- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- Administrative subpoenas can be legitimate tools, but when pointed at lawful dissent they start to resemble a state “unmasking” capability—one that can chill speech without winning a case in court.

Administrative subpoenas can be legitimate tools, but when pointed at lawful dissent they start to resemble a state “unmasking” capability—one that can chill speech without winning a case in court.

For users abroad, the core risk is asymmetry: U.S. process can reach your data through U.S. platforms, while your practical ability to contest or remedy the harm may be limited.

Unmasking Dissent: When Administrative Subpoenas Become a Political Weapon

by ChatGPT-5.2

The TechCrunch reporting describes a pattern in which U.S. Department of Homeland Security (specifically its Homeland Security Investigations unit within U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) has used administrative subpoenas to demand identifying account data from major platforms—seeking to unmask anonymous speakers who document immigration enforcement activity or criticize administration officials. Examples include an attempt to identify the person behind an anonymous Instagram account (@montcowatch) that shared information about local immigration raids, and a separate demand for extensive account data about a private individual after he sent a critical email to a DHS attorney—followed by federal agents visiting his home even though they reportedly conceded he broke no laws.

This is not “content censorship” in the narrow sense (the article notes administrative subpoenas generally can’t compel message content like email bodies or search queries). It’s something often more chilling: identity extraction via metadata—login times, IP addresses, devices, recovery emails, linked payment instruments, and other “non-content” fields that can collapse anonymity and map social networks.

The legal architecture DHS is leaning on

Administrative subpoenas are real, common, and often broad. They exist because Congress has granted certain agencies subpoena power to obtain records relevant to their lawful functions—without first going to a judge. The article points to claimed authority under 8 U.S.C. § 1225(d) and 19 U.S.C. § 1509(a)(1)(immigration/customs-adjacent powers).

Two things can be true at once:

The agency has some statutory subpoena authority (often for immigration, customs, fraud, or enforcement functions).

A particular subpoena can still be unlawful if it’s ultra vires (outside statutory purpose), overbroad, retaliatory, or inconsistent with constitutional limits.

What companies can be compelled to give

As described, administrative subpoenas commonly target subscriber and transactional data (sometimes called “metadata”): identifiers, session logs, IP addresses, device identifiers, account recovery data, etc.

But U.S. law draws important lines:

Content vs. non-content: Many statutes treat message content as more protected than non-content records.

Stored Communications Act / ECPA constraints (conceptually): Even where an agency has administrative subpoena power, other federal privacy statutes may still require a warrant or court order for certain categories of data, especially content-like material or more sensitive records, depending on what exactly is sought and how it’s stored.

Company discretion and resistance: Because administrative subpoenas don’t arrive with a judge’s signature, companies often have more room to negotiate, narrow, or refuse—especially if a request looks improper. The article describes withdrawals after litigation pressure, and Google saying it pushed back against an improper/overbroad subpoena.

Is this lawful? Is it constitutional?

1) First Amendment: anonymous speech and retaliation

If the underlying activity is (as described) documenting government activity, criticizing officials, protesting, or speaking anonymously, the strongest constitutional concern is the First Amendment.

Key issues:

Anonymous speech is protected. U.S. doctrine has long treated anonymity as part of speech and association rights, because it shields speakers from retaliation and social harm.

Chilling effect: Even without prosecution, forcing disclosure of identities can deter lawful speech—especially when the target is criticism of government.

Viewpoint discrimination / retaliation: If subpoenas are deployed because of criticism, that can look like unconstitutional retaliation—government punishing or burdening protected speech based on viewpoint.

The ACLU position quoted in the article (that recording and sharing such information and doing so anonymously is protected) fits squarely within this First Amendment frame.

Bottom line: If administrative subpoenas are being used primarily to intimidate and unmask critics absent evidence of a crime, the constitutional risk is substantial. Courts tend to be hostile to government tactics that function as “punish the speaker by exposing them.”

2) Fourth Amendment: reasonableness, scope, and the “metadata problem”

The Fourth Amendment prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures. The hard part is that U.S. law has historically been more permissive about the government obtaining third-party business records (the “third-party doctrine”), though modern cases have carved out meaningful limits for certain sensitive digital records.

Administrative subpoenas generally survive Fourth Amendment scrutiny when they are:

Issued within statutory authority

Relevant to a legitimate inquiry

Sufficiently specific

Not unduly burdensome

And there is some form of post-issuance judicial review available (i.e., the recipient can move to quash)

Where they get shaky is when they read like fishing expeditions (e.g., sweeping session logs, IP + physical address, linked IDs, and broad “any other identifiable information” requests) aimed at people the government already suspects did nothing illegal.

