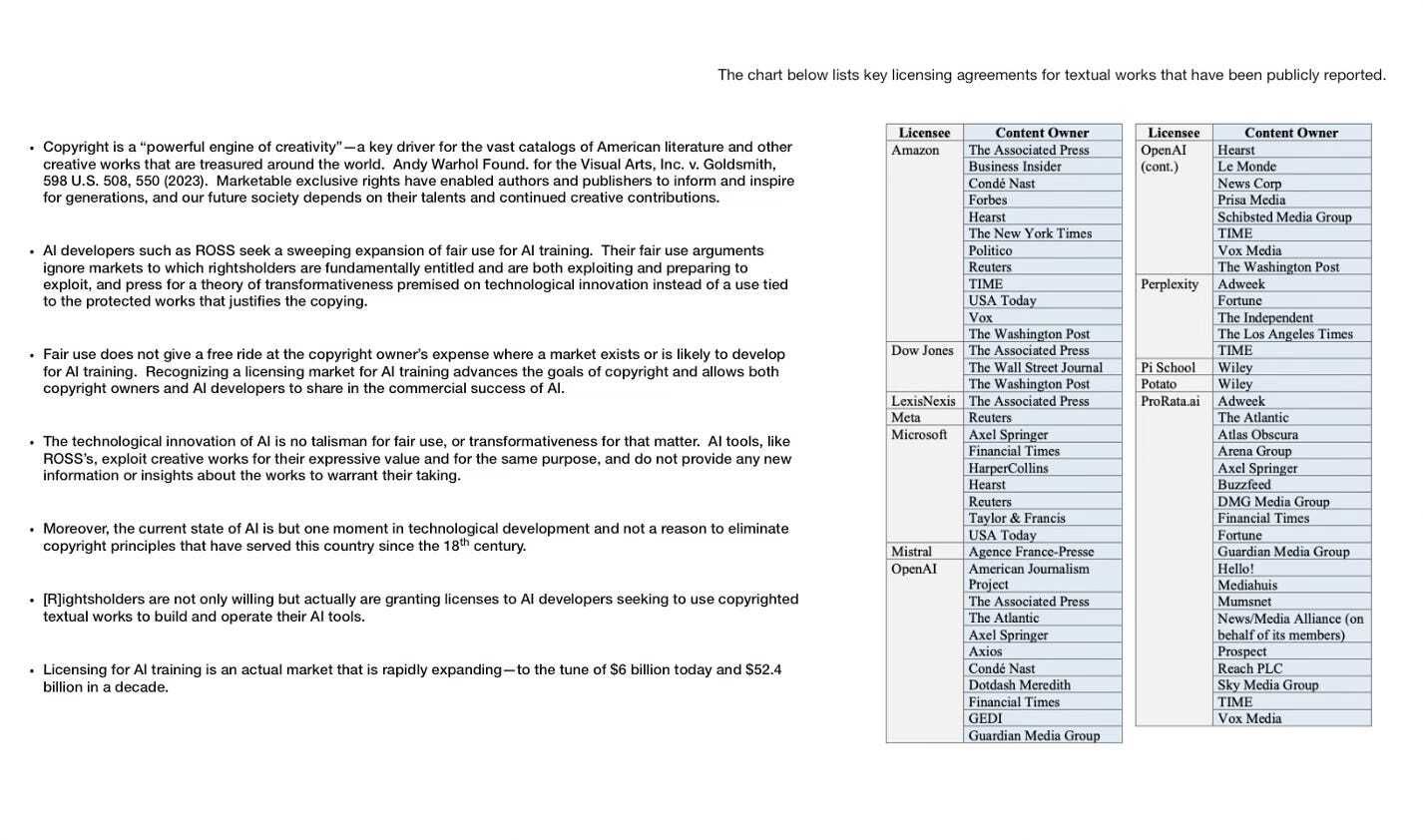

A real, functioning licensing market exists, projected to grow from $6 billion today to $52.4 billion within a decade.

Where a market exists — or is expected to develop — fair use cannot override the rights of copyright owners.

The AAP even includes a detailed table of current AI-training licensing deals, covering OpenAI, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Mistral, Perplexity, and more — evidence that the market is healthy and expanding.

3. Technological Innovation Alone Does Not Equal “Transformative Use”

AAP stresses:

AI tools “exploit creative works for their expressive value… for the same purpose” as the original works.

Innovation is not a justification: AI “does not provide any new insights about the works” that would justify mass copying.

This aligns with the Supreme Court’s Warhol decision: transformation must be meaningfully tied to the copyrighted work, not merely a new technology layered on top.

4. Direct Market Substitution Is a Fatal Blow to Fair Use

In Thomson Reuters v. ROSS, the district court found:

The AI product directly competed with Westlaw’s legal research service.

This showed clear market harm, tipping the fair-use balance decidedly against ROSS.

This is one of the most important holdings for future AI litigation: AI systems that functionally replace a copyright-protected database face steep legal risks.

