- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Both the means of data acquisition (downloading copyrighted works) and the outputs generated by AI models (novel-like continuations or imitations) are valid grounds for litigation—not just...

Both the means of data acquisition (downloading copyrighted works) and the outputs generated by AI models (novel-like continuations or imitations) are valid grounds for litigation—not just...

...abstract issues of transformative use. OpenAI must preserve and potentially produce detailed information. Outputs—even if stemming from fair use training—may still be infringing.

A Turning Point in AI Copyright Litigation—George R.R. Martin, Download Claims, and the Future of Generative AI Accountability

by ChatGPT-4o

Two recent court rulings have sent powerful signals through the growing battleground between authors and AI developers. In the high-profile multidistrict litigation (MDL) against OpenAI and Microsoft, U.S. District Judge Sidney H. Stein ruled that claims by authors, including George R.R. Martin and others, can proceed—marking a watershed moment in the legal landscape around AI training, copyright infringement, and the legitimacy of generative outputs. These developments are not only critical for rights holders but also carry important implications for future litigation strategy, AI model accountability, and the evolving regulatory debate over data use.

Why These Rulings Matter

At the heart of these legal actions is a foundational question: Can an AI system trained on copyrighted works produce outputs so similar to the originals that it constitutes infringement? The George R.R. Martin ruling answers: perhaps yes. Judge Stein cited a ChatGPT-generated sequel titled A Dance With Shadows—featuring Targaryen descendants and ancient dragon magic—as potentially “substantially similar” to Martin’s own work, allowing the copyright claim to move forward.

In tandem, the judge rejected OpenAI’s attempt to strike a related but distinct “book download” claim. OpenAI had argued that the consolidated complaint improperly introduced a new legal theory, but the court disagreed, emphasizing that factual allegations—not legal theories—are what matter in pleading standards. According to the court, the plaintiffs had adequately alleged that OpenAI “captured, downloaded, and copied copyrighted written works” without authorization, regardless of whether the ultimate use was model training.

These decisions affirm that both the means of data acquisition (downloading copyrighted works) and the outputs generated by AI models (novel-like continuations or imitations) are valid grounds for litigation—not just abstract issues of transformative use.

Implications for Rights Holders and Creators

These rulings significantly empower rights holders across content sectors:

Discovery Leverage: OpenAI must preserve and potentially produce detailed logs, Slack messages, and vendor-supplied datasets. This transparency will make it easier for rights holders to connect specific infringements to their works and scrutinize the provenance of training data.

Precedent for Derivative Works: The court’s acknowledgment that AI-generated outputs might be “substantially similar” to copyrighted works bolsters creators’ claims that AI models can replicate—not just remix—protected expression.

Legal Strategy Blueprint: The rulings illustrate how combining allegations of data acquisition (e.g., scraping or downloading) with derivative output examples creates a stronger, multi-pronged case. This could inspire similar suits from musicians, journalists, photographers, and screenwriters.

Fair Use Limits: While other judges (e.g., in Anthropic and Meta cases) have previously ruled in favor of fair use in training contexts, this ruling does not settle that question. Instead, it suggests that outputs—even if stemming from fair use training—may still be infringing.