Bottom line: Even if “metadata” is easier to obtain than content, the more comprehensive the request—and the less tied to an actual predicate offense—the easier it is to argue it’s unreasonable or outside the permissible subpoena model.

3) Due process and separation-of-powers concerns (judge-free compulsion)

A constitutional tension sits underneath all of this: executive-branch compulsion without prior judicial authorization. Administrative subpoenas can be constitutional, but the legitimacy depends on guardrails:

clear statutory basis

realistic ability to challenge

meaningful judicial oversight when contested

non-abusive purpose

If used as a political tool, the whole structure looks less like routine regulation and more like executive power turned inward against dissent—and that’s when courts become far more receptive to constitutional challenges.

4) “Constitutional for whom?” — users abroad

If you’re abroad using U.S. platforms, the constitutional story gets messier:

U.S. constitutional protections are strongest for people in the U.S. and for proceedings in U.S. courts.

Non-U.S. persons located abroad often face weaker constitutional standing in certain contexts, even if the data is held by a U.S. company.

Practically, however, the platform is still in U.S. jurisdiction, so U.S. process can reach your data—regardless of where you live.

So: your vulnerability can increase abroad, while your ability to claim constitutional remedies can decrease—especially if you’re not a U.S. person and have limited access to U.S. courts or advocacy groups.

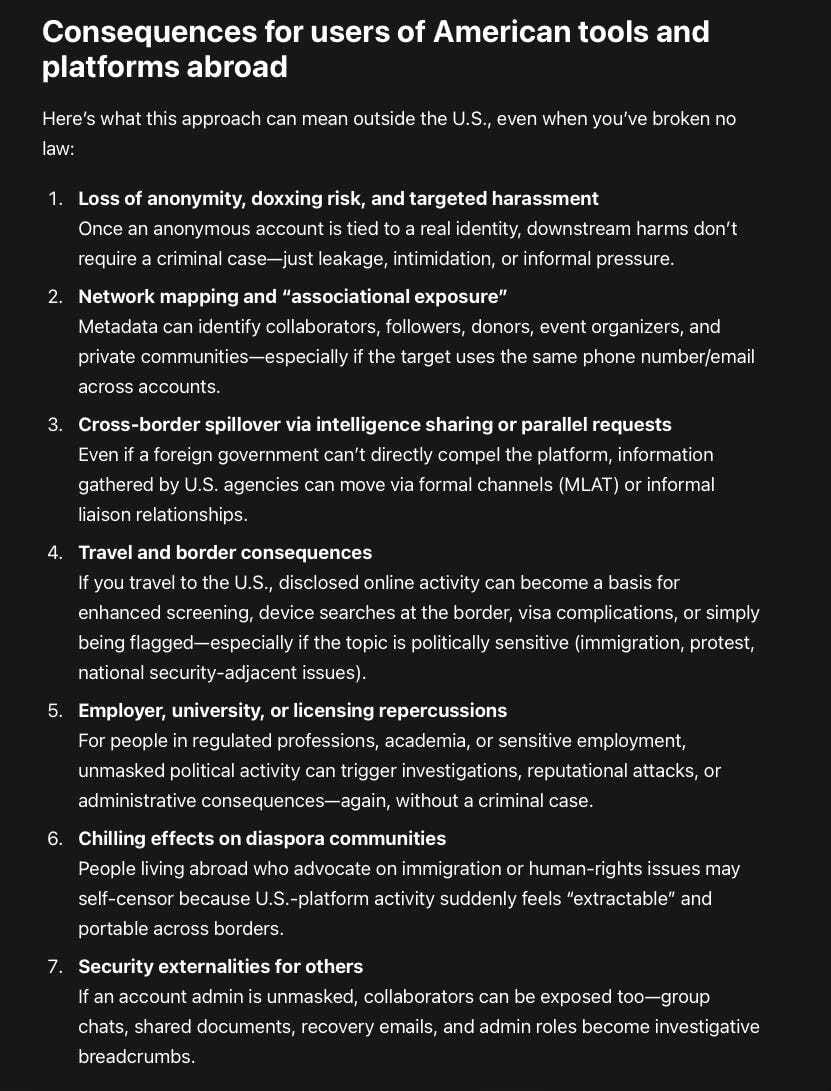

Consequences for users of American tools and platforms abroad

Here’s what this approach can mean outside the U.S., even when you’ve broken no law:

Loss of anonymity, doxxing risk, and targeted harassment

Once an anonymous account is tied to a real identity, downstream harms don’t require a criminal case—just leakage, intimidation, or informal pressure.Network mapping and “associational exposure”

Metadata can identify collaborators, followers, donors, event organizers, and private communities—especially if the target uses the same phone number/email across accounts.Cross-border spillover via intelligence sharing or parallel requests

Even if a foreign government can’t directly compel the platform, information gathered by U.S. agencies can move via formal channels (MLAT) or informal liaison relationships.Travel and border consequences

If you travel to the U.S., disclosed online activity can become a basis for enhanced screening, device searches at the border, visa complications, or simply being flagged—especially if the topic is politically sensitive (immigration, protest, national security-adjacent issues).Employer, university, or licensing repercussions

For people in regulated professions, academia, or sensitive employment, unmasked political activity can trigger investigations, reputational attacks, or administrative consequences—again, without a criminal case.Chilling effects on diaspora communities

People living abroad who advocate on immigration or human-rights issues may self-censor because U.S.-platform activity suddenly feels “extractable” and portable across borders.Security externalities for others

If an account admin is unmasked, collaborators can be exposed too—group chats, shared documents, recovery emails, and admin roles become investigative breadcrumbs.

Is it “lawful” in practice? Often the fight is procedural, not philosophical

One detail in the article is crucial: these subpoenas were reportedly withdrawn in several instances after litigation pressure, and at least one company said it pushed back.

That suggests the edge of legality may be exactly where this is operating: subpoenas that can be issued easily, but may not survive sustained scrutiny.

In real life, the constitutionality of an administrative subpoena campaign often turns on:

whether there is a credible investigative predicate

whether the demands are narrowly tailored

whether the government can articulate a lawful purpose that is not “identify critics”

and whether recipients (companies) and targets (users) can force judicial review

Recommendations: how people abroad can protect themselves

A. Reduce linkability (compartmentalize identity)

Use separate emails (aliases) and separate phone numbers (or none) for activist/political accounts.

Don’t reuse usernames, profile pics, recovery emails, or “about me” patterns across accounts.

Avoid linking payment methods, app store accounts, or government IDs to accounts used for sensitive speech whenever possible.

B. Prefer tools that minimize retained metadata

Use end-to-end encrypted messaging where the provider keeps minimal logs (the article cites Signal’s posture of collecting very little and therefore being unable to produce what it doesn’t have).

Homeland Security is trying to …

Treat mainstream social platforms as public broadcast systems from a metadata perspective: even if content is visible, the identity graph is the real prize.

C. Harden your accounts against “secondary capture”

Even when the subpoena is aimed at metadata, many unmaskings happen through:

account recovery channels

old devices

stale sessions

address books and synced contacts

cloud backups

Protective steps:

Turn on strong 2FA (ideally security keys) for your primary email and any accounts that control other accounts.

Audit recovery email/phone settings.

Regularly remove unused sessions/devices.

D. Assume “metadata is content” for threat modeling

If your safety depends on anonymity, behave as if:

IP + device + login times can reconstruct where you were

a “harmless” secondary Google account can still tie back to your real identity

contacts and DMs on non-E2EE platforms are discoverable via the social graph

E. Choose jurisdiction and architecture deliberately

For sensitive work, consider non-U.S. providers with strong privacy regimes and clear resistance policies.

Consider self-hosted or federated options for community coordination where practical (with realistic operational security; self-hosting is not automatically safer unless managed well).

F. Build a response plan (because prevention won’t be perfect)

Know which legal aid orgs can help quickly (in the U.S., groups like American Civil Liberties Union were involved in the example).

Homeland Security is trying to …

Keep minimal records that could endanger others if seized.

Maintain secure off-platform ways to alert your community if an account is compromised or unmasked.

G. Push platforms to act like adversaries of overreach, not silent data brokers

For civil society and institutions (universities, NGOs, publishers, advocacy groups):

Prefer services with transparency reporting, narrow compliance policies, and strong user notice.

Pressure vendors to commit contractually to: notice, narrowing, minimum disclosure, legal challenge, and public transparency where lawful.

Closing view

What the reporting depicts is best understood as a governance shift: moving from content moderation fights (visible) to identity extraction (often invisible). Administrative subpoenas can be legitimate tools, but when pointed at lawful dissent they start to resemble a state “unmasking” capability—one that can chill speech without ever winning a case in court.

For users abroad, the core risk is asymmetry: U.S. process can reach your data through U.S. platforms, while your practical ability to contest or remedy the harm may be limited. The most reliable protection is therefore architectural and behavioral: reduce linkability, minimize metadata, use services designed to retain less, and treat mainstream platforms as convenient—but structurally unsafe—places for high-sensitivity political activity.