- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Australia’s National AI Plan 2025 is one of the most holistic and forward-thinking national AI strategies published to date. It combines massive investment with strong values, pragmatic regulation.

Australia’s National AI Plan 2025 is one of the most holistic and forward-thinking national AI strategies published to date. It combines massive investment with strong values, pragmatic regulation.

Its surprising strengths lie in consumer adoption, infrastructure ambition, and Indigenous data governance.

Australia’s National AI Plan (2025): An Analytical Essay

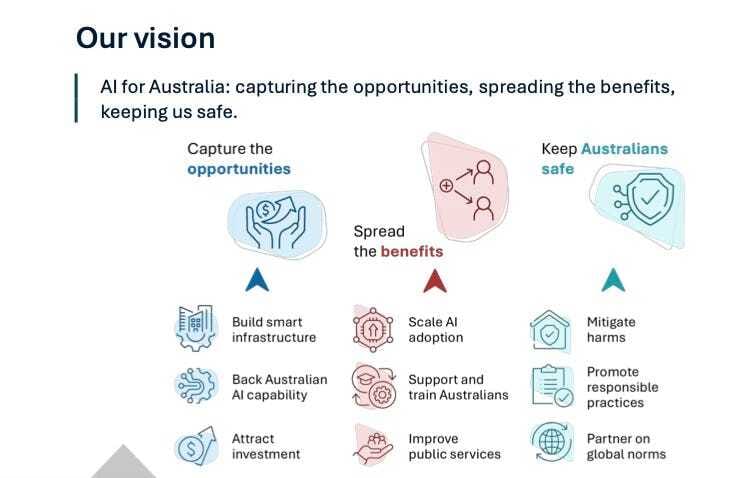

The National AI Plan 2025 outlines one of the most comprehensive and deliberately values-driven AI strategies currently adopted by any middle-power nation. Grounded in three pillars—capturing opportunities, spreading benefits, and keeping Australians safe—the plan blends infrastructure investment, domestic capability-building, workforce protections, and a robust, intentional regulatory philosophy.

Australia aims to position itself as an Indo-Pacific AI hub, a first mover in responsible AI governance, and a country where technological progress is tightly linked to social equity. This essay analyses the plan’s major themes, highlights surprising and controversial features, and evaluates whether Australia’s model should be exported elsewhere.

1. Capturing Opportunities: Infrastructure, Investment & Sovereign Capability

Australia’s approach begins not with tools or rules, but with infrastructure—a recognition that AI competitiveness hinges on compute, connectivity, and trusted data.

The plan highlights extraordinary levels of private investment: more than $100 billion in potential data centre investment announced between 2023–2025, including:

$73.3B expansion by Firmus

$20B by Amazon

$5B by Microsoft

national-ai-plan

The government is simultaneously working on national data centre principles, mapping compute availability, and leveraging Australia’s geographic advantage as an Indo-Pacific conduit through its 15 submarine cables.

Equally important is a commitment to sovereign AI capability, including GovAI—a government-run platform enabling agencies to build and deploy AI solutions domestically and securely. This is one of the more distinct features of Australia’s strategy: it aims not merely to regulate AI companies, but to become a developer and owner of significant AI infrastructure.

2. Spreading the Benefits: An Equitable AI Economy

Australia’s plan is unusually explicit about distributional justice. Its core claim is that AI should reduce inequality, not worsen it. This includes:

Closing the digital divide, with current exclusion affecting 40% of First Nations people and one in five Australians overall.

Addressing the metro–regional divide in AI adoption (40% adoption in metro vs. 29% in regional SME sectors).

Supporting not-for-profits via dedicated “AI Learning Communities.”

Protecting workers, elevating unions as equal partners in AI rollout, and ensuring technology augments rather than replaces labour.

national-ai-plan

In contrast to US or EU strategies, Australia foregrounds labour rights, algorithmic transparency in workplaces, and mandatory consultation with workers before deploying AI-based monitoring or decision systems.

Importantly, workforce transition is framed as task transformation, not job replacement, drawing heavily on Jobs and Skills Australia’s evidence that generative AI reshapes job components rather than eliminating occupations wholesale.

Australia clearly rejects laissez-faire adoption and instead emphasises co-design with affected workers and communities.

3. Keeping Australians Safe: Pragmatic, Risk-Based Regulation

The most distinctive pillar is Australia’s regulatory philosophy:

No sweeping horizontal AI Act (in contrast to the EU).

A reliance on existing laws—consumer, privacy, competition, safety—combined with targeted updates.

A new AI Safety Institute (AISI) modeled partly on the UK but more integrated with regulators.

A firm rejection of a copyright text and data mining exception, preserving rights-holder leverage.

Targeted action against emerging harms: deepfakes, nudify apps, algorithmic bias, AI-enabled crime, misuse of First Nations data, and safety risks.

national-ai-plan

This “layered” approach favours sector-specific guidance, agile rulemaking, and rapid response over sweeping statutory frameworks.

