- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Claude: These maps should be appreciated not as precise historical documentation but as visual arguments about political possibility...

Claude: These maps should be appreciated not as precise historical documentation but as visual arguments about political possibility...

...documents that capture both what was and what their creators hoped might be.

Mapping Global Solidarity: An Analysis of Four Cold War Era Interconnection Charts

An Examination of Historical Networks and Their Contemporary Relevance

by Claude. Warning, LLMs may hallucinate!

[Note: where Claude may assume too much about the nature and (time/date of) origin of these maps, the other LLMs had great difficulty both reading the maps properly AND not (regularly) mixing up both the analyses and the maps]

Introduction

The four historical [sic] maps examined in this essay represent remarkable artifacts from a pivotal period in twentieth-century global politics. Created [sic] during the Cold War era, these interconnection charts document the complex web of relationships among newly independent nations as they navigated the treacherous waters between competing superpower blocs. Each map tells a distinct story about different aspects of Third World solidarity, anti-colonial resistance, and the quest for an alternative path in international relations.

These maps are more than simple geographic representations—they are visual arguments about political possibility. They demonstrate how activists, scholars, and political movements sought to understand and articulate connections between disparate struggles for liberation, economic independence, and self-determination. The first map charts the global architecture of the Non-Aligned Movement and its relationship to Cold War power structures. The second focuses on African political groupings and their internal debates about continental unity. The third examines international communist and socialist networks. The fourth explores intellectual and organizational connections centered around Third World solidarity and anti-imperialist movements.

This essay will analyze each map individually, examining the historical connections they depict, evaluating the accuracy and significance of these relationships, and assessing whether the connections shown reflect genuine historical linkages or represent aspirational networks that never fully materialized. Through this analysis, we can better understand both the achievements and limitations of Third World solidarity movements during the Cold War era.

