- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- By striking a paid licensing deal with Amazon, the NYT demonstrates that its content has quantifiable value in AI development and that using it without permission is not only ethically questionable...

By striking a paid licensing deal with Amazon, the NYT demonstrates that its content has quantifiable value in AI development and that using it without permission is not only ethically questionable...

...but also commercially consequential. The argument that AI makers can’t simply scrape and train on content under the guise of fair use is bolstered by the fact that companies are willing to pay.

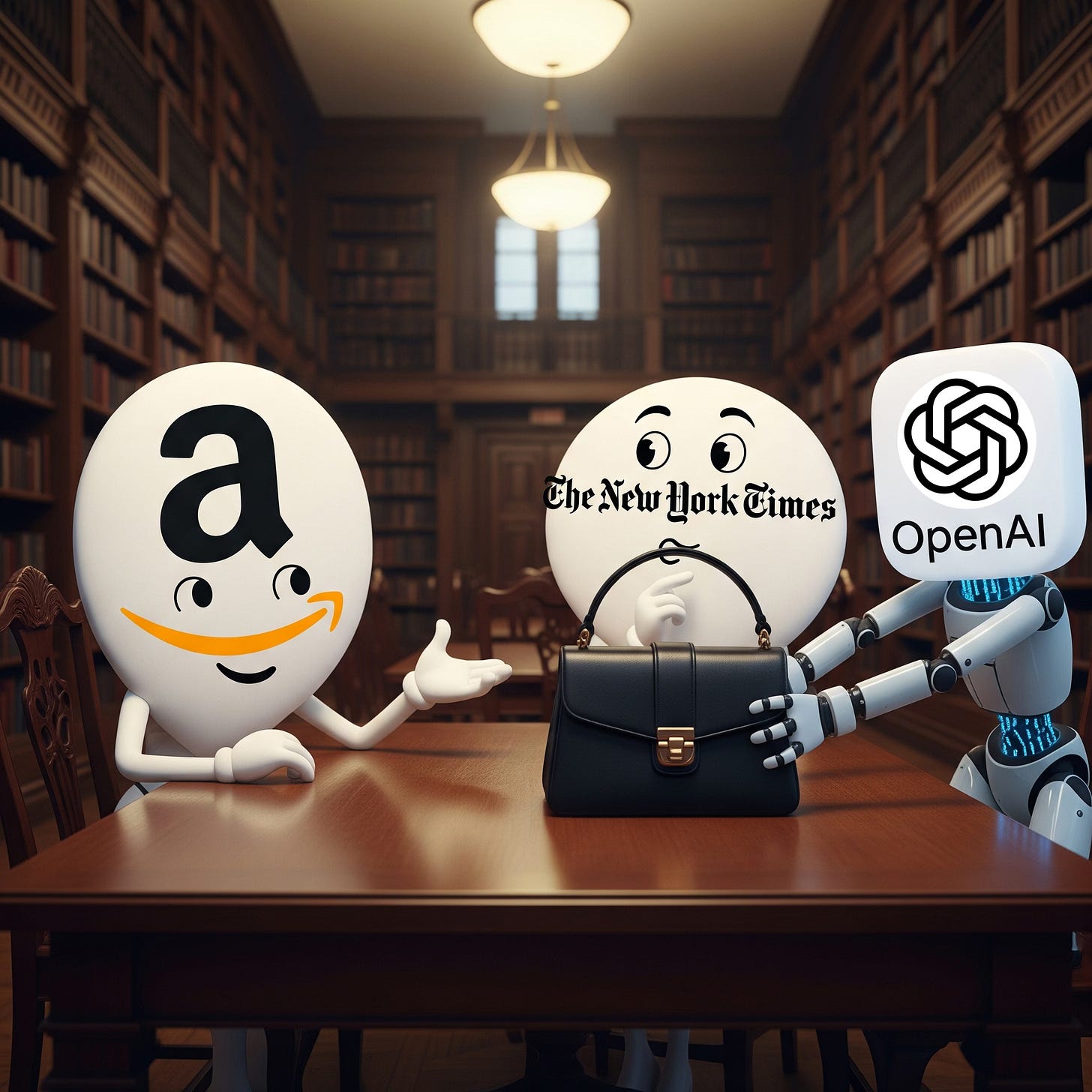

From Litigation to Licensing: The New York Times–Amazon Deal Signals a Turning Point in the AI Copyright Wars

by ChatGPT-4o

The New York Times’ (NYT) licensing deal with Amazon represents a watershed moment in the ongoing clash between content creators and generative AI developers. As the first time the NYT has consented to let its journalism train AI, this deal reverberates across the legal, commercial, and regulatory landscapes.

A. Implications for the Lawsuits Between Rights Owners and AI Makers

This licensing agreement comes amid the NYT’s ongoing lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft, accusing them of “massive copyright infringement” for using millions of NYT articles without authorization. The paradox is glaring: while suing some tech giants for unauthorized training, the NYT is voluntarily licensing its entire archive—including news, recipes, and sports coverage—to Amazon for use in AI products like Alexa and Fire TV.

This move doesn’t undermine the lawsuit—it reinforces its legitimacy. By striking a paid licensing deal with Amazon, the NYT demonstrates that its content has quantifiable value in AI development, and that using it without permission is not only ethically questionable but also commercially consequential. The legal argument that AI makers can’t simply scrape and train on content under the guise of fair use is bolstered by the fact that other companies are willing to pay for that right.

Moreover, it undercuts OpenAI’s defense that training data can be used without permission because it’s publicly accessible. The NYT's agreement with Amazon implies that such content is not freely usable for training without a license, especially when deployed in commercial AI products.

If courts interpret this action as a signal that negotiated licenses are both feasible and preferable, OpenAI and Microsoft may find their fair use claims increasingly tenuous.

B. Should This Motivate AI Makers to Strike More Deals?

Yes, and urgently so. The Amazon-NYT deal illustrates a pragmatic path forward for AI developers: pay to play. It brings several advantages:

Avoid Legal Risk: Licensing reduces exposure to billion-dollar lawsuits and the reputational damage associated with “AI theft.”

Data Quality and Trust: Access to high-quality, curated content like the NYT's archive enhances AI reliability, especially in an era of increasing scrutiny around hallucinations, misinformation, and safety.

Competitive Advantage: Amazon’s move is strategic. With this deal, Amazon narrows the data gap between itself and competitors like OpenAI, which already has arrangements with News Corp and Axel Springer. Owning trusted content pipelines becomes a differentiator in the race for market-ready, enterprise-grade AI.

Signals of Good Faith: By entering into commercial partnerships, AI developers demonstrate ethical commitment to creator rights, potentially influencing regulators and defusing public backlash.

This is not just about avoiding punishment—it’s about accessing better data, building stronger models, and staying ahead of regulatory tightening.

C. Should Regulators Be Incentivising Licensing—Not Enabling AI Theft?

Absolutely. If regulators continue to act as facilitators of Big Tech’s data scraping practices, rather than stewards of a fair digital economy, they risk accelerating:

Market consolidation, where only the AI giants that have already scraped the web dominate innovation.

Democratic erosion, where independent journalism and artistic production collapse under the weight of uncompensated AI replication.

Cultural exploitation, especially of minority voices and underrepresented creators whose work is subsumed without credit or consent.

Regulators should pivot to an approach that incentivizes data licensing through:

Tax credits or subsidies for AI companies that enter into fair data partnerships with creators.

Transparency mandates, requiring AI developers to disclose datasets and document provenance.

Penalties for non-compliance, including fines or exclusion from government contracts for models trained on stolen data.

Support for collective licensing, enabling smaller rights holders to negotiate fair deals through cooperatives or collecting societies.

The current regulatory posture—marked by deference to Big Tech lobbying—risks institutionalizing digital appropriation as the default business model of AI. This not only discourages innovation through collaboration, but also reinforces monopolistic control over knowledge production.

Conclusion

The NYT-Amazon deal is not a contradiction—it is a confrontation. It proves that data licensing is not only viable, but essential for sustainable AI development. It also places legal and moral pressure on other AI makers to stop hiding behind fair use claims and start engaging with the publishers, artists, and educators who power the datasets they exploit.

If regulators remain passive or complicit, they will be remembered not as architects of a just AI economy, but as enablers of one built on digital looting. The time for rules that favor partnership over piracy is now.