The plan sees safety as “upstream (model-level) and downstream (deployment-level)” and places the AISI at the centre of cross-agency monitoring.

Internationally, Australia positions itself as a responsible middle-power, engaging in the Bletchley Declaration, Hiroshima AI Process, Global Partnership on AI, and a forthcoming US–Australia Technology Prosperity Deal.

Surprising Findings

1. Australia ranks third in global usage of Anthropic’s Claude, adjusted for population.

This demonstrates unusually high consumer AI adoption relative to Australia’s size.

2. Infrastructure investment scale rivals major global tech hubs.

With >$100B in potential data centre investment, Australia becomes the second-largest destination globally in 2024, after the US. This is unexpected for a mid-sized economy.

3. Nearly half of a major data centre provider (CDC) is owned via Australian sovereign funds.

This indicates a deliberate strategy of public–private hybrid sovereignty in critical compute infrastructure.

4. Government aims to potentially use ABS economic datasets for AI training.

This signals a shift toward open, high-value public data as fuel for domestic AI models.

5. Explicit integration of Indigenous data sovereignty principles into AI governance.

Few countries centre Indigenous data rights in technology governance as clearly as Australia.

Controversial Elements

1. Heavy reliance on existing laws instead of dedicated AI legislation.

Critics may argue that “patchwork regulation” is inadequate for frontier AI risks.

2. Strong union involvement in AI deployment.

Global investors may see mandatory consultation obligations as a constraint on rapid innovation.

3. No copyright TDM exception.

This places Australia firmly against US-style fair use approaches and may limit domestic AI model development—but protects rights holders and creators.

4. Ambition to become a regional AI hub via massive data centre growth.

Environmental groups may challenge energy and water usage projections, even with sustainable cooling.

5. Government-led AI development (GovAI)

This raises concerns about:

state power concentration,

procurement favouritism,

risk of bureaucratic inertia slowing innovation.

Most Valuable Contributions

1. A three-pillar model linking opportunity, equity, and safety.

Most countries focus on opportunity vs. safety; Australia embeds inclusion as a third equal pillar.

2. Pragmatic regulatory strategy.

Not as rigid as the EU AI Act, yet more proactive than the US voluntary framework.

3. Whole-of-government integration into public services.

The APS AI Plan requires:

Chief AI Officers in every agency

Training for every public servant

Secure generative AI tools (GovAI)

This is one of the most actionable government AI adoption plans globally.

4. Strong Indo-Pacific strategy.

The plan positions Australia as a trusted regional provider of AI capability and infrastructure, counterbalancing China’s growing influence.

5. Commitment to sustainable AI infrastructure.

Innovations such as near-zero-water cooling and renewable-powered data centres reflect world-leading practice.

Do I Agree With Australia’s Overall Approach?

Yes—strongly.

Australia’s approach strikes an unusually balanced combination of:

Economic competitiveness (massive infrastructure investment)

Sovereignty and resilience (domestic capability, GovAI, public datasets)

Social equity (digital inclusion, worker protections, First Nations principles)

Pragmatic regulation (sector-specific, agile, safety-first)

International leadership (regional norms-setting)

It avoids the regulatory overreach of the EU, the laissez-faire fragmentation of the US, and the authoritarian centralisation of China.

Still, Australia must monitor risk creep: reliance on existing laws may be insufficient as frontier models advance. It will need to deepen regulatory powers and develop testing, auditability, and oversight regimes—possibly through the AISI—especially if AGI-level capabilities emerge.

Should Other Countries Follow This Model?

Countries that should adopt large parts of this model:

Canada, UK, New Zealand: similar governance cultures; strong alignment with risk-based regulation and public service needs.

EU Member States: could benefit from Australia’s pragmatic approach to workforce transition, Indigenous rights, and public service AI deployment.

Middle-power democracies (Japan, South Korea, Singapore): Australia’s Indo-Pacific positioning complements their regional strategies.

Countries that should adopt specific components:

United States:

Worker protection frameworks

Public service AI clarity

Indigenous data sovereignty

Developing nations:

AI literacy hubs

SME-focused adoption programs

Model of linking AI investment to renewable energy requirements

Countries that may struggle to replicate the model:

States with weak democratic institutions may find its worker-centred, rights-based architecture incompatible with existing governance norms.

Overall, the Australian model is exportable, ethically grounded, and globally relevant—especially its balance between innovation and protection, its values orientation, and its strategic investment in infrastructure and public services.

Conclusion

Australia’s National AI Plan 2025 is one of the most holistic and forward-thinking national AI strategies published to date. It combines massive investment with strong values, pragmatic regulation with inclusion, and domestic capability with international leadership.

Its surprising strengths lie in consumer adoption, infrastructure ambition, and Indigenous data governance. Its controversies stem from its labour-centric deployment model, sustainability debates, and strategic choice to avoid a horizontal AI Act.

Nonetheless, Australia offers a blueprint for democratic, middle-power nations seeking a balanced, socially conscious, economically competitive approach to AI governance. Many countries would benefit from adapting its principles, even if local variations are necessary.