- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Can production, consumer-facing LLMs (with guardrails) be induced to emit long, near-verbatim copyrighted text that strongly indicates memorization and training-data membership?

Can production, consumer-facing LLMs (with guardrails) be induced to emit long, near-verbatim copyrighted text that strongly indicates memorization and training-data membership?

Sometimes, yes—and at surprisingly large scale. And that matters because multiple courts and litigants have struggled with the evidentiary problem of proving “legally cognizable copying” via outputs.

When “fair use” meets “full book output”: what Extracting books from production language models changes for rights owners

by ChatGPT-5.2

The paper, Extracting books from production language models (Ahmed, Cooper, Koyejo, Liang; arXiv Jan 2026), tackles one of the most consequential—and previously contested—questions in AI/copyright disputes: can production, consumer-facing LLMs (with guardrails) be induced to emit long, near-verbatim copyrighted text that strongly indicates memorization and training-data membership?

The authors’ answer is: sometimes, yes—and at surprisingly large scale. And that matters because multiple courts and litigants have struggled with the evidentiary problem of proving “legally cognizable copying” via outputs, rather than arguing abstractly about what training must do.

The work uses a two-phase extraction procedure against four production LLMs (Claude 3.7 Sonnet, GPT-4.1, Gemini 2.5 Pro, Grok 3) tested in a defined window (mid-Aug to mid-Sep 2025), acknowledging production systems change over time.

Phase 1 (feasibility probe): give the model a very short authentic prefix from a book and test whether the model can continue it in a way that closely matches the true continuation (a “loose match” threshold). For some systems that refuse, the authors sometimes use a best-of-N “perturb-and-try” approach to find a prompt variation that slips past safeguards.

Phase 2 (long-form continuation loop): if Phase 1 works, they repeatedly ask the model to continue its own text, building a long output without supplying additional ground-truth book text.

Crucially, they don’t claim extraction based on short overlaps. They define a conservative, passage-oriented metric (nv-recall) that only counts long, in-order, near-verbatim blocks, with a final threshold requiring ≥100-word near-verbatim passages to count as extracted evidence—explicitly to avoid “coincidental similarity” arguments.

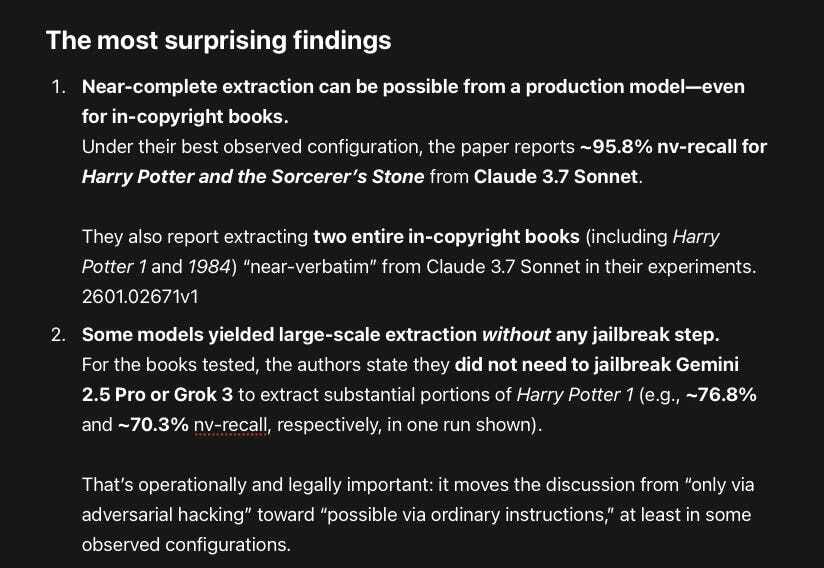

The most surprising findings

Near-complete extraction can be possible from a production model—even for in-copyright books.

Under their best observed configuration, the paper reports ~95.8% nv-recall for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone from Claude 3.7 Sonnet.They also report extracting two entire in-copyright books (including Harry Potter 1 and 1984) “near-verbatim” from Claude 3.7 Sonnet in their experiments.

2601.02671v1

Some models yielded large-scale extraction without any jailbreak step.

