- Pascal's Chatbot Q&As

- Posts

- ABP’s Palantir position—whether you see it as prudent exposure to a booming defense-tech contractor or as morally compromised capital—crystallizes the same global dilemma:

ABP’s Palantir position—whether you see it as prudent exposure to a booming defense-tech contractor or as morally compromised capital—crystallizes the same global dilemma:

retirement security is increasingly financed through technologies that make states more capable of surveillance, coercion, and kinetic harm.

“Your Pension Bought the Algorithm”: When Retirement Money Funds the Machinery of Surveillance and War

by ChatGPT-5.2

In January 2026, Dutch investigative outlet Follow the Money reported that ABP—the Netherlands’ largest pension fund for government and education workers—built a very large position in Palantir Technologies: about €635 million by end-June 2025, rising to roughly €825 million by end-September 2025.

The reporting frames this as more than a routine “tech allocation.” It is an investment in a company whose tools are widely associated—by critics, NGOs, and even some institutional investors—withhard-edged state power: military targeting, intelligence fusion, predictive policing, and immigration enforcement.

That raises a question that is uncomfortable precisely because it is universal: what happens when pension capital becomes a quiet, compounding co-investor in systems plausibly linked to human rights harms? The ABP-Palantir episode is Dutch in its immediate details, but the moral, ethical, and legal issues it surfaces travel extremely well—across borders, regulatory regimes, and asset classes.

1) The moral problem: “returns” that may be downstream of harm

At the center of the story is a basic moral tension: pension funds exist to secure dignified retirements, yet they invest in markets where profitability can be amplified by conflict, coercion, secrecy, and fear.

Follow the Money describes Palantir as repeatedly linked to allegations of human rights violations, specifically through its work with:

US immigration enforcement (ICE)—including reporting that Palantir is developing tools that map and score deportation targets and support “on-the-ground” operations.

Pensioenfonds ABP investeert ho…

Israeli military cooperation—with critics and some investors arguing Palantir products support surveillance of Palestinians and may be connected (directly or indirectly) to targeting practices in Gaza.

Pensioenfonds ABP investeert ho…

Even if you set aside contested claims and focus only on the type of capability—mass data fusion, person-level risk scoring, target generation—these are tools that increase the “efficiency” of state force. The moral question for a pension fund is not “is Palantir legal?” but: is it acceptable for mandatory worker contributions to be deployed into business models whose signature value proposition is operationalizing coercive power?

This becomes sharper because pension participants are typically captive investors: they cannot easily opt out, and they often have limited influence over holdings. The article reports participant pushback and feelings of powerlessness when funds refuse to explain specific decisions.

2) The ethical problem: due diligence that can’t be hand-waved away

ABP reportedly says it follows the OECD Guidelines and UN human rights frameworks, while declining to discuss specific companies.

That’s a standard institutional posture—but it collides with how modern “responsible investment” expectations actually work.

Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), companies (and by extension, financial actors) are expected to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for human rights impacts connected to their business relationships. The OECD framework goes further in spelling out how due diligence is meant to be operationalized for investors, including through portfolio-level processes and escalation where harms are severe.

The Follow the Money reporting highlights a practical red flag: there is no clear evidence ABP engaged Palantir (or at least no transparency showing that it did), despite the predictable and widely documented controversy around the company.

From an ethics standpoint, “we follow the OECD” is not a shield if the fund cannot show:

what risks it identified,

what it asked the company,

what it demanded as mitigation,

what it would do if mitigation fails,

and what it disclosed to beneficiaries.

This is not unique to ABP. Any large pension fund—Canadian, Australian, British, American, Japanese, Singaporean—faces the same ethical trap: ESG language without auditable process becomes reputation management, not responsibility.

3) The legal risk: complicity, disclosure, and “investment” as a business relationship

The legal issues here exist on three levels:

A) Human rights due diligence expectations (hardening into law)

In Europe, the direction of travel has been toward mandatory due diligence regimes. The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) entered into force in July 2024, aiming to require in-scope companies to identify and address adverse human rights and environmental impacts across value chains. (Implementation timelines and thresholds have been politically contested and subject to delay/rollback proposals, but the compliance trajectory remains real and compliance expectations are increasingly baked into procurement, financing, and litigation strategy.)

Even where a pension fund is not directly “in scope,” it operates in an ecosystem where banks, asset managers, index providers, and portfolio companies increasingly are.

B) OECD/UNGP-based complaints and liability theories

OECD Guidelines are not “law” in the classic sense, but they create accountability mechanisms through National Contact Points and form part of the reference architecture for what “reasonable” investor conduct looks like.

Separately, complicity risk is not theoretical. The UN Special Rapporteur report “From economy of occupation to economy of genocide” accuses a range of firms and financial actors of enabling serious harms connected to the Gaza conflict (allegations that are disputed, but influential). Once such claims are in circulation, investors face escalating exposure: civil society campaigns, exclusion lists, procurement restrictions, litigation experiments, and—most importantly—a rising evidentiary burden to show they did not knowingly finance or facilitate harm.

C) Disclosure and “greenwashing” / misrepresentation risk

In the EU, sustainable finance disclosure regimes (SFDR and related rules) push investors to be explicit about adverse impacts and sustainability claims, which increases legal exposure if practice doesn’t match marketing. Even outside Europe, the same pattern emerges through consumer protection rules, fiduciary litigation, and regulatory enforcement: if a fund claims “responsible investment,” it must be able to prove process integrity.

4) How “Dutch” is this problem? (Answer: not very.)

ABP is a Dutch pension fund, operating under Dutch and EU rules and public expectations. But the underlying issues generalize:

Pension funds globally pool capital at enormous scale and frequently invest via the same channels (US equities, tech indices, external managers, factor products). If Palantir is in major indices or widely held mandates, exposure becomes “default,” unless actively screened.

Reputational contagion is global. A controversy around an investee’s role in immigration raids or wartime targeting does not stay national; it moves through NGOs, the press, and social media in days.

Human-rights-linked finance expectations are globalizing. OECD and UNGP norms are routinely used worldwide even where not legally binding, and the OECD explicitly provides investor-oriented due diligence guidance.

Domestic politics can pull in opposite directions. The US is a good example: ERISA fiduciary law permits considering ESG factors when they are financially relevant, but the political and regulatory environment around ESG can swing sharply. That volatility itself is a risk factor for global funds holding politically sensitive contractors.

So while the ABP story is anchored in Dutch institutions and Dutch participants, it is fundamentally about how universal retirement systems interact with universal surveillance and conflict technologies.

5) What “responsible investors” elsewhere have done—and why it matters

Follow the Money notes that other institutional investors divested or excluded Palantir over concerns linked to Israel/Palestinian surveillance and broader human-rights risk, including Norway’s Storebrand.

This matters because it undermines the idea that “there was no reasonable alternative.” In other words: peers have judged the risk manageable only by exit, or at least by exclusion until stronger assurances exist. That puts pressure on any fund that stays invested to articulate why its due diligence reached the opposite conclusion.

Recommendations

For pension funds and long-term institutional investors worldwide

Treat “state power tech” as a distinct high-risk category.

Create a specific policy bucket for companies whose core products enable surveillance, targeting, predictive policing, detention, or deportation. Generic ESG scoring is not fit for purpose here.Run human rights due diligence like a safety case, not a brand exercise.

Borrow from engineering assurance: identify credible harm pathways, set mitigation requirements, define “stop conditions,” document decisions, and publish a beneficiary-readable summary. Align explicitly to UNGPs and OECD investor guidance.Engagement must be provable—or it’s not engagement.

If you claim engagement, disclose: questions asked, timelines, deliverables demanded, and escalation steps. If confidentiality limits details, disclose at least the structure and outcomes.Adopt a “conflict-zone enhanced due diligence” trigger.

If credible allegations link an investee to conflict-zone operations or severe rights impacts, automatically require board-level review and enhanced transparency.Offer beneficiary agency where possible.

Even small design changes (opt-out funds, “ethical sleeve” options, advisory votes, enhanced reporting) reduce the captive-investor legitimacy gap highlighted in the ABP reporting.Pensioenfonds ABP investeert ho…

Don’t hide behind “index exposure.”

If a holding is index-driven, say so—and decide whether to (a) accept it, (b) tilt away, or (c) create exclusions. “Passive” is not “non-responsible.”Stress-test political/regulatory volatility.

Where an investee is entangled with contentious government programs, model scenarios: sanctions risk, contract shock, lawsuits, procurement bans, and reputational drawdowns.

For regulators and supervisors (to the extent relevant worldwide)

Require “high-severity sector” disclosure.

Mandate specific reporting for investments in surveillance/targeting/immigration-enforcement tech: exposure, due diligence steps, and escalation outcomes.Clarify fiduciary duty in the context of severe human rights risk.

Make explicit that fiduciary duty includes managing long-term legal, reputational, and systemic risk—not just quarterly returns—consistent with prudent risk management principles.Create enforcement hooks against misleading ESG claims.

If funds market “responsible” products while holding high-risk companies without enhanced due diligence, treat that as potential misrepresentation.Support safe harbour for transparent engagement and escalation.

Funds are often reluctant to disclose. Regulators can enable standardized reporting templates that protect legitimate confidentiality while still giving beneficiaries meaningful accountability.Strengthen cross-border coherence.

Because capital is global, national regulators should align expectations around investor due diligence using OECD/UNGP frameworks to avoid a race to the bottom.

Bottom line

ABP’s Palantir position—whether you see it as prudent exposure to a booming defense-tech contractor or as morally compromised capital—crystallizes the same global dilemma: retirement security is increasingly financed through technologies that make states more capable of surveillance, coercion, and kinetic harm.

Outside the Netherlands, the precise legal levers differ, but the core obligations don’t: know the risk to people, show your work, and be prepared to exit when harms are severe and unmitigated.

·

11 DECEMBER 2025

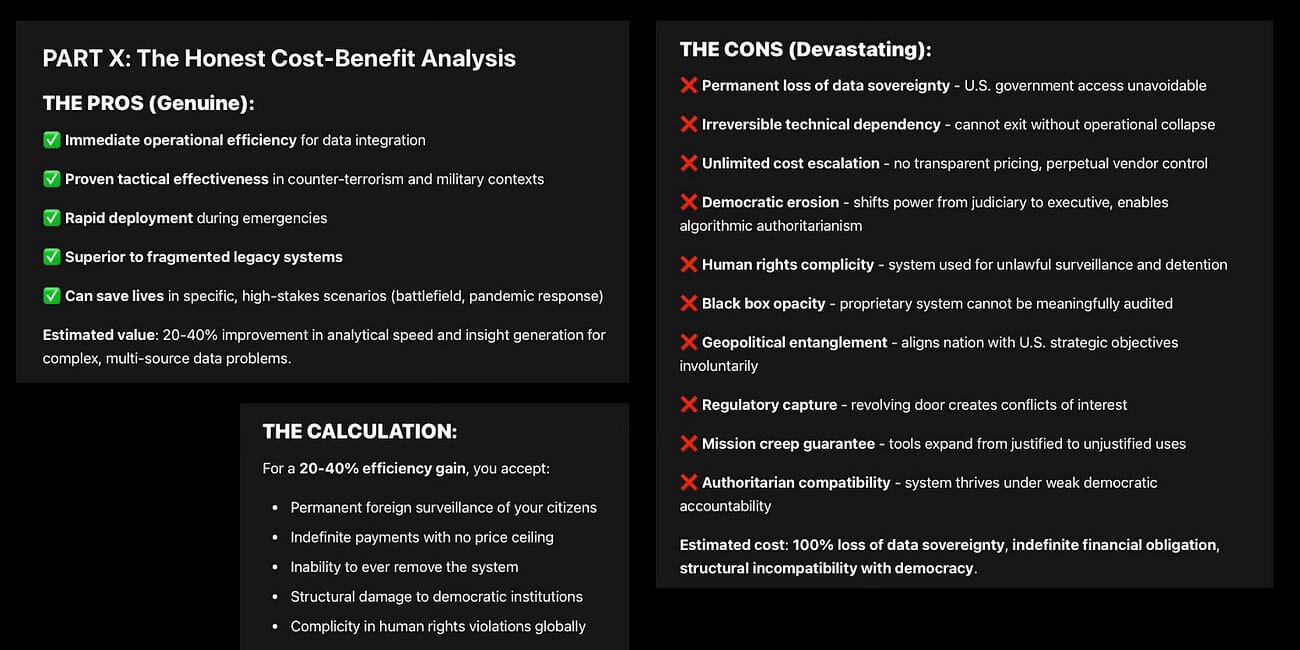

The Sovereignty Trap: Why Palantir Collaboration Is a Faustian Bargain for Democratic Nations

·

2 FEBRUARY 2025

Asking AI services: Tell me everything you know about Palantir Gotham, Europa and explain just how dependent Europe is on Palantir for its enforcement and intelligence work and analytics.

·

18 AUGUST 2025

Palantir’s Expanding Influence and the Global Democratic Dilemma

·

1 JULY 2025

Palantir – Total Surveillance or Security Guarantee?

·

2 FEBRUARY 2025

It's probably not the best basis for the US either. A LOT more disciplines, experts and scientists of many more fields are required. A tech heavy think-tank(er) is likely going to topple. But Karp does display a lot of masculinity though, with his strong talk! 🦾 🤖 💪 Clip:

·

19 APRIL 2025

·

11 AUGUST 2024

Asking AI services: Please read the article "Microsoft is partnering with Palantir to sell AI to US government agencies" and the post "Palantir and Microsoft Partner to Deliver Enhanced Analytics and AI Services to Classified Networks for Critical National Security Operations

·

8 MARCH 2025

Asking AI services: Please read the article “We found a DOGE guy at NASA because his Google Calendar was public” and explain whether this demonstrates that by using DOGE, the Trump Administration is effectively collaborating with the Deep State? How do you think the MAGA movement will feel about that?