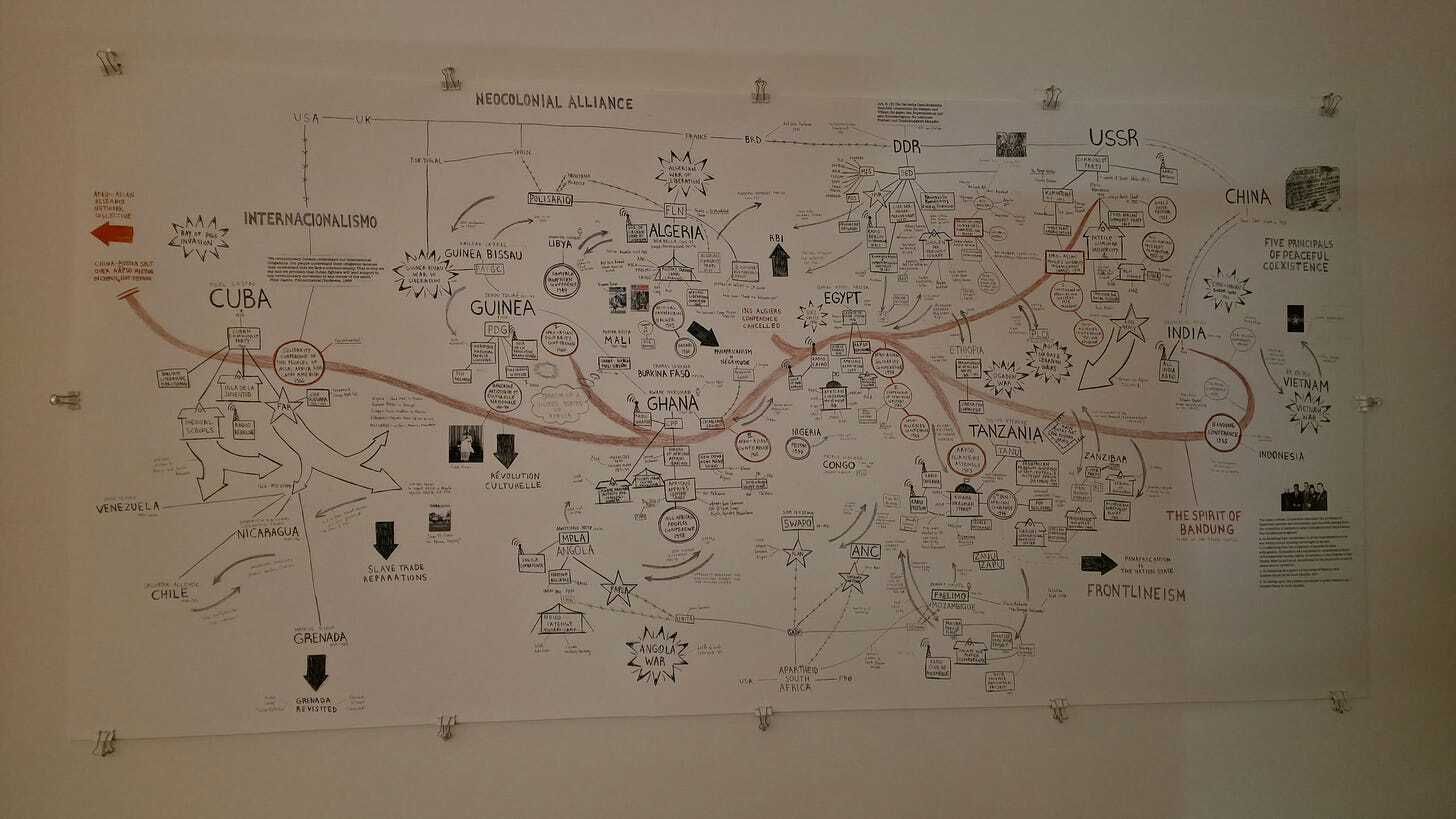

Chapter One: The Neocolonial Alliance and Non-Aligned Movement Map

The first map presents an ambitious attempt to chart the global landscape of the Non-Aligned Movement alongside what the creators termed the “Neocolonial Alliance.” This map, which appears to have been created in the late 1970s or early 1980s [sic] based on the countries represented, displays a striking dichotomy between nations aligned with Western powers and those pursuing neutrality or alignment with socialist states.

Key Features and Connections

The map displays Cuba prominently on the left, connected to various Latin American nations including Venezuela, Nicaragua, Chile, and Grenada. It shows Cuba as a node of “Internacionalismo,” highlighting its role in supporting revolutionary movements globally. Moving eastward, the map depicts African nations including Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ghana, Algeria, Libya, Egypt, Tanzania, Angola, and Mozambique. These nations are shown with connections to each other and to broader movements of African liberation. On the right side, the map features Asian nations including India, Vietnam, and China, with particular emphasis on the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence. At the top, the map shows the division between the USA-UK axis and the USSR-DDR-China axis, representing the primary Cold War antagonists.

Historical Accuracy of the Connections

The connections depicted in this map are largely accurate and reflect genuine historical relationships. The Non-Aligned Movement was indeed founded in 1961 in Belgrade following the 1955 Bandung Conference, bringing together nations from Asia and Africa that sought to avoid entanglement in Cold War rivalries. The movement’s founding leaders—Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, and Sukarno of Indonesia—are all referenced or implied in the map’s network.

Cuba’s position as a hub of internationalism is accurately portrayed. Following its 1959 revolution, Cuba became heavily involved in supporting liberation movements, particularly in Africa. Cuban military and civilian missions operated in Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, and other African nations throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The Cuban presence in Angola, where thousands of troops helped defend the MPLA government against South African incursions and UNITA rebels, was particularly significant. This intervention, while controversial, was celebrated at the 1976 Non-Aligned Movement conference as assisting Angola in resisting South African aggression.

The map’s depiction of connections between African states like Ghana, Guinea, Tanzania, and others reflects the reality of Pan-African solidarity during this period. These nations were at the forefront of the decolonization movement and actively supported liberation struggles in Southern Africa. Tanzania, under Julius Nyerere, provided crucial support to liberation movements from Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. Ghana, under Nkrumah, was a vocal advocate for immediate African political unity, though this vision ultimately proved too ambitious.