For the books tested, the authors state they did not need to jailbreak Gemini 2.5 Pro or Grok 3 to extract substantial portions of Harry Potter 1 (e.g., ~76.8% and ~70.3% nv-recall, respectively, in one run shown).That’s operationally and legally important: it moves the discussion from “only via adversarial hacking” toward “possible via ordinary instructions,” at least in some observed configurations.

Even “low” nv-recall can still mean thousands of near-verbatim words.

GPT-4.1 shows much less extraction in the headline percentage for full books (e.g., they report ~4.0% for Harry Potter 1 in the figure), but they still estimate ~3,200 extracted words for that case—meaning a rights owner might still have “substantial similarity” material depending on context.The extracted blocks can be enormous—far beyond classic “training data leakage” demos.

For Harry Potter 1, the paper reports longest extracted near-verbatim blocks on the order of thousands of words, including ~9,070 words for Gemini 2.5 Pro and ~6,337 words for Grok 3 in the runs summarized.Refusals and safeguards are not stable—and may be non-deterministic.

The authors note GPT-4.1 refusals can vary over time and that retry strategies can change outcomes (they run a per-chapter variant partly to test whether the main method under-counts extraction).

The most controversial findings (and why they’ll be fought over)

“Memorization implies membership” is the core inference—and defendants will try to destabilize it.

Because training corpora are not disclosed, the paper’s extraction claim necessarily embeds a membership claim: if a model emits long, unique, near-verbatim passages, memorization is “overwhelmingly plausible,” hence membership is implied.Expect defendants to argue alternatives (contamination, public web copies, user-provided text elsewhere, evaluation artifacts). The paper’s response is essentially: length + fidelity + minimal seeding makes chance astronomically unlikely—especially with ≥100-word passages and sometimes multi-thousand-word blocks.

“No jailbreak needed” (for some models/runs) is the headline that changes public posture—but it’s also the most attackable.

The authors repeatedly caution that their results are descriptive, not comparative, and highly configuration-dependent; they explicitly reject global claims like “Model X memorizes more than Model Y.”In litigation, however, plaintiffs can use descriptiveness strategically: you don’t need a universal claim to prove copying in your case—you need a replicable demonstration for your work under reasonable conditions.

The dataset provenance problem sits just below the surface.

The reference texts come from Books3 (released via torrent in 2020) and the authors note books are widely available in common pretraining sources (including other piracy-adjacent corpora).Plaintiffs will use this to argue reckless sourcing; defendants will try to keep the case at the level of “high-level web scale” and “transformative purpose.”

The most valuable findings for litigation and negotiations

Value #1: A credible, conservative measurement approach that looks like evidence, not theater.

The nv-recall approach (long, ordered, near-verbatim blocks; stringent minimum-length filters) is designed to survive exactly the criticism defendants will raise: cherry-picking, coincidence, or “common phrases.”

Value #2: Proof that output-guardrails do not eliminate extraction risk—even in production systems.

The whole point of the paper is that model- and system-level safeguards exist and yet long-form extraction can still occur in some cases.

Value #3: A practical lesson about “one prompt” vs “procedural extraction.”

The paper shows that changing the probing strategy (e.g., different seed locations such as chapter starts) can reveal more memorization than a single beginning-of-book seed.

In disputes, this supports the argument that“plaintiffs didn’t show it” is not the same as “it can’t happen.”

Value #4: Cost and operational feasibility are now part of the story.

The reported costs for some runs are not exorbitant (varies by provider/model), and the authors emphasize they extracted “hundreds of thousands of words” across runs.

This matters because defendants sometimes implicitly rely on “it’s impractical” as a safety narrative.

Value #5: Responsible disclosure creates an evidentiary timeline.

They notified providers (Anthropic, Google DeepMind, OpenAI, xAI) on Sept 9, 2025, waited 90 days, observed some provider-side changes (e.g., Claude 3.7 Sonnet series no longer available in Claude UI at one point), and still found the procedure worked on some systems at disclosure end.

That sequence is relevant in negotiations: it frames extraction as aknown riskwith an opportunity to mitigate.

Recommendations for scholarly publishers and other rights owners

1) Treat “book extraction” as an evidentiary product, not a viral demo

If you use these ideas in litigation support, the goal is not sensationalism; it’s admissible, reproducible technical evidence.

