- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- At a fundamental cognitive level, we are predisposed to resonate more deeply with the pain of "us" than with the pain of "them." By framing out-groups as dangerous, threatening, or competitive...

At a fundamental cognitive level, we are predisposed to resonate more deeply with the pain of "us" than with the pain of "them." By framing out-groups as dangerous, threatening, or competitive...

...political actors can manipulate these innate cognitive biases, widening the empathy gap and making prejudice, discrimination, and violence seem more psychologically acceptable to the in-group.

This report was inspired by:

@ashleytheebarroness #operationpaperclip #germany #usa #america #americanhistory #ushistory #government #historytok #fyp

Source: TikTok

The Paradox of Progress: An Inquiry into Technological Ambition, Racial Ideology, and Dehumanization in Western History

by Gemini 2.5 Pro, Deep Research. Warning! LLMs may hallucinate!

Introduction

Framing the Central Paradox

Human history is defined by a profound and persistent paradox: the simultaneous capacity for breathtaking acts of creation and unimaginable acts of destruction. Nowhere is this paradox more starkly illustrated than in the recurring confluence of humanity's most aspirational technological endeavors with its most corrosive ideologies of exclusion and racial hierarchy. The drive to transcend terrestrial limits, to unlock the secrets of the atom, or to perfect the human condition through science has often been shadowed by a willingness to categorize, devalue, and eliminate entire populations. This report posits that this is not a mere historical coincidence but a recurring pattern, one rooted in shared logics of mastery, control, and perfection that animate both the scientific quest for progress and the ideological quest for purity. The ambition to build a rocket capable of reaching the Moon and the ambition to build a "master race" are, on a fundamental level, expressions of a desire to re-engineer the world according to a specific, idealized vision. Understanding the nexus where these ambitions meet is critical to comprehending some of the most troubling chapters of the modern era and navigating the ethical challenges of the future.

Operation Paperclip as a Microcosm

This inquiry begins with a powerful and emblematic case study: the secret post-World War II American intelligence program known as Operation Paperclip. In the immediate aftermath of a global conflict fought to defeat Nazi fascism, the United States government actively recruited, protected, and ultimately celebrated key scientific and technical figures from the Third Reich.1 This act of profound moral compromise was justified in the name of a new imperative: gaining a decisive technological and geopolitical advantage over the Soviet Union in the nascent Cold War.2 Operation Paperclip thus serves as a perfect microcosm of the central paradox under investigation. It encapsulates the moment when the pursuit of technological supremacy—in this case, advanced rocketry and weaponry—was deemed so critical that it necessitated the deliberate whitewashing of complicity in war crimes and genocide. The very individuals who had designed weapons of terror for Adolf Hitler, often relying on the brutal exploitation of slave labor, were repurposed as architects of American security and icons of its space exploration program. This precedent reveals a disturbing calculus where morality becomes negotiable in the face of perceived necessity, and where the promise of a technologically superior future is used to sanitize the horrors of the recent past.

Roadmap of the Report

The structure of this report is designed to move from the specific to the general, using the historical record to build a robust explanatory framework. Section I will provide an in-depth analysis of Operation Paperclip, deconstructing its geopolitical justifications, its moral compromises, and the dual legacies of its key figures to establish the report's foundational evidence. Section II will broaden the historical lens, arguing that the Nazi ideology that Paperclip overlooked was not an aberration but the radical culmination of eugenics and scientific racism, pseudoscientific theories that were mainstream in Western thought and had particularly deep roots in the United States. Section III will then critically evaluate and dismiss two scientifically unsupported hypotheses for this pattern of behavior—one based on genetics and empathy, the other on extraterrestrial intervention—demonstrating their function as simplistic, deterministic fallacies. Having cleared away these pseudoscientific explanations, Section IV will present a more robust, scientifically-grounded alternative, drawing on social psychology, neuroscience, and personality theory to construct an interactive model of dehumanization, intergroup conflict, and prejudice. Finally, Section V will synthesize these threads, arguing that a powerful techno-utopian impulse provides the crucial ideological link, serving as a "moral anesthetic" that connects the ambition for technological transcendence with the willingness to engage in social exclusion. The report will conclude by reflecting on the enduring relevance of this pattern in the context of 21st-century technological advancements.

Section I: The Paperclip Precedent: Pragmatism, Power, and the Price of Progress

Operation Paperclip stands as a stark testament to the complex interplay of national ambition, ethical compromise, and the pursuit of technological dominance. To understand the broader historical pattern at the heart of this inquiry, it is essential to first deconstruct this pivotal program, revealing how the logic of geopolitical competition led to the systematic suppression of moral accountability and created a legacy of celebrated achievement built upon a foundation of unpunished crimes.

The Geopolitical Imperative: A Cold War Calculus

The primary and overriding justification for Operation Paperclip was the stark geopolitical reality of the post-World War II landscape. With the defeat of the Axis powers, the wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union rapidly dissolved, giving way to an ideological and military standoff that would define the next half-century: the Cold War.4 In this new context, the advanced technological knowledge possessed by Nazi Germany was seen not as a tainted relic of a defeated enemy, but as a critical strategic asset. U.S. military and intelligence agencies recognized that German research in areas like rocketry, jet propulsion, and chemical and biological warfare was years ahead of their own.5 The driving fear was twofold: that this expertise would be lost, and, more terrifyingly, that it would be acquired by the Soviet Union, tipping the balance of power decisively in their favor.5

This strategic calculus transformed the German scientists from enemies into indispensable assets. The program, initially codenamed "Operation Overcast," was officially established by the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff on July 20, 1945, and later approved for expansion by President Harry S. Truman on September 3, 1946.5 Its explicit goal was to harness German intellectual resources to bolster America's postwar military and industrial capabilities.8 Ultimately, the program brought more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians, along with their families, to the United States between 1945 and 1959.5 The immense value placed on this "intellectual reparation" was staggering; one estimate valued the acquired patents and industrial processes at US$10 billion.5 The argument, which became increasingly persuasive as Cold War tensions mounted, was one of pure pragmatism: the United States needed these minds for its own weapons programs and, at a minimum, had to deny their talents to the Soviets.4 This framing of "national security" as the ultimate good created an environment where other considerations, including justice and morality, were deemed secondary.

The Moral Compromise: Whitewashing a Genocidal Past

The pragmatic imperative of the Cold War directly collided with the stated principles of the Allied cause. President Truman's original directive for the program was clear: it explicitly forbade the recruitment of anyone who had been a member of the Nazi Party or an "active supporter of Nazism or militarism".7 This created a significant obstacle, as many of the most brilliant and sought-after scientists were not merely passive citizens living under the Third Reich; they were documented members of the Nazi Party, the SA, or the SS, and some were deeply complicit in the regime's worst atrocities.4

Faced with this dilemma, officials within the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner to the CIA, made a deliberate choice to subvert the President's order.7 This was not a case of passive oversight but of active, systematic deception. U.S. intelligence officers methodically altered, concealed, and destroyed incriminating evidence from the scientists' official records.1 They expunged references to Nazi affiliations and war crimes, creating sanitized dossiers that would allow these men to pass security screenings and legally enter the United States. The name "Paperclip" itself originated from the practice of attaching a paperclip to the files of these "problematic" scientists whose records had been altered for approval.10 As the introductory transcript starkly puts it, they "literally erased their Nazi past from official records... change[d] files, forge[d] history, stamped the papers clean".1

This moral laundering was not conducted without dissent. Within the U.S. government, some officials, particularly in the State Department, raised serious ethical objections, viewing the recruitment of former enemies as a security risk and a betrayal of American values.8 Outside of government, prominent public figures, including the physicist Albert Einstein and former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, lodged formal protests against the program.8 However, their concerns were ultimately overruled by the powerful utilitarian argument, championed by military leaders and politicians, that the risk of allowing this invaluable knowledge to fall into Soviet hands was far greater than the moral cost of granting asylum to its creators.8 This decision, made in the name of national security, established a precedent that the pursuit of technological advantage could justify the suspension of ethical accountability.

The Architects of Wonder and War: A Dual Legacy

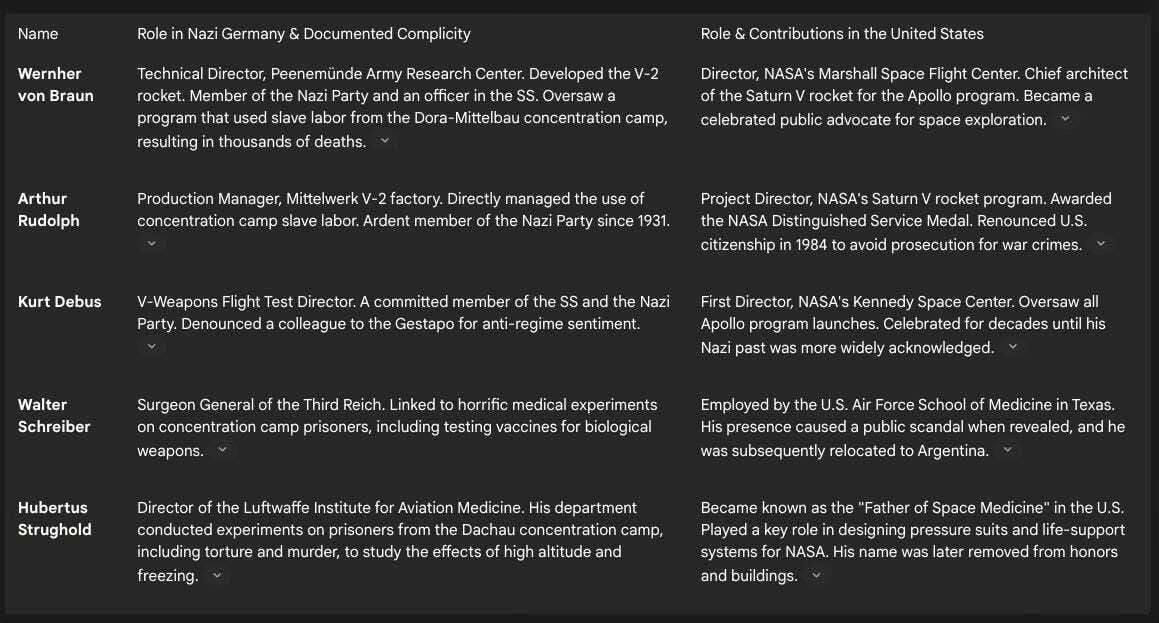

The profound duality of Operation Paperclip is best understood through the lives of its most prominent recruits. These individuals were simultaneously architects of some of humanity's greatest technological achievements and participants in one of its darkest chapters. Their careers embody the central paradox of progress tainted by a criminal past.

Wernher von Braun: Unquestionably the most famous Paperclip scientist, von Braun was the visionary leader of the German V-2 rocket program at Peenemünde.7 This weapon, the world's first long-range ballistic missile, was a tool of terror used to bombard London and Antwerp.12 Crucially, its production relied on the systematic use of slave labor from concentration camps, primarily the subterranean Mittelwerk factory, an extension of the Dora-Mittelbau camp. Thousands of prisoners died from starvation, disease, and execution while building von Braun's rockets.1 Von Braun was not only aware of these conditions but was also a member of the Nazi Party since 1937 and an officer in the SS.11 After surrendering to the Americans, his past was sanitized, and he was transformed into an American hero. He became the director of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and the chief architect of the Saturn V launch vehicle, the colossal rocket that fulfilled President John F. Kennedy's promise of landing a man on the Moon.1 He became the public face of the American dream of space exploration, a dream built on technology he first developed for the Third Reich.

Arthur Rudolph: While von Braun was the visionary, Arthur Rudolph was the operational manager. As the production director at the Mittelwerk factory, he was directly responsible for overseeing the use of concentration camp prisoners in the V-2 program.1 He was a zealous early member of the Nazi Party, joining in 1931.17 In the United States, his managerial expertise was once again put to use. He followed von Braun to NASA and became the project director for the very same Saturn V rocket program.17 For decades, his past remained hidden. However, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, investigations by the Department of Justice's Office of Special Investigations uncovered his role in the use of slave labor. Facing prosecution for war crimes, Rudolph renounced his U.S. citizenship in 1984 and returned to Germany, where he was never tried.2

Kurt Debus: A fervent Nazi and a member of the elite SS, Kurt Debus was the V-weapons flight test director at Peenemünde, overseeing the launch of the V-2 rockets.1 Historical records indicate he was a staunch loyalist who denounced a colleague to the Gestapo for making anti-Nazi remarks.21 In America, his expertise in launch operations made him invaluable. He became NASA's first director of the Launch Operations Center, later renamed the John F. Kennedy Space Center.21 From this position, he presided over more than 150 military and space launches, including the historic Apollo missions that sent humanity to the Moon.20 For decades, he was celebrated as a pioneer, with a conference center and an award named in his honor. It was only in recent years, following increased public scrutiny, that NASA has begun to reckon with his past, renaming the facilities and updating his official biography to include his SS membership.22

These cases are not isolated. They are representative of a pattern of deliberate moral and historical erasure. The table below starkly illustrates the dual legacies of these and other key figures, juxtaposing their roles within the Nazi regime with their celebrated contributions to the United States.

The ease with which American officials were able to rationalize these compromises points to something deeper than simple, amoral pragmatism. The decision to recruit these men was not merely an act of overlooking their pasts; it was, in a sense, an act of recognizing a shared value. The Nazi rocket program was a fusion of immense technological ambition and a profound disregard for the value of certain human lives—those of the slave laborers deemed subhuman. The American Cold War project, while operating under a different political system, also elevated technological dominance to a supreme goal. By recruiting the architects of the former to serve the latter, U.S. officials implicitly endorsed the underlying logic that the grand, transcendent goal of technological progress could legitimize the means used to achieve it. The methodology of dehumanization was different—one was based on racial ideology, the other on geopolitical calculus—but the willingness to treat certain human lives as expendable in service of a grander project revealed a disturbing ideological resonance.

Section II: The Ideological Bedrock: Eugenics, Scientific Racism, and the Pursuit of Purity

The ideology of the Third Reich, which Operation Paperclip so readily excused in the name of progress, was not a historical anomaly that emerged from a vacuum. It was the monstrous and logical culmination of pseudoscientific and racial theories that had been gaining currency throughout the Western world for decades. To fully comprehend the moral blindness of the Paperclip era, one must recognize that its architects were operating within a broader intellectual culture that had long been saturated with its own doctrines of racial hierarchy and biological determinism. The Nazi concept of "racial hygiene" was not an alien import; it was a radicalized expression of ideas that were not only present but mainstream and actively practiced in the United States.

The "Science" of Superiority: The Rise of Eugenics

The intellectual foundation for many 20th-century racial policies was laid in the late 19th century with the rise of eugenics. The term, meaning "good in birth," was coined in 1883 by the English statistician Sir Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin.25 Galton misappropriated his cousin's theories of evolution and applied them to human society, arguing that desirable traits such as intelligence, morality, and social standing were hereditary. He proposed that society could be systematically improved by encouraging the "fittest" individuals to reproduce ("positive eugenics") and, more ominously, by preventing the "unfit" from doing so ("negative eugenics").25

Presented as a modern, rational, and scientific approach to solving complex social problems like poverty, crime, and mental illness, eugenics quickly captured the imagination of intellectuals, social reformers, and political leaders across Europe and North America.26 It promised a technological fix for the perceived biological decay of the population. In the United States, the movement found fertile ground, gaining widespread support and funding from prominent figures and institutions, including the Carnegie Institution, the Rockefeller Foundation, and individuals like cereal magnate John Harvey Kellogg.26 This support led to the establishment of influential organizations like the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor, which served as a clearinghouse for collecting dubious data on human heredity and promoting eugenic policies nationwide.25

From Theory to Practice: American Eugenics Policies

The United States became a global leader in translating eugenic theory into state policy. The American eugenics movement was explicitly racist and classist, targeting those deemed "socially inadequate." This broad and ill-defined category encompassed not only individuals with physical or mental disabilities but also the poor, criminals, and, disproportionately, ethnic and racial minorities.25

The most direct application of eugenic principles was the policy of compulsory sterilization. In 1907, Indiana became the first jurisdiction in the world to pass a compulsory sterilization law.29 Over the next several decades, more than 30 U.S. states followed suit. The legality of these practices was chillingly affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in its 1927 decision,

Buck v. Bell. Writing for the majority, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., upheld a Virginia law allowing for the sterilization of a young woman deemed "feeble-minded," infamously declaring, "Three generations of imbeciles are enough." This ruling provided the legal bedrock for a massive expansion of sterilization programs. Between 1907 and the 1970s, over 60,000 Americans were forcibly sterilized under these laws, with the victims often being poor women and women of color confined to state institutions.25

Eugenics also provided a "scientific" veneer for deeply prejudiced immigration policies. Eugenicists like Madison Grant, in his influential 1916 book The Passing of the Great Race, warned that the influx of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe was diluting America's "superior" Nordic stock.29 This rhetoric directly influenced the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, which established national origin quotas designed to severely restrict immigration from these regions and completely bar immigration from Asia. The explicit goal was to use federal policy to socially engineer the racial and ethnic composition of the nation, preserving what was seen as its Anglo-Saxon character.30

Transatlantic Currents: The American Influence on Nazism

The American eugenics movement did not just run parallel to the Nazi program of "racial hygiene" (Rassenhygiene); it served as a direct inspiration and a practical model.28 German racial theorists in the 1920s and 1930s closely studied and admired American eugenic laws and publications. They saw the United States as a pioneer in applying racial science to public policy.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, they moved quickly to implement their own eugenic agenda. Their "Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring," passed in July 1933, was heavily based on a model sterilization law drafted by the American eugenicist Harry Laughlin, a leader of the Eugenics Record Office.26 This Nazi law would lead to the forced sterilization of an estimated 400,000 Germans deemed "unfit".32 Nazi propaganda often pointed to the extensive sterilization programs in the United States, particularly in California, as proof that such large-scale eugenic measures were both modern and feasible.29 In a disturbing letter, the leader of the German eugenics movement, Ernst Rüdin, praised his American counterparts for their pioneering work, acknowledging the profound influence they had on Nazi thought.

Continue reading here (due to post length constraints): https://p4sc4l.substack.com/p/at-a-fundamental-cognitive-level