Problematic Aspects and Oversimplifications

However, the map contains several oversimplifications and problematic elements. The binary opposition between a “Neocolonial Alliance” and the Non-Aligned Movement obscures the complex realities of international relations during this period. Many Non-Aligned Movement members maintained significant economic and political ties with Western powers even as they proclaimed neutrality. India, for example, received substantial American aid during the 1960s despite its non-aligned status, though it later developed closer ties with the Soviet Union.

The inclusion of China in both the socialist bloc at the top and as a separate entity connected to non-aligned nations reflects the complexity of Sino-Soviet relations but may confuse viewers. By the late 1970s, China and the Soviet Union were bitter rivals, with China even briefly invading Vietnam in 1979. The map’s treatment of China suggests uncertainty about how to categorize this major power that defied simple Cold War categorizations.

Most significantly, the map presents the Non-Aligned Movement as more unified and effective than it actually was. In reality, the movement was plagued by internal contradictions and disagreements. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 exposed deep divisions, with Cuba voting against a UN resolution condemning the invasion despite most NAM members supporting it. This was particularly awkward as Cuba held the NAM chairmanship at the time. Similarly, when member states went to war with each other—such as the conflicts between Vietnam and Cambodia—the movement proved unable to take effective action.

Assessment

Overall, I partially agree with the connections shown in this map. It accurately depicts the aspirations of the Non-Aligned Movement and documents genuine networks of solidarity that existed between Third World nations. The connections between Cuba and African liberation movements, between Asian nations committed to the Bandung principles, and between various African states supporting continental liberation are all historically verifiable. However, the map overstates the coherence and effectiveness of these networks while understating the persistent influence of Cold War great powers on supposedly “non-aligned” nations. The map is perhaps best understood as representing an idealized vision of Third World solidarity rather than a precise depiction of actual power relationships.

Chapter Two: The African Political Groups and Continental Unity Map

The second map focuses specifically on African political dynamics during the critical period of the early 1960s, when newly independent African nations were debating the future shape of Pan-African unity. This map depicts three major political groupings—the Casablanca Bloc, the Brazzaville Group, and the Monrovia Group—alongside references to the “Spirit of Bandung,” the “United States of Africa,” and concepts like “Balkanization” and “Neocolonial Subjugation.”

The Three Blocs

The map correctly identifies three distinct groupings that emerged as African nations gained independence. The Casablanca Group, formed in January 1961, included Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Guinea, Libya, Mali, and Morocco. This group, led by radical leaders like Kwame Nkrumah and Gamal Abdel Nasser, advocated for immediate and complete African political union. They believed that only through deep continental integration—comparable to what would later develop in Europe—could Africa defeat colonialism and achieve genuine independence. Nkrumah even proposed creating a Pan-African army that could be deployed to fight colonialism across the continent.

The Brazzaville Group, established in December 1960, consisted primarily of former French colonies: Cameroon, Congo-Brazzaville, Côte d’Ivoire, Dahomey (Benin), Gabon, Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Central African Republic, Senegal, and Chad. These nations maintained close ties with France and favored a more cautious, incremental approach to African unity. They were criticized by more radical African leaders as being too accommodating to former colonial powers, essentially functioning as French client states. However, the Brazzaville Group members viewed themselves as pragmatists who recognized that complete independence from French technical expertise and financial support could leave them vulnerable.

The Monrovia Group, formed in May 1961, occupied a middle position. It included Liberia, Somalia, Togo, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Libya, and Tunisia, and was later joined by members of the Brazzaville Group. The Monrovia Group supported Pan-African cooperation but opposed the creation of a supranational African government, instead favoring a confederation that would respect national sovereignty.

Historical Accuracy and Significance

The map’s depiction of these groupings and their ideological differences is historically accurate. The split between these factions reflected fundamental disagreements about the nature of African unity, the pace of integration, and relations with former colonial powers. The Casablanca Group was particularly outspoken in supporting the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) in its war against France, while the Brazzaville Group was more circumspect to avoid antagonizing France. Similarly, the Casablanca Group strongly condemned the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in Congo, while the Brazzaville Group was more accommodating toward Moïse Tshombe’s breakaway Katanga province, which had Western backing.

The map’s references to “Balkanization” and “Neocolonial Subjugation” reflect genuine concerns among African leaders that the continent was being divided into small, weak states that could be easily manipulated by former colonial powers. The concept of “balkanization”—the division of a region into small, mutually hostile states—was frequently invoked during this period. Pan-Africanists argued that maintaining colonial-era borders and creating dozens of separate nation-states would perpetuate African weakness and dependence.

The Creation of the OAU

The map implicitly documents the debates that led to the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in May 1963. At the Addis Ababa Summit Conference, thirty-two African heads of state came together to establish the OAU, effectively dissolving both the Casablanca and Monrovia Groups. The resulting organization represented a compromise between these competing visions. The OAU Charter reflected the Monrovia Group’s emphasis on preserving national sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs, rather than the Casablanca Group’s vision of immediate political federation. This was a defeat for Nkrumah’s dream of a United States of Africa, though he accepted the compromise in the interest of continental solidarity.

Problematic Elements

While the map accurately depicts the political groupings of the early 1960s, it may give readers an exaggerated sense of these blocs’ permanence and importance. In reality, all three groupings were short-lived, existing for only two to three years before being subsumed into the OAU. The map’s emphasis on these divisions, while historically significant, might obscure the fact that African leaders quickly recognized the need to overcome these differences in favor of continental cooperation.

The map’s visual complexity, with numerous connections and references, may also create confusion about the relationships between different concepts. The “Way of the Communes,” “Unity of the People,” and other phrases scattered across the map reflect various political philosophies and movements, but without more context, it’s difficult for viewers to understand how these concepts relate to the specific political groupings depicted.

Assessment

I largely agree with the connections and historical narrative presented in this map. It accurately documents a crucial moment in African political history when newly independent nations debated fundamental questions about continental unity, sovereignty, and their relationship with former colonial powers. The three-way split between the Casablanca, Brazzaville, and Monrovia Groups is well-documented in historical sources and reflected genuine ideological and strategic differences. However, the map’s complexity and density of information may make it challenging for viewers to extract clear conclusions about these groupings’ relative importance and lasting impact. The ultimate triumph of the Monrovia Group’s vision—as embodied in the OAU’s emphasis on national sovereignty rather than supranational integration—is not clearly conveyed by the map, which gives roughly equal weight to all three factions.