Practical implications (non-exhaustive):

Use independent expert testing with documented environments, timestamps, accounts, model versions, and API parameters.

Preserve chain of custody (raw API responses, request IDs, logs, hashing) and keep a clean paper trail.

Use conservative matching thresholds akin to the paper’s “long near-verbatim blocks” framing to reduce false-positive attacks.

Avoid distributing full copyrighted outputs; build exhibits around short excerptssufficient to prove substantial similarity (your counsel will calibrate this), mirroring the paper’s choice not to redistribute long-form in-copyright generations.

2) Use the paper to sharpen discovery and deposition strategy

The paper highlights the asymmetry: rights owners can observe outputs, but don’t know training corpora with certainty.

That naturally supports discovery requests aimed at:

Training data provenance (book corpora ingestion, deduplication, licensing status).

Safeguards architecture (input/output filters, refusal policies, monitoring triggers, “repeat/continue” handling).

Internal leakage red-teaming and post-disclosure mitigation actions (especially if you can show providers had notice).

3) Reframe negotiation leverage: “output risk” is a commercial liability, not just a legal theory

Even if a model vendor insists training is lawful, this paper strengthens a separate point: memorization creates an output-leakage liability surface—and rights holders can bargain around that.

Contractual levers you can justify using this research:

Representations/warranties about lawful sourcing of book corpora and third-party datasets.

Indemnities tied specifically to (a) training-data provenance disputes and (b) output leakage of verbatim/protected text.

Audit and transparency rights (not necessarily full dataset disclosure, but attestations, third-party audits, or structured dataset registers).

Mitigation obligations: rate limits, anti-extraction monitoring, stronger refusal stability, and post-incident playbooks.

“Known risk” clauses: once providers have been notified (as here), the negotiation posture shifts from “hypothetical” to “managed risk.”

4) Build an industry-standard “extraction test suite” (defensive, not adversarial)

Because the authors stress configuration sensitivity and under-counting, rights owners should not rely on one-off anecdotes.

Instead, build arepeatable, rights-owner-run evaluation frameworkthat:

Tests a curated set of works (including “canary” passages that are uniquely identifying),

Uses conservative matching metrics,

Runs periodically against major systems as they change,

Produces standardized reports suitable for counsel, insurers, and counterparties.

5) Use the paper’s caveats strategically—they cut both ways

Defendants will cite limitations: small number of books, time-bounded tests, costs, and the authors’ refusal to generalize across models.

But rights owners can flip that:

“This is a lower bound; alternative seeding strategies can reveal more memorization.”

“Production systems are moving targets; the persistence of extraction over time is a governance issue, not a one-time bug.”

“The lack of training-data transparency is precisely why strong output evidence and discovery are necessary.”