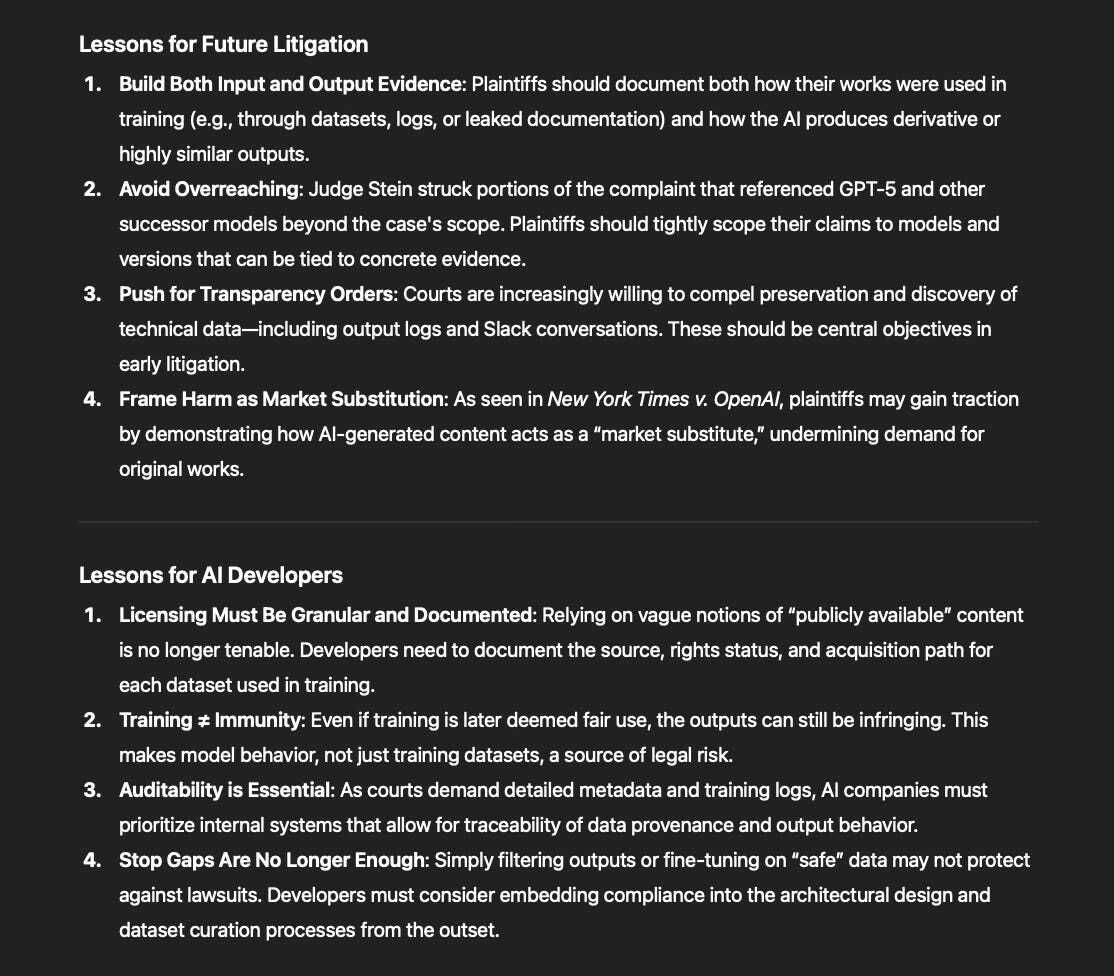

Lessons for Future Litigation

Build Both Input and Output Evidence: Plaintiffs should document both how their works were used in training (e.g., through datasets, logs, or leaked documentation) and how the AI produces derivative or highly similar outputs.

Avoid Overreaching: Judge Stein struck portions of the complaint that referenced GPT-5 and other successor models beyond the case’s scope. Plaintiffs should tightly scope their claims to models and versions that can be tied to concrete evidence.

Push for Transparency Orders: Courts are increasingly willing to compel preservation and discovery of technical data—including output logs and Slack conversations. These should be central objectives in early litigation.

Frame Harm as Market Substitution: As seen in New York Times v. OpenAI, plaintiffs may gain traction by demonstrating how AI-generated content acts as a “market substitute,” undermining demand for original works.

Lessons for AI Developers

Licensing Must Be Granular and Documented: Relying on vague notions of “publicly available” content is no longer tenable. Developers need to document the source, rights status, and acquisition path for each dataset used in training.

Training ≠ Immunity: Even if training is later deemed fair use, the outputs can still be infringing. This makes model behavior, not just training datasets, a source of legal risk.

Auditability is Essential: As courts demand detailed metadata and training logs, AI companies must prioritize internal systems that allow for traceability of data provenance and output behavior.

Stop Gaps Are No Longer Enough: Simply filtering outputs or fine-tuning on “safe” data may not protect against lawsuits. Developers must consider embedding compliance into the architectural design and dataset curation processes from the outset.

Where This Could Lead

These rulings could signal a broader shift toward treating LLMs not as neutral tools but as derivative content machines—especially when trained on copyrighted works. If plaintiffs successfully demonstrate both input misuse and infringing outputs, courts may order data deletion, model untraining, damages, or even licensing mandates—much like they have in music sampling and software piracy cases.

Expect ripple effects beyond books. Visual artists, news organizations, screenwriters, and even educators may begin to build similar dual-track cases. Meanwhile, AI developers may increasingly opt for licensed corpora or open publishing deals to mitigate legal uncertainty, especially in enterprise deployments or consumer-facing apps.

Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call for AI Builders

These rulings represent a critical turning point in defining the legal boundaries of generative AI. They show that courts are willing to scrutinize both the training inputs and the creative outputs of AI models—and that the “black box” defense is crumbling. For AI developers, this is a call to shift from a “scrape now, argue later” model to one of proactive licensing, dataset transparency, and ethical design. For rights holders, it’s a sign that the legal system is starting to catch up with technological disruption—and that the pen may yet be mightier than the algorithm.