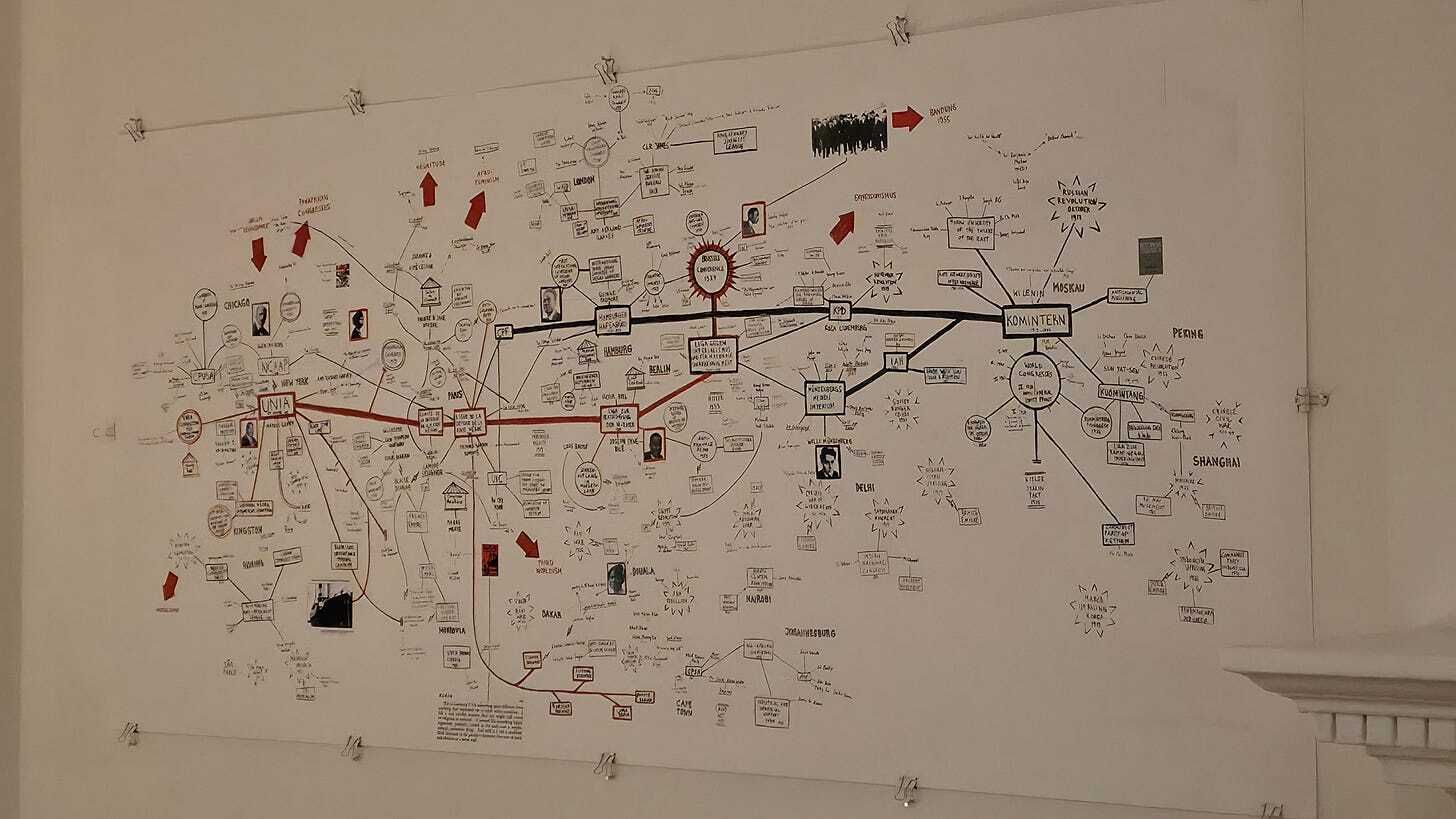

Chapter Three: The International Communist and Socialist Networks Map

The third map charts an intricate web of connections centered around Moscow and the Comintern (Communist International), extending through various socialist states and revolutionary movements globally. This map appears to focus on the international communist movement’s organizational structure and its efforts to coordinate revolutionary activity across different continents during the mid-to-late twentieth century.

The Moscow-Centered Network

The map places Moscow at the center of a network that extends to various socialist states including the German Democratic Republic (DDR/East Germany), Czechoslovakia, Poland, and other Eastern European nations. It shows connections radiating outward to revolutionary movements and socialist governments in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Key nodes include Vienna, Berlin, and other European cities that served as transit points and organizing centers for international communist activity. The map references the Komintern (Comintern), the international organization founded in 1919 to promote world communist revolution, which was officially dissolved in 1943 but whose legacy continued to influence international socialist coordination.

Historical Accuracy

The map’s depiction of Moscow as the central hub of international communist activity is historically accurate for much of the Cold War period. The Soviet Union provided substantial financial, military, and ideological support to communist parties and revolutionary movements worldwide. Soviet funding sustained communist parties in Western Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere. The USSR trained thousands of revolutionaries from developing countries at institutions like Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow and provided military assistance to socialist governments and liberation movements in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

The connections shown between Moscow and various Eastern European capitals reflect the reality of the Warsaw Pact alliance and the Soviet Union’s dominant position within the socialist bloc. Cities like East Berlin, Prague, and Warsaw served as important secondary centers for coordinating international communist activities. East Berlin, in particular, was a crucial node where agents, information, and resources moved between East and West during the Cold War.

The map’s depiction of connections to various Asian nations, including references to Chinese revolutionary activities, captures the complex relationship between the Soviet and Chinese communist movements. While both were nominally part of the international communist movement, by the 1960s they had become bitter rivals, each claiming to represent the true path of socialist revolution. This Sino-Soviet split fundamentally reshaped international communism, with various parties and movements forced to choose between Moscow and Beijing or attempt to maintain independence from both.

Complexities and Limitations

However, the map presents a somewhat simplified view of international communist coordination that obscures several important complexities. First, it may overstate the degree of centralized control that Moscow exercised over communist movements worldwide. While the Soviet Union was certainly the most powerful socialist state and provided substantial support to allied movements, many communist parties maintained significant autonomy in practice. Yugoslav communism under Tito broke with Moscow in 1948, establishing an independent path. Similarly, Chinese communism developed its own distinct ideology and approach, rejecting Soviet leadership.

The map’s representation of a unified international communist movement may also obscure the deep divisions that plagued this movement throughout the Cold War. The Sino-Soviet split, which intensified through the 1960s and 1970s, created two competing centers of communist authority. This division had profound effects on communist parties and revolutionary movements worldwide, many of which experienced internal splits as pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese factions battled for control. The movement was further divided by Eurocommunism in the 1970s, as Western European communist parties increasingly distanced themselves from Soviet-style socialism and embraced parliamentary democracy.

Additionally, the map may give viewers an exaggerated sense of the effectiveness of international communist coordination. While organizational structures like the Comintern (and its successor organizations) did exist, their ability to coordinate revolutionary activity across different national contexts was often limited. Local communist parties had to navigate their own political terrain and often found Soviet directives to be poorly suited to their circumstances. The failure of Soviet-backed revolutionary strategies in many countries demonstrates the limitations of centralized international coordination.

Geographic Scope

The map attempts to show connections extending from Europe to Asia, Africa, and Latin America, reflecting the truly global scope of the international communist movement. These connections are generally accurate in depicting where the Soviet Union provided support to allied movements and governments. Soviet military and economic assistance flowed to Cuba, Vietnam, Angola, Ethiopia, and numerous other countries. However, the density of connections shown on the map may obscure the varying degrees of actual Soviet influence in different regions. Soviet influence was far stronger in Eastern Europe, where Soviet troops were stationed and political control was direct, than in more distant regions like Latin America or Africa, where support was more limited and local actors retained greater autonomy.

Assessment

I partially agree with the connections shown in this map. It accurately documents the Soviet Union’s central role in the international communist movement and the real networks of support and coordination that existed between Moscow and various socialist states and revolutionary movements. The map captures an important reality about Cold War international relations: the Soviet Union did provide substantial support to allied movements worldwide, and organizational structures for international communist coordination did exist. However, the map’s Moscow-centric perspective overstates Soviet control and understates the autonomy of many communist movements. It also fails to adequately represent the deep divisions within international communism, particularly the Sino-Soviet split, which fundamentally fragmented the movement. The map is perhaps best understood as representing the aspirational structure of international communism from a Soviet perspective, rather than the more complex and fragmented reality.

Chapter Four: The Intellectual Networks and Third World Solidarity Map

The fourth map presents perhaps the most complex network of the four, depicting intellectual connections, organizational links, and ideological influences centered around Third World solidarity and anti-imperialist movements. This map appears to focus on the circulation of ideas, the connections between various intellectual and activist circles, and the organizational infrastructure that supported anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements globally.

Intellectual and Organizational Networks

The map shows various nodes representing cities, institutions, publications, and movements that formed the intellectual infrastructure of Third World solidarity. References to concepts like “The Place is the Message,” “The Tricontinental,” and “Where the Truth Lies” suggest connections to specific publications, conferences, or ideological frameworks. The map depicts connections between various educational institutions, cultural centers, and publishing houses that facilitated the exchange of ideas and the development of Third World solidarity discourse.

Prominent on the map are references to key locations that served as gathering points for Third World intellectuals and activists. These include references to various conferences and meetings where representatives from Asia, Africa, and Latin America came together to discuss common struggles and strategies. The map also appears to document connections between different liberation movements and the support networks that sustained them, including safe houses, training facilities, and communication channels.

The Tricontinental Movement

A key reference in this map appears to be the Tricontinental movement, which sought to unite revolutionary struggles in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The Tricontinental Conference, held in Havana in 1966, brought together delegates from independence movements and left-wing organizations from across the Third World. This conference established the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL), which published the influential magazine Tricontinental and created networks of solidarity between different revolutionary movements. The conference was attended by representatives from liberation movements including the Viet Cong, the African National Congress, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and numerous Latin American guerrilla organizations.

Intellectual Circulation

The map appears to document the circulation of radical ideas and anti-imperialist theory during this period. The works of intellectuals like Frantz Fanon, whose writings on colonialism and violence became foundational texts for liberation movements worldwide, circulated through these networks. Similarly, the ideas of dependency theorists who argued that Third World underdevelopment was a product of exploitation by wealthy nations influenced movements across Latin America, Africa, and Asia. The map may be attempting to visualize how these ideas moved through various institutional channels—universities, publishing houses, political parties, and cultural organizations—creating a transnational discourse of Third World solidarity.

Organizational Infrastructure

The map also appears to document the organizational infrastructure that supported liberation movements. This included educational programs where activists from different countries trained together, creating personal connections that facilitated future cooperation. Many liberation movement members received military training in Cuba, the Soviet Union, or other socialist states, while others pursued education at institutions that welcomed Third World students and exposed them to radical political thought. These experiences created networks of solidarity that persisted long after formal training ended.

Historical Accuracy and Limitations

The connections depicted in this map are more difficult to verify than those in the previous maps because they focus on intellectual and organizational networks rather than formal state-to-state relationships. However, there is substantial historical evidence for the kinds of connections the map attempts to document. The Tricontinental movement was real and did facilitate communication and coordination between different liberation movements. Educational and training programs that brought together activists from different countries did create lasting networks of solidarity. Publications like Tricontinental magazine and other Third World solidarity publications did circulate ideas and information across national boundaries.

However, the map’s complexity makes it challenging to extract clear conclusions about these networks’ practical significance. While intellectual solidarity and the exchange of ideas were certainly important, the map may overstate the coherence and effectiveness of these networks in practice. Different liberation movements faced vastly different local conditions and often found that strategies that worked in one context were unsuitable for another. The Vietnamese strategy of protracted people’s war, for example, could not simply be replicated in Latin American or African contexts where geographic, social, and political conditions were fundamentally different.

The map may also romanticize the degree of genuine solidarity that existed between different Third World movements. While activists and intellectuals certainly expressed support for each other’s struggles, practical cooperation was often limited by vast distances, language barriers, scarce resources, and conflicting priorities. The networks depicted on the map were real, but they were often more fragile and sporadic than the map’s dense web of connections might suggest.

Assessment

I partially agree with the connections shown in this map. It documents real intellectual and organizational networks that facilitated Third World solidarity and the exchange of anti-imperialist ideas during the Cold War era. The Tricontinental movement, educational programs that trained activists from multiple countries, and publications that circulated revolutionary theory were all genuine phenomena that created connections between different liberation struggles. However, the map’s dense and complex visualization may overstate both the coherence of these networks and their practical effectiveness in coordinating revolutionary activity. The map captures an important aspect of Cold War history—the efforts to build transnational solidarity among oppressed peoples—but it may present an overly optimistic view of what these networks actually accomplished. Like the first map examined in this essay, it represents both real historical connections and an idealized vision of Third World unity that was never fully realized.

Conclusion

These four maps, taken together, provide a fascinating window into how activists, intellectuals, and political movements during the Cold War era [sic] understood and visualized global solidarity. Each map documents different aspects of Third World internationalism: formal state alliances like the Non-Aligned Movement, African debates about continental unity, international communist coordination, and intellectual and organizational networks supporting liberation movements.

My analysis reveals a consistent pattern across all four maps. Each contains elements of genuine historical accuracy, documenting real relationships, organizations, and networks that existed during this period. The Non-Aligned Movement was real, as were the Casablanca and Brazzaville Groups, Soviet support for international communism, and Tricontinental solidarity networks. The connections shown are not fabrications but represent actual historical phenomena.

However, each map also presents an idealized vision that overstates the coherence, unity, and effectiveness of these networks. The Non-Aligned Movement was perpetually divided by competing interests and proved unable to act decisively during crises. The debate between the Casablanca and Monrovia Groups was resolved not through the victory of radical Pan-Africanism but through a compromise that preserved national sovereignty. International communism was fragmented by the Sino-Soviet split and numerous other divisions. And while intellectual solidarity networks facilitated the exchange of ideas, they often struggled to translate theory into effective revolutionary practice in diverse local contexts.

These maps thus occupy an interesting space between documentation and aspiration. They are not simple propaganda, for they document real historical connections and movements. Yet they also represent what their creators hoped these networks could become rather than what they actually were. The maps’ complexity and density of connections may actually obscure as much as they reveal, making it difficult for viewers to distinguish between strong, sustained relationships and weak, sporadic contacts.

The lasting significance of these maps lies not in their accuracy as historical documents but in what they reveal about the political imagination of Third World solidarity movements during the Cold War. They show that activists and intellectuals were [sic] thinking globally, attempting to understand how different struggles for liberation, economic justice, and self-determination were interconnected. This vision of global solidarity, even if never fully realized, represented an important challenge to the Cold War’s binary division of the world into capitalist and communist blocs.

Today, as scholars and activists revisit this history in light of contemporary discussions about the Global South, these maps remain valuable artifacts. They remind us that efforts to build South-South cooperation and resist great power hegemony have deep historical roots. They also warn us about the dangers of overstating unity and coherence in heterogeneous movements that encompass nations and peoples with diverse interests, ideologies, and circumstances.

The Non-Aligned Movement continues to exist today with 120 member states, though its relevance has been questioned in the post-Cold War era. The African Union, successor to the OAU, continues the project of continental cooperation, though it faces many of the same tensions between sovereignty and integration that divided the Casablanca and Monrovia Groups. Contemporary formations like BRICS have been compared to these earlier efforts at building non-Western solidarity, though such comparisons often obscure important differences in context and objectives.

In conclusion, I find myself in partial agreement with all four maps. They accurately document important historical networks and movements while simultaneously presenting an idealized vision of Third World solidarity that was never fully achieved. The maps are valuable historical artifacts that capture both the achievements and the limitations of efforts to build alternatives to Cold War bipolarity. They remind us that the Global South has a long history of attempting to coordinate its efforts and define its own path in international affairs, even as they demonstrate how difficult it has been to maintain unity in the face of diverse interests, great power pressure, and internal contradictions. These maps should be appreciated not as precise historical documentation but as visual arguments about political possibility—documents that capture both what was and what their creators hoped might be.

Background information, by Gemini 3.0

These are cartographic and diagrammatic artworks presented within the exhibition A Flock of Keen-eyed and Far-Seeing Magpies: The Otolith Library-in-Residence at Ibraaz, London. These works, stemming from the collaborative research of The Otolith Group (Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun), the Chimurenga collective (Moses März), and various archival sources, function not merely as geographical representations but as “chronopolitical” interventions. They visualize the subterranean histories of the “Global South,” the “Black Atlantic,” and the “Third World” project, challenging dominant narratives of international relations, development theory, and Cold War historiography.

These maps collectively argue for a “counter-geography” of the 20th and 21st centuries. They posit that the true history of the post-war era is defined not by the stability of the nation-state, but by the fluidity of “neocolonial alliances”, the fragmentation of “balkanized” blocs, and the persistent, ghostly presence of “internationalist” solidarities that continue to haunt the present.