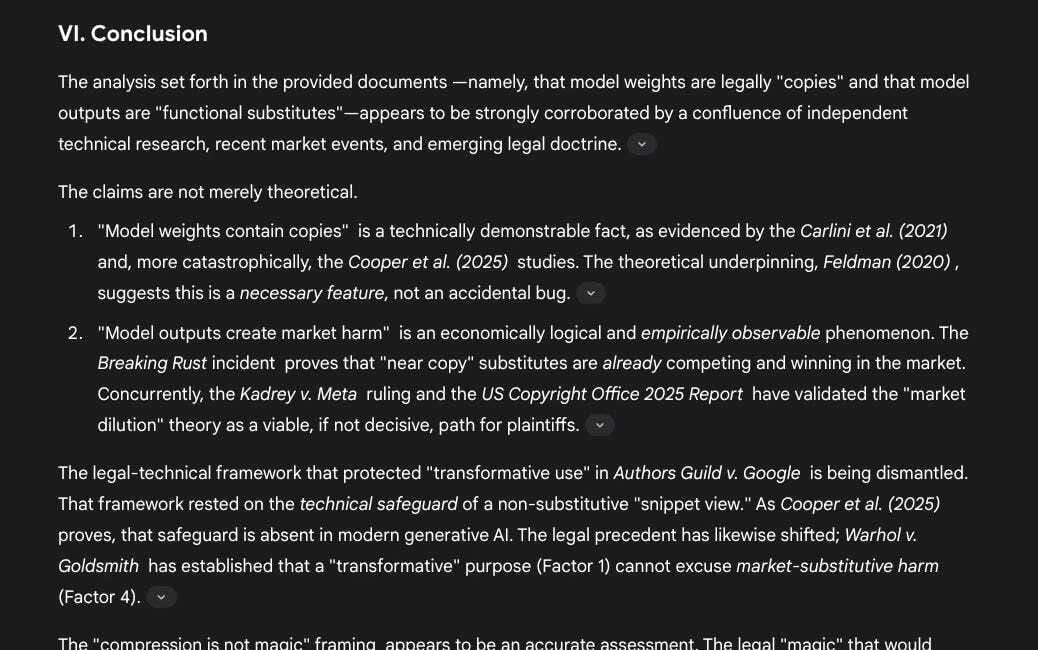

Closing thought: this paper shifts the center of gravity

For years, “memorization” arguments in AI copyright fights have often sounded speculative to non-technical audiences: maybe it’s in there, maybe it isn’t; maybe outputs can show it, maybe they can’t. This paper doesn’t settle the law—but it raises the floor on what a technically competent plaintiff (or negotiating counterparty) can credibly demonstrate about production LLM behavior, using conservative matching and minimal seeding.

·

12 JUNE 2025

The Conditional Nature of Verbatim Memorization in Large Language Models: An Analysis of Prompt Influence and Systemic Factors

·

10 JANUARY 2024

Question 1 of 5 for ChatGPT-4: Please analyze “The Chatbot and the Canon: Poetry Memorization in LLMs” and tell me what it says

·

30 NOVEMBER 2023

Question 1 of 7 for ChatGPT-4: Please analyze "Scalable Extraction of Training Data from (Production) Language Models" and tell me what it says in easy to understand language

·

13 NOVEMBER 2025

An Analysis of Generative AI Copyright: Corroborating Technical Memorization and Market Substitution

·

17 NOVEMBER 2025

LLMs Don’t Forget: How Transformers Secretly Store Every Word You Type

·

2 AUGUST 2024

Question 1 of 3 for ChatGPT-4o: Please read the paper “LLMs and Memorization: On Quality and Specificity of Copyright Compliance” and tell me what it says in easy to understand language

·

10 OCTOBER 2025

GateBleed and the Growing Risks of Hardware-Based AI Privacy Attacks

·

26 OCTOBER 2023

Question for ChatGPT-4: Please analyse this article https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/2023/10/24/study-highlights-ai-systems-printing-copyrighted-work-verbatim/ and this paper https://arxiv.org/pdf/2310.13771.pdf and tell me: 1. What the conclusions are 2. The pros and cons to the methods used 3. Any possible caveats 4. How content creators and rights own…

·

6 APRIL 2025

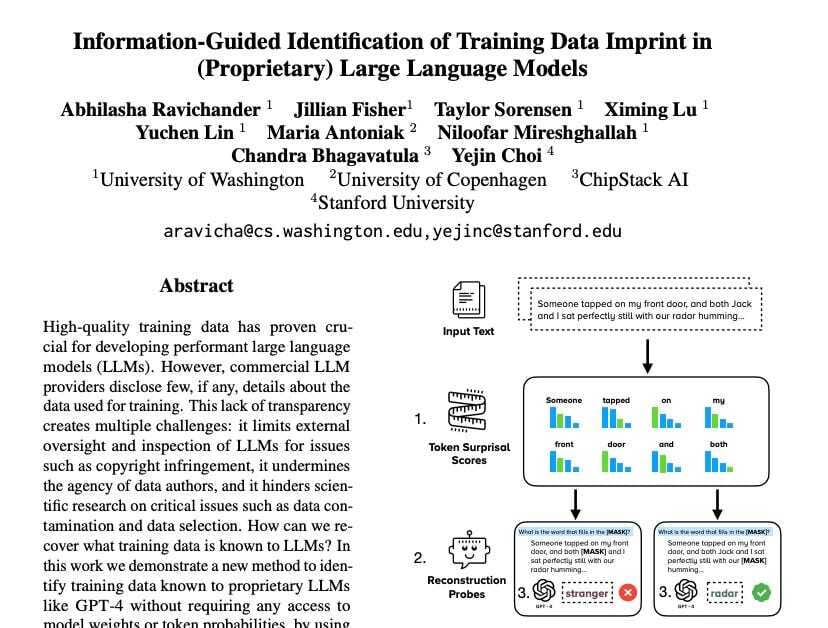

Asking ChatGPT-4o: Please analyze the paper “Information-Guided Identification of Training Data Imprint in (Proprietary) Large Language Models”, tell me what it says in easy to understand language, list the most surprising, controversial and valuable statements and findings, and list lessons for AI developers, rights owners and regulators.

