- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Allegation: Trump administration has repurposed and fused multiple government databases into a de facto “national citizenship data bank” and is pushing states to use it for mass “voter verification”.

Allegation: Trump administration has repurposed and fused multiple government databases into a de facto “national citizenship data bank” and is pushing states to use it for mass “voter verification”.

When states match voter files against messy, repurposed federal data, U.S. citizens can get flagged as noncitizens and removed from rolls—or forced to jump through paperwork hoops to stay registered

A National “Citizenship Data Bank” Meets Voter Rolls: What the LWV v. DHS Complaint Says—and Why It Matters

by ChatGPT-5.2

The League of Women Voters and EPIC (Electronic Privacy Information Center) filed an amended federal complaint arguing that the Trump administration—through DHS (including USCIS) and the Social Security Administration—has repurposed and fused multiple government databases into a de facto “national citizenship data bank”and is pushing states to use it for mass “voter verification”.

At the center is SAVE (Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements), a system created in 1986 to verify non-citizens’ eligibility for certain benefits—not to run bulk checks on citizens or entire voter rolls. The complaint alleges DHS “overhauled” SAVE in 2025 so states can bulk-upload voter lists and query citizenship using Social Security numbers, drawing heavily on SSA’s NUMIDENT database (the master SSN-holder file).

A WIRED article summarizes the practical fear: when states match voter files against messy, repurposed federal data, U.S. citizens can get flagged as noncitizens and removed from rolls—or forced to jump through paperwork hoops to stay registered.

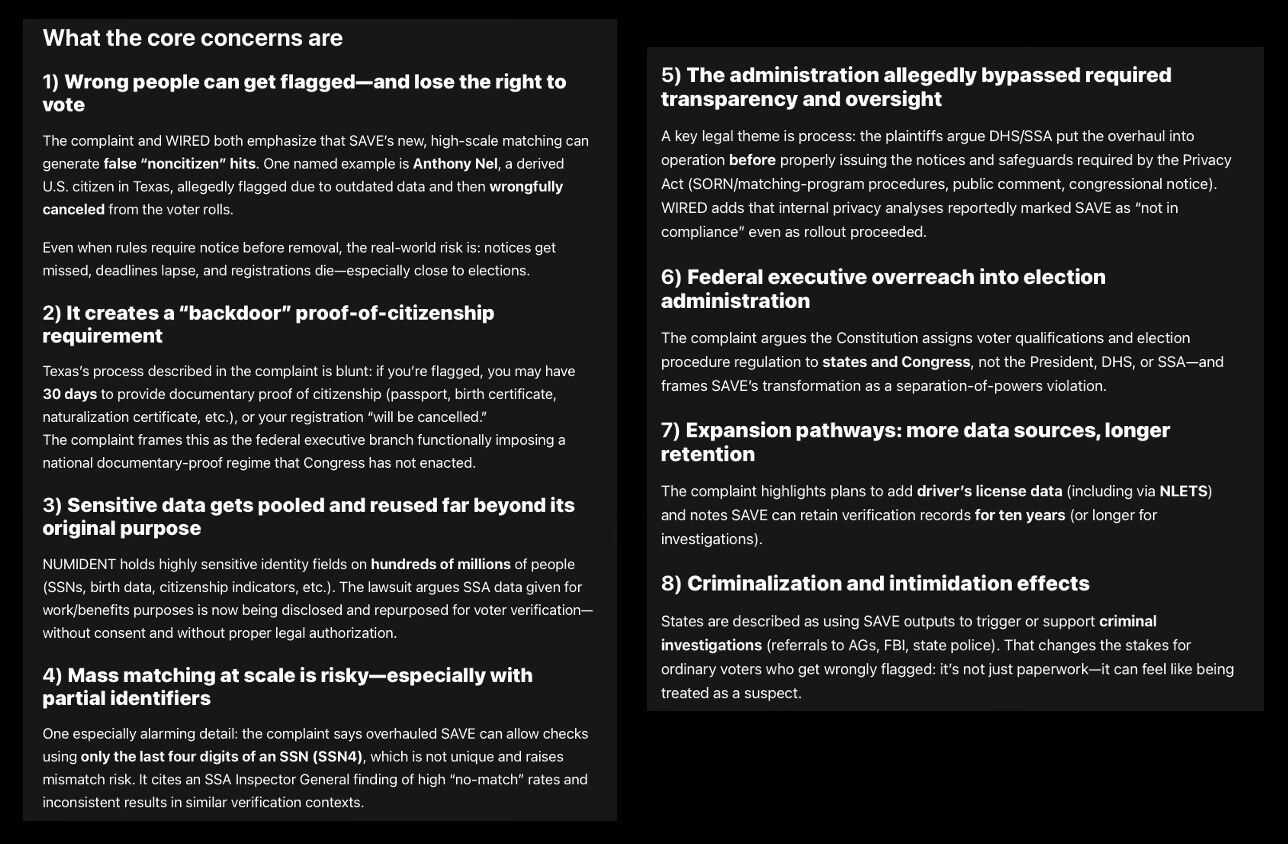

What the core concerns are

1) Wrong people can get flagged—and lose the right to vote

The complaint and WIRED both emphasize that SAVE’s new, high-scale matching can generate false “noncitizen” hits. One named example is Anthony Nel, a derived U.S. citizen in Texas, allegedly flagged due to outdated data and then wrongfully canceled from the voter rolls.

Even when rules require notice before removal, the real-world risk is: notices get missed, deadlines lapse, and registrations die—especially close to elections.

2) It creates a “backdoor” proof-of-citizenship requirement

Texas’s process described in the complaint is blunt: if you’re flagged, you may have 30 days to provide documentary proof of citizenship (passport, birth certificate, naturalization certificate, etc.), or your registration “will be cancelled.”

The complaint frames this as the federal executive branch functionally imposing a national documentary-proof regime that Congress has not enacted.

3) Sensitive data gets pooled and reused far beyond its original purpose

NUMIDENT holds highly sensitive identity fields on hundreds of millions of people (SSNs, birth data, citizenship indicators, etc.). The lawsuit argues SSA data given for work/benefits purposes is now being disclosed and repurposed for voter verification—without consent and without proper legal authorization.

4) Mass matching at scale is risky—especially with partial identifiers

One especially alarming detail: the complaint says overhauled SAVE can allow checks using only the last four digits of an SSN (SSN4), which is not unique and raises mismatch risk. It cites an SSA Inspector General finding of high “no-match” rates and inconsistent results in similar verification contexts.

5) The administration allegedly bypassed required transparency and oversight

A key legal theme is process: the plaintiffs argue DHS/SSA put the overhaul into operation before properly issuing the notices and safeguards required by the Privacy Act (SORN/matching-program procedures, public comment, congressional notice).

WIRED adds that internal privacy analyses reportedly marked SAVE as “not in compliance” even as rollout proceeded.

6) Federal executive overreach into election administration

The complaint argues the Constitution assigns voter qualifications and election procedure regulation to states and Congress, not the President, DHS, or SSA—and frames SAVE’s transformation as a separation-of-powers violation.

7) Expansion pathways: more data sources, longer retention

The complaint highlights plans to add driver’s license data (including via NLETS) and notes SAVE can retain verification records for ten years (or longer for investigations).

8) Criminalization and intimidation effects

States are described as using SAVE outputs to trigger or support criminal investigations (referrals to AGs, FBI, state police). That changes the stakes for ordinary voters who get wrongly flagged: it’s not just paperwork—it can feel like being treated as a suspect.

The most surprising, controversial, and valuable statements/findings in the complaint

Here are the standouts—either because they’re unusually sweeping, unusually specific, or unusually revealing about intent and mechanism:

“Seize control of our nation’s election infrastructure” framing

The opening claim is not cautious—it alleges an executive-branch power grabusing data consolidation to reshape election administration.Scale claims: “46 million voter verification queries”

DHS/USCIS is quoted (via the complaint) claiming SAVE enabled state agencies to submit 46+ million voter verification queries by Nov 3, 2025—an eye-popping number suggesting near-industrialized list processing.Using SSA’s NUMIDENT as a citizenship gatekeeper

The complaint details that SSA returns fields like a “citizenship/foreign indicator” code, death indicator, match flags, etc., which SAVE then uses in automated workflows—despite SSA not being designed as a citizenship verification authority.SSN4 matching

Allowing checks via last four digits is, practically, a recipe for mismatches in large datasets—and the complaint backs it with prior Inspector General warnings.“Not in compliance” internal privacy assessments

The complaint describes DHS PTAs acknowledging the overhaul required modified notices and that continued operation was “not in compliance.” That’s a strong allegation because it implies known legal risk during rollout.Future integration with driver’s license data and NLETS

This is a “scope creep” signal: once the machinery exists, it can expand beyond citizenship checks into broader identity infrastructure.Ten-year retention of verification records

A decade-long retention window (longer for investigations) turns “verification” into an enduring eligibility dossier.A blunt constitutional argument: no direct presidential role

The complaint emphasizes that election infrastructure is not a presidential domain and frames the SAVE overhaul as an executive intrusion into powers reserved to states/Congress.The relief requested is sweeping—delete and “disentangle” pooled data

They don’t just want better guardrails; they ask the court to revert SAVE, and order deletion/unlinking of unlawfully pooled data, including directing user agencies to do the same.

How these alleged measures could help an administration “remain in power” and prevent electoral defeat

I’m going to be careful here: the complaint makes allegations about purpose and effect; the facts would be tested in court. But taking the complaint’s theory seriously, the mechanisms it implies look like this:

A) Disenfranchisement via error-prone purges

If SAVE’s false positives disproportionately hit naturalized/derived citizens or people with complex records, then mass matching plus tight deadlines can reduce turnout among eligible voters—especially those with less time, money, documentation access, or confidence navigating bureaucracy.

B) Chilling effects: turning voting into a risk

When “potential noncitizen” flags lead to referrals for investigation, people may avoid registering, updating addresses, or showing up—because they fear being accused of wrongdoing. Even lawful voters can self-censor if the system feels punitive.

C) Narrative weaponization: “proof” of fraud regardless of accuracy

WIRED quotes concern that simply generating lists of “potential noncitizens” fuels a misinformation ecosystem—even if many flagged entries are citizens. That can prime the public to distrust outcomes and accept extraordinary “integrity” interventions.

D) Pretext for restrictive legislation

A pipeline of “potential noncitizens” can be used to justify statutory proof-of-citizenship rules or broader restrictions. Even if noncitizen voting is rare, lists and headlines become political leverage.

E) Centralizing leverage over states

The complaint’s constitutional point matters strategically: if DHS becomes the de facto national validator states rely on, the executive branch gains structural influenceover voter list maintenance—an area traditionally decentralized.

F) Timing control: disruption close to elections

Mass checks and short cure windows near primaries/general elections can create administrative chaos: voters scramble, local officials get overloaded, errors go uncorrected. Confusion itself becomes a turnout suppressant.

G) Creating a durable eligibility dossier infrastructure

Ten-year retention plus cross-agency linkages can turn a voting “check” into a persistent identity/eligibility profile—useful for future enforcement, targeting, or bureaucratic pressure campaigns.

H) Selective enforcement opportunities

Even if the system is formally neutral, the combination of (1) huge datasets, (2) opaque matching logic, and (3) discretionary follow-up creates room for selective emphasis—where certain jurisdictions or populations experience more scrutiny and friction than others. The complaint implies this risk through its focus on scale, opacity, and lack of mandated transparency.

Countermeasures: what the public, Congress, and Democrats can do

For the public (practical, defensive moves)

Check your registration early and repeatedly, especially if you are naturalized/derived, have changed names, or moved recently.

If you get a notice: treat it like a deadline-driven legal document. Respond fast; keep copies and proof of delivery. (The Texas template described gives 30 days.)

Normalize “documentation readiness” without panic: passport/birth certificate/naturalization documents in one secure place; scanned backup; know how to request replacements.

Support or volunteer with nonpartisan election-protection orgs that can help voters navigate “cure” processes.

For Congress (even with a Republican majority)

These steps can be framed as conservative-friendly governance: accuracy, due process, data security, and federalism.

Oversight hearings + subpoena the PTAs, matching agreements, error metrics, and audit logs (the complaint emphasizes withheld transparency on matching programs).

Appropriations riders: block funding for bulk voter-roll matching unless strict safeguards are met (unique identifier requirements, error-rate thresholds, independent audits, mandatory notice-and-cure standards, ban on SSN4 matching).

Mandate public reporting: false positive rates, demographic impact assessments, and remediation statistics (how many people were flagged, removed, reinstated).

Codify “no-removal based solely on SAVE” without robust secondary verification and due process.

Strengthen Privacy Act enforcement hooks for cross-agency “national data bank” behavior (the complaint’s core claim is that this is what the Privacy Act was designed to prevent).

For Democrats (and aligned state officials)

Litigation + injunction strategy: push fast for preliminary relief where imminent elections are near, using named examples and process violations (notice-and-comment, compatibility/routine use, matching-program requirements, separation of powers).

State-level guardrails (where Democrats govern): prohibit SAVE-only purges; require extended cure periods; require multiple notice channels; allow same-day registration; ensure reinstatement on affidavit pending verification.

Operational countermeasures: surge voter education campaigns in affected states; fund legal clinics; build rapid-response workflows with county registrars.

Legislative messaging discipline: focus on citizens being wrongly removed, data misuse, and federal overreach into state-run elections—themes that can split coalitions and win moderates.

Force transparency: FOIA campaigns + inspector general referrals on SSN use, breach risk, and matching accuracy.

Bottom line

The complaint paints SAVE’s 2025 overhaul as more than a tech upgrade: it’s portrayed as a structural shift toward centralized, executive-branch-controlled eligibility verification, built on repurposed personal data, deployed at scale, and already producing voter harm.

If the allegations are even partly accurate, the biggest democratic danger isn’t just privacy—it’s a feedback loop of bureaucratic friction + fear + false fraud narratives, all of which can reshape who votes and whether the public accepts election outcomes.