5. Copyright Law Applies to AI the Same Way It Applies to All Other Technologies

Both documents highlight continuity, not novelty:

Copyright has survived every technology transition since the 18th century.

AI is another in a long line of innovations that must comply with existing law.

Courts should avoid “sweeping exceptions” that would hollow out rights owners’ incentives.

This rebuts arguments that AI represents such a qualitative shift that copyright should bend around it.

II. What These Developments Mean for Ongoing AI Litigation (US and Beyond)

1. Plaintiffs Are Now Coordinating Across Industries

The combination of Hollywood (MLex report), book publishers (AAP), academic publishers, journalism organizations, and software/database owners signals a unified industry coalition asserting that:

AI training requires permission;

AI ingestion equals copying;

Licensing markets are legitimate and growing;

AI output markets compete with their core businesses.

Future defendants will face well-funded, cross-sector coalitions filing aligned briefs.

2. Courts Are Increasingly Skeptical of “Transformative AI” Arguments

After Warhol, courts evaluate transformation based on purpose, meaning, and market substitution — not technological novelty. AI companies’ argument that embedding copyrighted text into model weights is “non-expressive” or “non-substitutive” is losing traction.

The ROSS decision provided a template:

Input copying + model output substituting for the protected work = infringement.

3. Courts Are Normalizing “AI Training” as a Recognizable, Licensable Use Case

The presence of:

AAP’s $6bn → $52bn market projection, and

The table of dozens of existing licensing deals

will heavily influence courts’ analysis of market harm.

If a functioning market exists, the legal test requires courts to protect it.

4. “Non-Availability of a License” No Longer Helps AI Companies

Studios make the point sharply:

A copyright owner’s choice not to license cannot justify unlicensed copying.

Fair use cannot be forced into existence simply because a rightsholder refuses.

This directly attacks arguments used by Stability AI, Midjourney, LAION, and others claiming “there was no market when we trained.”

5. AI Developers Face Heightened Expectations of Traceability and Compliance

These filings interact with broader developments:

EU AI Act training-data disclosure

US Executive Order on AI safety and provenance

FTC statements on deceptive training-data claims

Courts asking for chain-of-custody data for training corpora

Increased litigation over synthetic “derivative” datasets

Together, they point toward a regulatory-judicial framework of transparency + licensing.

III. What AI Makers Must Do to Adapt to This Legal Reality

This evolving legal doctrine is not anti-AI; it defines the rules of engagement. AI companies must shift from a “train first, justify later” posture to a rights-respecting, documentation-first paradigm.

1. Establish Clean, Verifiable Training Pipelines

Courts increasingly require:

Documentation of sources

Proof of license or public domain status

Chain of custody logs

Separation of licensed vs. unlicensed data

Ability to delete or retrain (“right to relief”)

AI makers must build compliance architecture similar to:

supply-chain tracking

software provenance frameworks (e.g., SBOMs)

2. Purchase Licenses Proactively — Not After Litigation Begins

The AAP’s chart shows the new reality:

Licensing is the norm, not the exception.

Leading AI companies (OpenAI, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, Mistral, Perplexity) are already doing it because:

It reduces litigation risk

It strengthens enterprise trust

It provides competitive access to higher-quality datasets

It protects downstream customers from copyright liability

3. Stop Relying on “Transformative Use” as a Primary Defense

Courts are moving toward:

treating training as a commercial use

rejecting “purely functional copying” arguments

considering model outputs as potential substitutes

Instead of litigating around transformation, AI makers should:

prioritize licensing

implement filtering

develop retrieval-based or rights-aware architectures (e.g., RAG with licensed corpora)

develop contracts with indemnification frameworks

4. Build “Rights-Aware” AI Models

Modern architectures can incorporate:

content tagging (e.g., W3C C2PA provenance)

licensed-only corpus partitions

opt-out respect mechanisms

differential output controls

attribution/reference linking

AI models should know what data they can legally use, not merely what data they have seen.

5. Anticipate Global Convergence

This US litigation aligns with:

EU AI Act transparency rules

UK IPO work on text/data mining exceptions

Japan’s reconsideration of its permissive TDM regime

China’s draft rules on training-data compliance

Australia’s pending inquiry into fair use and AI

Global alignment is trending toward:

permission-first

traceability

licensing markets

publisher participation

AI companies must prepare for multi-jurisdictional compliance.

Conclusion

The AI sector has reached its copyright inflection point. The Hollywood studios’ brief (MLex) and AAP’s amicus filing converge around a clear message:

AI does not sit outside copyright. Training is copying. Licensing is the path forward. Courts will not reshape fair use to save AI companies from the consequences of their ingestion practices.

This is not a retreat from innovation; it is the normalization of AI within existing commercial expectations. Licensing markets are booming, courts are becoming consistent, and publishers are coordinating. The next generation of AI models will succeed not by outrunning regulation but by integrating rights-respecting frameworks into their architecture from day one.

AI makers that adapt early — with clean datasets, licensed corpora, transparent pipelines, and responsible safeguards — will be the ones that thrive in the next phase of the AI economy.