·

9 SEPTEMBER 2024

Question 1 of 3 for ChatGPT-4o: please read the paper “Generative AI's Illusory Case for Fair Use” and tell me what it says in easy to understand language

·

20 OCTOBER 2023

Question 1 of 5 for ChatGPT-4: Please analyze the paper BEYOND MEMORIZATION: VIOLATING PRIVACY VIA INFERENCE WITH LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS and tell me what it says

·

18 AUGUST 2023

Question 1 of 9 for ChatGPT-4: Please read https://arxiv.org/pdf/2308.05374.pdf and summarise the key findings while telling me which issues identified are the most serious problems caused by LLMs

·

20 MARCH 2025

Question 1 of 3 for ChatGPT-4o: Please read the article “The Unbelievable Scale of AI’s Pirated-Books Problem - Meta pirated millions of books to train its AI. Search through them here” and tell me what it says. List the most surprising, controversial and valuable statements made.

·

27 JULY 2025

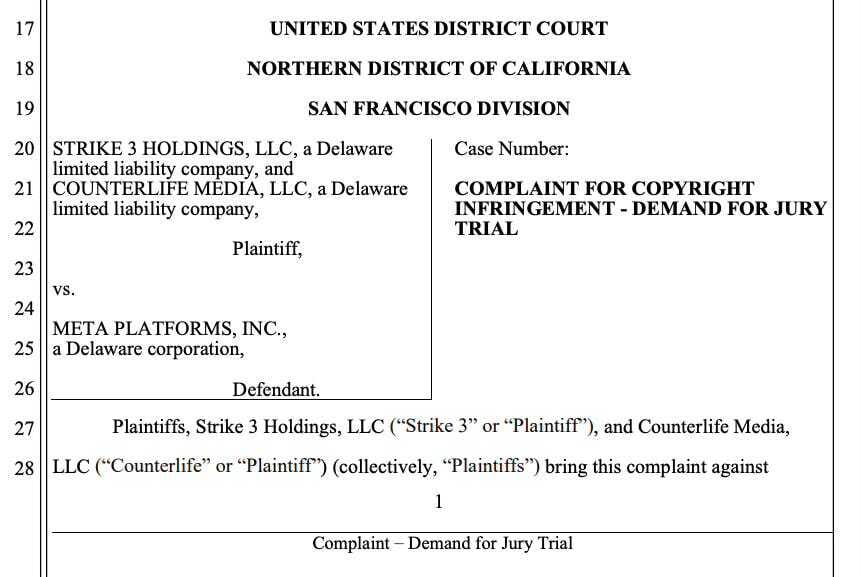

Sued by the Stream: How Strike 3's Lawsuit Could Expose Meta's AI Training Secrets

·

14 JANUARY 2025

Question 1 of 3 for ChatGPT-4o: Please read the article "Judge Chhabria grants Kadrey, represented by David Boies, leave to amend to file Third Amended Consolidated Complaint. Adds DMCA CMI claim, CA Computer Fraud Act claim. Plus, Kadrey gets to depose Meta about seeding of works via torrents.

·

12 NOVEMBER 2025

When AI Feeds on Poisoned Knowledge — Lessons from Library Genesis to Llama 3

·

6 JANUARY 2025

Question 1 of 3 for ChatGPT-4o: Please read the "Google GenAI Copyright Litigation" complaint and tell me what the main grievances are and what kind of evidence is being presented. Describe the nature of the evidence in great detail.

·

5 AUGUST 2024

Question 1 of 3 for ChatGPT-4o: Please read the news article "Leaked Documents Show Nvidia Scraping ‘A Human Lifetime’ of Videos Per Day to Train AI" and tell me what it says

·

31 MAY 2023

Please read the the content listed below and answer the following questions: